Back when I was in college, I took part in a performance of Handel’s Messiah. Having grown up in a Christian home that mostly only read the Gospels and Paul, I was puzzled by the haunting lyrics of one chorus. It sounded like it was straight out of the New Testament, but I had never heard it before. I was moved to tears by each line:

Back when I was in college, I took part in a performance of Handel’s Messiah. Having grown up in a Christian home that mostly only read the Gospels and Paul, I was puzzled by the haunting lyrics of one chorus. It sounded like it was straight out of the New Testament, but I had never heard it before. I was moved to tears by each line:

Surely, surely, He hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows.

He was wounded was for our transgressions,

He was bruised for our iniquities;

the chastisement of our peace was upon Him.

These lines obviously describe Christ’s suffering and atonement of our sins, but where did they come from? Puzzled, I searched my Bible. Even now I remember my shock when I learned that these lines were not the work of a New Testament writer, but were from the book of Isaiah, chapter 53:

Surely he took up our infirmities and carried our sorrows, yet we considered him stricken by God, smitten by him, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we are healed.

We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to his own way; and the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed and afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth; he was led like a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth.

By oppression and judgment he was taken away. And who can speak of his descendants? For he was cut off from the land of the living; for the transgression of my people he was stricken. He was assigned a grave with the wicked, and with the rich in his death, though he had done no violence, nor was any deceit in his mouth.

Yet it was the LORD’s will to crush him and cause him to suffer, and though the LORD makes his life a guilt offering, he will see his offspring and prolong his days, and the will of the LORD will prosper in his hand. After the suffering of his soul, he will see the light [of life] and be satisfied; by his knowledge my righteous servant will justify many, and he will bear their iniquities. (Isaiah 53:3-11, NIV 1984)

Reading this passage, we can hear its clear and obvious message about Christ. It is so detailed and pointed in its description of Jesus’ death and resurrection that it seems to be a restatement of the basic tenets of the gospel message for the early church.

In fact, it was written almost 700 years before the birth of Christ! I found this a most amazing discovery — that the prophecy about Jesus’ mission on earth could be so clearly laid out, so many centuries before he was born. The New Testament writers refer to it many times, seeing that it so clearly foretold Jesus’ mission on earth.

Yet a More Amazing Discovery

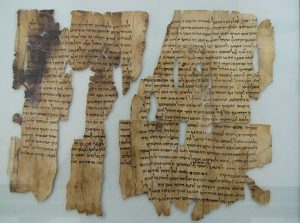

For many years, I was quite thrilled at my Bible study discovery. If I had known my Old Testament better, maybe it would not have been that special. Then I began to learn more about archeology and the discovery of the the Dead Sea Scrolls. In 1948, many ancient scrolls and fragments were uncovered in the Essene community of Qumran, in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea in Israel.

For many years, I was quite thrilled at my Bible study discovery. If I had known my Old Testament better, maybe it would not have been that special. Then I began to learn more about archeology and the discovery of the the Dead Sea Scrolls. In 1948, many ancient scrolls and fragments were uncovered in the Essene community of Qumran, in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea in Israel.

Before that discovery of the Qumran scrolls, the oldest known manuscripts of the Old Testament were from about 900 AD. Skeptics had charged that modern Bibles were full of legends inserted by pious believers. They were silenced by the finding of the Dead Sea documents, which were a thousand years older than any other manuscript they had found, from about 100 BC.

Of all the momentous discoveries at Qumran, that one that made scholars’ jaws drop was the “Great Isaiah Scroll,” which contained a complete manuscript of the book of Isaiah. Copies of almost all of the books of the Old Testament had been found, but they were in fragments that needed to be pieced back together. Just a few scrolls were found intact, including two copies of the book of Isaiah. Both the original text of Isaiah and the copy on this scroll predate the birth of Jesus.

The text of Isaiah 53 in this scroll was virtually identical to manuscripts of over a thousand years later, even though it had been hand-copied over and over again. The words I quoted above are actually in the text found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The only difference between that text and later copies is the small insertion in brackets, [of life]. The fact that so little change was seen over thousands of years shows the enormous reverence the scribes had for the text.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls was tremendously affirming to Christians and Jews who wondered if the biblical text had been accurately preserved. But finding the Isaiah Scroll, and even a copy of Isaiah’s powerful prophecy in chapter 53 that existed a hundred years before Christ is to me the most amazing discovery of all.

~~~~

Photos: Mark Kamin [CC BY-SA 2.5], Ken and Nyetta [CC BY 2.0]