by Bruce Okkema

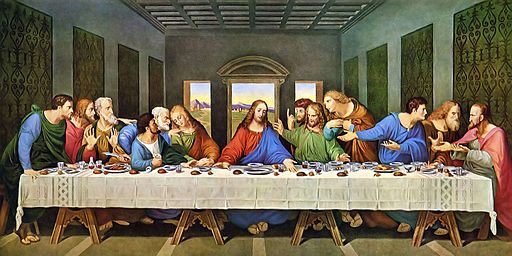

Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” has come to be one of the most famous paintings of all time, yet many do not know its original setting. The image has been reproduced countless times the world over, and has become the subject of many paintings itself.

Because this painting is so well known, it has been highly influential in establishing a picture in our minds of what the last night before Jesus’ death must have been like. Unfortunately it is the wrong picture! Nearly every detail in the picture is culturally inaccurate.

To list just a few: the people in the picture look European, certainly not Semitic. The supper that Jesus was participating in was a Jewish Passover Seder — Pesach in Hebrew. It was always celebrated after sundown, not with the blue sky as we see. These feasts have usually been celebrated with family, so there may have been other women and men dining with them, and children of all ages.

Jesus would have not been seated in the middle of a long table, he would have reclined on a couch or pillow on the floor, leaning on his left elbow. He certainly would not have been eating fish and leavened bread loaves! Rather, he would have been eating lamb, bitter herbs, and unleavened bread as was commanded in Exodus 12. To leave lamb off the menu for Passover is to forget an essential detail of the supper in which Jesus presents himself as the true lamb of Passover.1

At the point in the Seder when Jesus took the bread, broke it and said, “this is my body broken for you” (Luke 22:19), those present would have seen him hold up the unleavened bread, the “bread of affliction” that reminded them of God’s redemption from Egypt. It was free from leaven, representative of sin in this case, just as a pure sacrifice offered at the temple had to be free of leaven. Without that image, we miss the message in Jesus’ powerful words.

Does it matter that we have the wrong picture? It does if we want to understand Jesus — if we want to understand his culture. Our human mind always associates images with our thinking process; in one sense, we think in terms of pictures. If we use the wrong picture, we will likely miss the message, and the story will sound different than intended.

Da Vinci never intended for this painting to become the theological icon that it has become. The peculiar details that he incorporated into the painting (for example, 25 hands for 12 disciples) are the subject of many books, but it is certain that historical accuracy was not his objective.

Ironically, Da Vinci’s painting which has taken Jesus out of his context, has itself has been taken out of context. We usually see the image portrayed as if it were a painting on canvas, when actually it was a mural measuring 15’ x 29’ painted on a wall in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy.

Da Vinci was commissioned in 1494 by a patron of the town, Duke Ludovico, to paint a fresco in the monk’s dining hall there. Fresco is a technique using water-based paint applied directly to plaster while it is still wet, and requires the artist to work quickly before the plaster dries. Da Vinci simply could not paint this way; he wanted time to consider, to go back weeks, months, or even years later to add things.

Da Vinci was commissioned in 1494 by a patron of the town, Duke Ludovico, to paint a fresco in the monk’s dining hall there. Fresco is a technique using water-based paint applied directly to plaster while it is still wet, and requires the artist to work quickly before the plaster dries. Da Vinci simply could not paint this way; he wanted time to consider, to go back weeks, months, or even years later to add things.

So he decided to lay down a surface on the wall that would allow him to work as he usually did.2 He invented a technique of applying a mixture of oil and tempera over two layers of plaster, a technique that unfortunately proved to be unsuccessful. He could not have predicted that these materials would succumb to the attacks of pollution or humidity. Even during Leonardo’s lifetime the irreversible process of deterioration set in and pieces started flaking off the painting.3

The painting has undergone numerous restorations and remarkably survived a bombing raid in August of 1943, when a protective curtain hung over it prevented irreparable damage. Even so, the painting is just a shadow of what it originally was; its now dulling, neutral colors were once vivid and luminous.

The painting has undergone numerous restorations and remarkably survived a bombing raid in August of 1943, when a protective curtain hung over it prevented irreparable damage. Even so, the painting is just a shadow of what it originally was; its now dulling, neutral colors were once vivid and luminous.

As stated earlier, it was commissioned for a dining hall, but because we usually see the image cropped, we don’t realize that it was actually quite ingenious in its original setting.

Da Vinci made it look as though Jesus and his disciples were eating right there with the monks. The table at which the disciples sat was just like the ones the monks used, as were the dishes, the glassware, and even the tablecloth, with its blue embroidery and fringed ends. The architecture in the painting itself is an extension of the real architecture of the room in which it was painted. From the place occupied by the prior of the convent at meal-times, the painting appears as a continuation of the real refectory building, and the figure of Christ seems to offer the elements from the picture to the real spectators outside it. He chose to paint the moment when Jesus had just told his friends that one of them would soon betray him. The disciples were shown reacting in individual ways, with gestures and facial expressions that were very theatrical and full of emotion.4

Da Vinci’s intention was to present a character study, which is one of the reasons the painting took him four years to complete. The final work was preceded by a long series of preparatory drawings which are today in various collections around the world. The figures which gave Leonardo the greatest trouble were those of Christ and Judas, so much so that while the work was in progress, the prior of the convent went to the Ludovico, the Duke who had commissioned the work, to complain because they had not yet even been sketched.

“Perhaps the fathers know how to paint?” retorted Da Vinci to Ludovico. “How can they judge an artistic creation? For one whole year I have gone every day, morning and evening, to the Borghetto, where the scum of humanity live, to find a face that will express the villainy of Judas, and I have not yet found it. Perhaps I could take as a model the prior who has been complaining about me to your Excellency.”5

Understanding that Jesus was celebrating the Passover meal is critical for understanding how he fulfills its promises of redemption, and brings it to a new level in the lives of his followers. From the time Abraham told Isaac in Genesis 22:8 that “God himself will provide the lamb for the offering, my son” until now, the story of God’s redemption is the story that we have to get right.

Telling the story of how God himself redeemed his people out of Egypt, gave the covenant, and dwelled among them — all of this is commemorated during the Seder. It is vital to understanding Jesus and his ministry as the great fulfillment of that first act of redemption by God. The story is all about the sacrifice, the covenantal meal, blessing, teaching, and making disciples. This needs to be conveyed accurately in words and in pictures for those who come behind us to know the truth.

When you consider the impact that Da Vinci’s wrong picture has had in etching our picture of Jesus, intentionally or not, you can realize the seriousness of taking things out of context. Along with this, due to the innumerable “restorations” and re-paintings of Da Vinci’s work over 500 years, we cannot even be sure that what we see today is what he actually painted.

This scenario has been a great example of what we must not do with scripture. As we are learning and studying we should always be careful to keep things in their historical and cultural context. So as we listen, and dig, and teach, and paint, let us pray for much wisdom so that all those whom we disciple will hear a story, and see a picture that is bright, and clear, and true.

~~~~

1 Dwight A. Pryor, “Misconceptions about Jesus and the Passover” Series by the Center for Judaic-Christian Studies, Dayton, Ohio jcstudies.com

2 Diane Stanley, Leonardo Da Vinci, William Morrow & Company, New York, 1996

3 Francesca Romei, Leonardo Da Vinci, Peter Bedrick Books, New York, 1994

4 Diane Stanley, ibid

5 Liana Bortolon, The Life & Times of Leonardo, The Curtis Publishing Company, New York, 1997

Photos: Leonardo da Vinci [Public domain], Joyofmuseums [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], BB [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]