by Lois Tverberg

In Leviticus, we read an intriguing law that God gave Israel about observing a year of Jubilee:

‘You are also to count off seven sabbaths of years for yourself, seven times seven years, so that you have the time of the seven sabbaths of years, namely, forty-nine years. ‘You shall then sound a ram’s horn abroad on the tenth day of the seventh month; on the day of atonement you shall sound a horn all through your land. ‘You shall thus consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim a release through the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you, and each of you shall return to his own property, and each of you shall return to his family. ‘You shall have the fiftieth year as a jubilee; you shall not sow, nor reap its aftergrowth, nor gather in from its untrimmed vines. (Lev 25:8 – 11)

God proclaimed that every seventh year was to be a sabbath for the land: crops were not to be planted, and they were to live on what God had provided before that time and what grew up by itself.

After seven sabbath years came a year of Jubilee, which along with being a Sabbath for the land, also was a “year of release.” This meant that all Israelites who were in bondage were freed, and anyone who had sold his ancestral property would receive it back, and all debts were forgiven. The word “Jubilee” comes from the word Yovel, a Hebrew word for the ram’s horn that was used to proclaim the year.

After seven sabbath years came a year of Jubilee, which along with being a Sabbath for the land, also was a “year of release.” This meant that all Israelites who were in bondage were freed, and anyone who had sold his ancestral property would receive it back, and all debts were forgiven. The word “Jubilee” comes from the word Yovel, a Hebrew word for the ram’s horn that was used to proclaim the year.

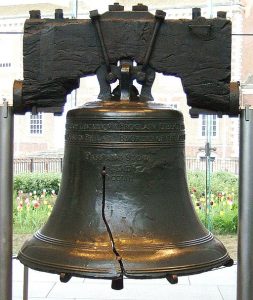

Another name for it was a “year of release (deror).” The Hebrew word deror means “release” or “liberty.” Early Americans, who knew their Bibles better than we do, placed Leviticus 25:10 on the Liberty Bell: “Proclaim LIBERTY throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants thereof.”

Our founding fathers found inspiration in the year of Jubilee as they were establishing the United States. What did they find so special about this concept?

The Purpose of the Year of Jubilee

As part of God’s covenant with Israel, he promised to give the Israelites the land of Canaan. After the conquest of the land, it was divided among the tribes so that each family had its own share. In the ancient world, owning land was greatly prized because it was a source of food, income and security.

In that economy where people depended on the crops they raised, if a family had a bad harvest and ran out of food, they were forced to go into debt or even sell their land. If they couldn’t recover but fell further behind, they would have to sell themselves into slavery or leave the country, like Naomi and Elimelech in the book of Ruth.

In that economy where people depended on the crops they raised, if a family had a bad harvest and ran out of food, they were forced to go into debt or even sell their land. If they couldn’t recover but fell further behind, they would have to sell themselves into slavery or leave the country, like Naomi and Elimelech in the book of Ruth.

People did not borrow money and sell land for business purposes, they did it only out of desperate economic need. So the Jubilee was for one main purpose — to provide for the poor who had gone into debt or lost their land, so that they would be able to start over again. Without it, the wealthy would always do better in bad years, and the land would tend to move into their hands while those who had lost their land would become permanently enslaved.

Another effect of the Jubilee would be to stop the destruction of families. If a man lost his land and sold himself and his family into slavery, or if he moved out of the country, he would likely never see his family together again. Part of the reason Naomi was distraught was because not only had she lost her hope for future descendants, but by leaving Israel, she also lost her family and past. When she returned, she was reunited with her family.

The year of Jubilee was to be a year that people returned home and families were brought together again.

The evidence suggests that Israel never observed the year of Jubilee. In 2 Chronicles it reports that they never allowed the land to have its Sabbath every seventh year, and if they never did that, they most likely never observed the year of Jubilee either. Several of the prophets lament the exploitation of the poor by the rich, which also hints that they never observed a Jubilee year.

There is, however, evidence from other Middle Eastern countries that years of release were proclaimed in ancient times when a new king came into power. It would be a way to ensure support from the masses when a king would declare all debts void and set free all those in bondage to debt.

It is interesting that the prophets thought of this association of a year of Jubilee with the coming of the Messiah. The primary image of the Messiah was that he would be a king like David, so just as the new kings of other countries declared a Jubilee when they came into power, the Messianic king would as well. Isaiah says:

The Spirit of the Sovereign LORD is on me,

because the LORD has anointed me

to preach good news to the poor.

He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted,

to proclaim freedom for the captives

and release from darkness for the prisoners,

to proclaim the year of the LORD’s favor. (Is 61:1-2)

This is a picture of the coming messianic King, right after he is anointed by God, declaring good news of the jubilee year. Each phrase is about how great the “year of the Lord’s favor” will be to those who have been imprisoned or enslaved because of their debt. The king will let them go home and start life over, to their great joy.

Jesus and the Year of Jubilee

In Luke 4, at the beginning of his ministry, Jesus reads the passage from Isaiah 61 in the synagogue in his hometown, and he says “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing!” his audience would have heard this as an obvious claim to be the Messiah who has now come into power.

Throughout Jesus’ ministry he uses images from the year of Jubilee, but he takes the image of the poor person set free from debt, and uses debt as a metaphor of sin. For instance, when the sinful woman comes and washes his feet with her tears and Simon, his host, wonders if he knows what a sinner she is, he tells the parable:

Two men owed money to a certain moneylender. One owed him five hundred denarii, and the other fifty. Neither of them had the money to pay him back, so he canceled the debts of both. Now which of them will love him more?” Simon replied, “I suppose the one who had the bigger debt canceled.” “You have judged correctly,” Jesus said. (Luke 7:41-43)

The poor who are set free in the Messianic kingdom are the poor in spirit, those who know they are in debt to God because of their sin. So the “good news of the kingdom of God” is that the Messianic King has come, and has declared complete forgiveness of debt — sin —for those who will repent and enter his kingdom. It is good news to the poor rather than to the rich who don’t see that they need to be forgiven.

We see in Jesus’ use of the picture of the Jubilee the greatest picture of God’s grace through Christ. Those in prison are those who are under a crushing debt they could never repay. We see Jesus, the new king, setting prisoners free of debt that they owe because of their sin. Through Jesus’ work on the cross, those who become a part of his Kingdom receive a forgiveness of a debt they cannot repay themselves so that they can start over as new person.

~~~~

Photos: Tony the Misfit on Flickr [CC BY 2.0], Nitin Bhosale on Unsplash, Peter Paul Rubens [Public domain]