by Lois Tverberg

You have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

– Matthew 5:43-44

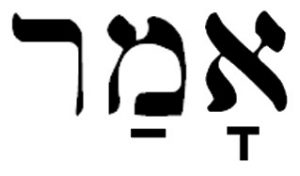

Many times Jesus uses the phrase “You have heard it said.” It is helpful to know that Jesus was using a rabbinic idiom in that phrase – the word “say,” amar, was used by the rabbis to mean “interpret” in terms of giving the proper interpretation of the scriptures as to how to apply its laws. Jesus often preceded his legal rulings with “You have heard it said” (meaning, others have interpreted God’s word to mean one thing) and “but I say unto you” (meaning, I interpret it differently, in the following way).

Many times Jesus uses the phrase “You have heard it said.” It is helpful to know that Jesus was using a rabbinic idiom in that phrase – the word “say,” amar, was used by the rabbis to mean “interpret” in terms of giving the proper interpretation of the scriptures as to how to apply its laws. Jesus often preceded his legal rulings with “You have heard it said” (meaning, others have interpreted God’s word to mean one thing) and “but I say unto you” (meaning, I interpret it differently, in the following way).

One verse that is clarified by knowing this is Matt 19:17 and its parallels in other Gospels:

And He said to him, “Why are you asking Me about what is good? There is only One who is good; but if you wish to enter into life, keep the commandments.” – Matt 19:17

Jesus responds to the man’s question about doing a good thing in order to earn eternal life with the phrase commonly translated as “Why do you call me good?” or “Why do you ask me about what is good?” The Greek there is awkward – the line is actually something more like “Why do you say (amar) ‘good'”? Meaning, why do you interpret “good” in the way that you do? He was objecting to the man’s idea that he could use a good deed as a bargaining tool, to earn his way to heaven. He tells the man to obey God’s law as he should, but that to have eternal life he needs to follow after him.1

It may surprise us that Jesus did not throw out God’s law, but instead brought it to its pinnacle in his teaching, showing that it was all built on the central commands to love God and to love your neighbor. Whenever we read any of God’s Word to find out how it applies to our lives, we need to read it through the eyes of Jesus and let his words be its final interpreter.

~~~~

See Listening to the Language of the Bible, by Lois Tverberg and Bruce Okkema, En-Gedi Resource Center, 2004. This is a collection of devotional essays that mediate on the meaning of biblical words and phrases in their original setting.

For a friendly, bite-sized Bible study of five flavorful Hebrew words, see 5 Hebrew Words that Every Christian Should Know, by Lois Tverberg, OurRabbiJesus.com, 2014 (ebook).