Welcome to En-Gedi…

Featured Article: (from Exodus)

Featured Article: (from Exodus)

I Do This Because…

by Lois Tverberg

“For seven days eat bread made without yeast and on the seventh day hold a festival to the LORD. On that day tell your son, `I do this because of what the LORD did for me when I came out of Egypt.’ This observance will be for you like a sign on your hand and a reminder on your forehead that the law of the LORD is to be on your lips. For the LORD brought you out of Egypt with his mighty hand.” (Exodus 13:6, 8-9)

In Exodus 13, God told the Israelites to celebrate the Feast of Unleavened Bread every year in order to remember that the Lord brought them out of Egypt. They were to explain that the reason why they did it was because God redeemed them. By performing this ceremony each year, they would be continually mindful and grateful that God had redeemed them, and would teach their children about God’s love for them.

Interestingly, many of the laws of the Torah are rooted in the redemption from Egypt. Out of gratitude and obligation, when the Israelites realized what God had done for them, they should feel compelled to live differently:

Do not profane my holy name. I must be acknowledged as holy by the Israelites. I am

the LORD, who makes you holy and who brought you out of Egypt to be your God. I am

the LORD. (Lev. 22:31, 33)If one of your countrymen becomes poor and is unable to support himself among you, help him so he can continue to live among you. I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of Egypt to give you the land of Canaan and to be your God. (Lev. 25:35, 38)

If one of your countrymen becomes poor among you and sells himself to you, do not make him work as a slave. Because the Israelites are my servants, whom I brought out of Egypt, they must not be sold as slaves. (Lev. 25:39, 42)

Each of the laws above is directly linked to God’s action of bringing the Israelites out of Egypt. They should help the poor live in the land because God gave them the land to live in. They shouldn’t hold other Israelites as slaves because God brought them out of slavery. Many other regulations are linked either directly or indirectly back to this act of God on their behalf.

Christians can learn a valuable lesson from this. When we think of our redemption in Christ and the price that he paid for us, it should compel us to live differently. We should forgive others, because he forgave us. We should humbly serve others, because Jesus humbled himself out of love to die for our sins. If we continually remind ourselves of how we’ve been loved, we will love others in the same way.

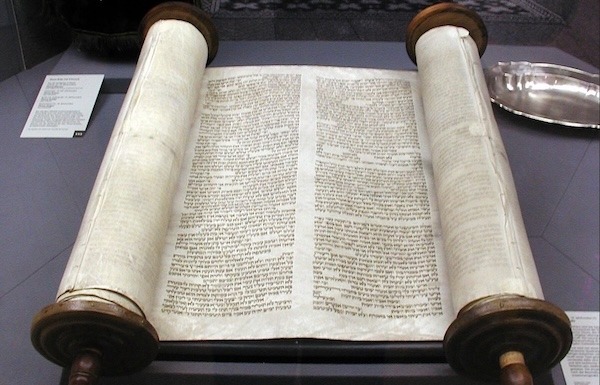

Photo: Willy Horsch

We’re pleased to be able to share this difficult-to-find classic by Brad Young. Check it out!

The Jewish Background to the Lord's Prayer

by Brad H. Young

© 1984, Gospel Research Foundation Inc.

Softcover, 46 pages, $8.99

- Explore the Jewish roots of the Lord's Prayer

- Learn how the Dead Sea Scrolls, rabbinic literature, Jewish prayers, and worship breathe fresh meaning into the revered words of the Lord's Prayer

- Understand Jesus' powerful prayer better in the light of Jewish faith and practice

Dr. Brad H. Young (PhD Hebrew University, under David Flusser) is the founder and president of the Gospel Research Foundation in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He is emeritus professor of Biblical Literature in Judaic-Christian Studies in the Graduate School of Theology at Oral Roberts University. Young has taught advanced language and translation courses as well as the Jewish foundations of early Christianity to graduate students for over thirty years.

Check out what else is available from the En-Gedi Resource Center bookstore too...