by Lois Tverberg

[The Kingdom of God] will be like a man going on a journey, who called his servants and entrusted his property to them. To one he gave five talents of money, to another two talents, and to another one talent, each according to his ability. Then he went on his journey. The man who had received the five talents went at once and put his money to work and gained five more. So also, the one with the two talents gained two more. But the man who had received the one talent went off, dug a hole in the ground and hid his master’s money. Matthew 25:14-18

We all struggle with our weaknesses, and for some of us, they are pretty profound. We might be plagued by a physical disability, mental illness, psychological problems, or a dysfunctional family background. Jesus’ describes people with different amounts of gifts in the parable above, and many of us feel like the servant who received one talent rather than five. It’s often true that people who struggle with limitations bury their talents and give up on serving God. We feel worthless, like only those who are great in human achievement are worthy of serving God. We may even believe that God is harsh and unfair, as the man in the parable viewed his employer.

The rabbis relay a similar parable with a wise message: A king hires two watchmen over his garden—one blind, and the other lame. The two watchmen decide to steal his fruit, but neither can do it alone. The lame man can’t reach the fruit, and the blind man can’t see where it is. So the blind man hoists the lame man on his shoulders, and together they pick the fruit! When the king discovers the crime, both of them claim they were incapable of stealing the fruit. So the king lifts the lame man on the blind man’s shoulders and judges them both as one. (B. Talmud, Sanhedrin 91a-b)

The point of this parable is that all of us have two aspects —our flesh, that may have disabilities or psychological problems; and our will—our desire to accomplish what we are called to do. Together they determine what we can do, and we can’t ignore our calling to serve God because of our struggles.

We may be tempted to give up and be the chronic “victim,” feeling cheated by a harsh God, having no obligation to help others. Instead, we should look for ways to use our difficulties to serve God. Dave Brownson was tormented for years with schizophrenia and manic depression. His disability made him feel worthless and sub-human, and that he had no calling in life. But then he began a ministry counseling others with serious mental illness, and supplied enormous comfort to people in circumstances similar to his own. It was through his illness that he gained the empathy and experience to reach out to this needy group of people. (1)

God knows the talents he has given you, and he knows that many struggle with enormous problems every day. When we finally stand before him, may we be counted among those who have multiplied what we have been given.

(1) Bill & Helen Brownson, Billy and Dave (Words of Hope, Credo House Pub., Grand Rapids, 2006).

Photo: Wagner T. Cassimiro “Aranha”

people to obey God’s word and stay far from sin. One technique they employed was to point out how seemingly small sins can evolve into much greater sins. (1) This was called kalah ka-hamurah (“light as heavy”), an abbreviation of mitsvah kalah ka-mitsvah hamurah (“a light commandment is like a heavy commandment”). In other words, kalah ka-hamurah relays the sense that breaking a less significant law is linked to breaking a greater law. The same style of logic appears in Jesus’ teaching when he compares anger to murder and lust to adultery (Mt 5:22-23, 27-28).

people to obey God’s word and stay far from sin. One technique they employed was to point out how seemingly small sins can evolve into much greater sins. (1) This was called kalah ka-hamurah (“light as heavy”), an abbreviation of mitsvah kalah ka-mitsvah hamurah (“a light commandment is like a heavy commandment”). In other words, kalah ka-hamurah relays the sense that breaking a less significant law is linked to breaking a greater law. The same style of logic appears in Jesus’ teaching when he compares anger to murder and lust to adultery (Mt 5:22-23, 27-28).

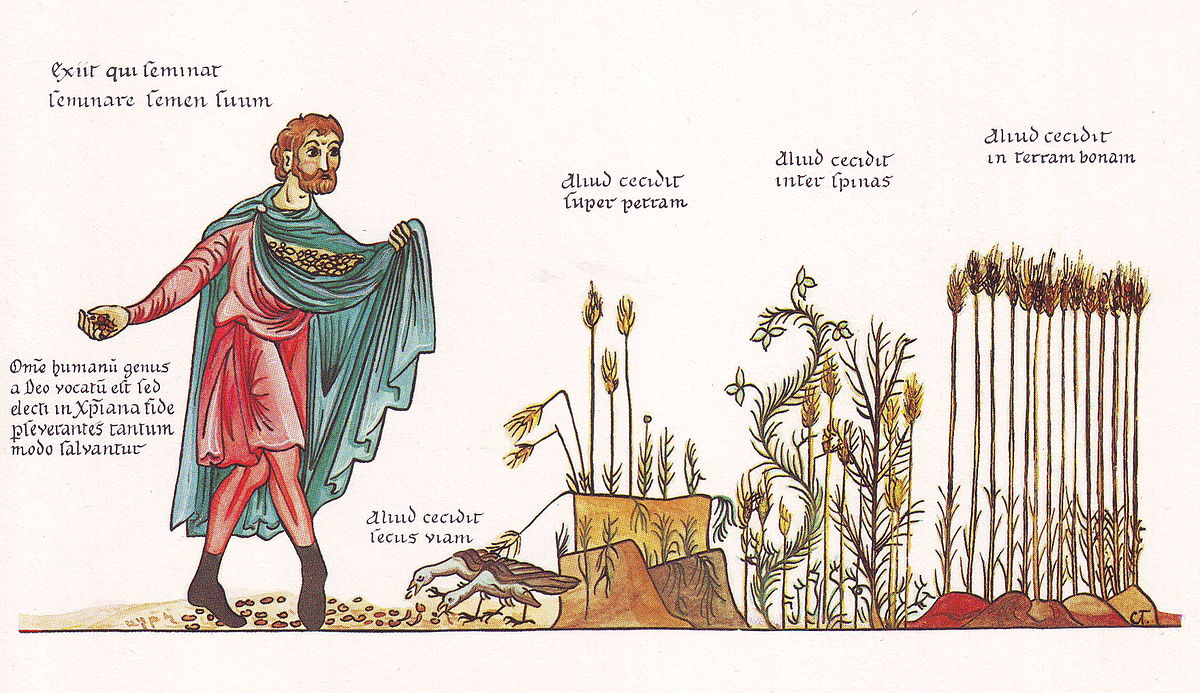

with them and replace them with the Gentile Christian church. A careful reading of the parable in light of its first-century Jewish context can yield important insights.

with them and replace them with the Gentile Christian church. A careful reading of the parable in light of its first-century Jewish context can yield important insights.