by Lois Tverberg

For I say to you that unless your righteousness surpasses [goes beyond] that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven…You have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.” But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven;…You are to be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect. Matthew 5:20, 43-45, 48

Jesus gives one of his most challenging teachings in the Sermon on the Mount. He frames it at both the beginning and the end with an exhortation to perfection. He says that those who do and teach others to do even the least of God’s commands will be called “great” in his kingdom. And then he says that “unless your righteousness surpasses that of the scribes and Pharisees” you are not a part of God’s kingdom. He continues by stating several rulings about divorce, anger and lust that each go beyond the laws of the day, and then ends with words about aiming to be perfect, like God himself.

Jesus gives one of his most challenging teachings in the Sermon on the Mount. He frames it at both the beginning and the end with an exhortation to perfection. He says that those who do and teach others to do even the least of God’s commands will be called “great” in his kingdom. And then he says that “unless your righteousness surpasses that of the scribes and Pharisees” you are not a part of God’s kingdom. He continues by stating several rulings about divorce, anger and lust that each go beyond the laws of the day, and then ends with words about aiming to be perfect, like God himself.

Many people read this passage as saying that these are the qualifications for earning your way to heaven, and an extremely tough list of rules to follow. It’s easy to be overwhelmed by this interpretation.

It’s important to understand that the phrase “enter the kingdom of heaven” is idiomatic, not meaning “go to heaven when you die.” It means to be a part of God’s redemptive reign on earth right now—to live with God on the throne of your life and do his will. Rabbis from Jesus’ day used the phrase “kingdom of heaven” frequently in this way, and his Jewish context allows us to unlock this passage. Jesus is describing how to do God’s will, not how to earn your way to heaven. Our salvation is based on Jesus’ atonement for our sins and the trust we place in him, not that we “earn our way.”

Another thing that can help us understand this passage is insight on the difficult line: “unless your righteousness surpasses that of the scribes and Pharisees.” The verse sounds competitive – as if we are trying to beat certain people in their strict observance of regulations. But it’s likely that the idea of the phrase about “surpassing the scribes and Pharisees” is not about them as people, but about them as interpreters of the law. The passage isn’t about outperforming them in one’s stringent piety, but about seeking to do God’s will beyond the official interpretation of the law.

The word that we translate “surpass” is from the Greek word “perissos”, meaning “to abound, overflow, exceed.” One translation says “Unless your righteousness goes beyond that of the experts in the law…” (NET Bible).

We can interpret this line as, “do more than what the finest interpreters of the law say that you must do.” Then it fits the rest of the passage where Jesus points out various minimums set in the law, and instructs his disciples to go beyond that. The law says “don’t kill” but you should try not to even stay angry. The law says, “don’t commit adultery” but you should even avoid lust. Not only should you not seek revenge against your enemies, you should find ways to show them the love of God. Loan them money, carry their burdens. Anything.

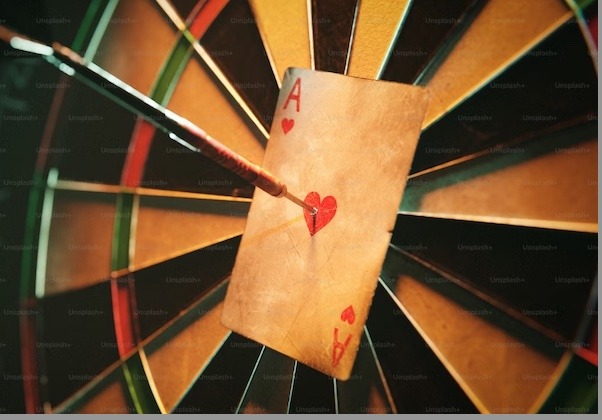

This whole passage is not so much about a list of toughened rules, but about encouraging us to change where our aim is. It is easy to look for what is the minimum so that you can just do that. But in every case Jesus is saying, “Don’t live by the minimum!” Don’t say to yourself, as long as I don’t commit adultery, it’s fine to lust. Don’t say that as long as I don’t kill someone, I can be furious with them. If you want to be a part of God’s redemptive kingdom on earth, don’t ask how little you can do, but ask how much you can do, to please your Father in heaven.

~~~~

To explore this topic more, see chapter 12, “Jesus and the Torah” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 163-179.

To explore this topic more, see chapter 12, “Jesus and the Torah” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 163-179.

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. Matthew 5:17-19

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. Matthew 5:17-19

Then, later, in Genesis 2, it says that God formed the man from the dust of the ground and then describes how woman was taken out of the first man. At first, these two creation accounts seem to be in disagreement – were both male and female created at the same time, as in 1:27, or was the man formed first and the woman later, as in chapter 2?

Then, later, in Genesis 2, it says that God formed the man from the dust of the ground and then describes how woman was taken out of the first man. At first, these two creation accounts seem to be in disagreement – were both male and female created at the same time, as in 1:27, or was the man formed first and the woman later, as in chapter 2?