by Lois Tverberg

“The sower went out to sow his seed; and as he sowed, some fell beside the road, and it was trampled under foot and the birds of the air ate it up. “Other seed fell on rocky soil, and as soon as it grew up, it withered away, because it had no moisture. “Other seed fell among the thorns; and the thorns grew up with it and choked it out. “Other seed fell into the good soil, and grew up, and produced a crop a hundred times as great.”

As He said these things, He would call out, “He who has ears to hear, let him hear.” His disciples began questioning Him as to what this parable meant. And He said, “To you it has been granted to know the mysteries of the kingdom of God, but to the rest it is in parables, so that seeing they may not see, and hearing they may not understand. “Therefore I speak to them in parables; because while seeing they do not see, and while hearing they do not hear, nor do they understand. ” – Luke 8:4-10

Sometimes parables make us scratch our heads, and it can seem that Jesus was using them to deliberately confuse people. But even though they seem strange to us, they were a traditional teaching method that was always used to clarify rather than obscure.

Looking at this passage in more depth, Jesus is actually explaining why his parables make sense to some people and not to others. Here he tells the parable of the sower – that the same seed that grows well in good soil does not take root on the path, and produces little in rocky or thorny ground. The seed is always good, but the soil of human hearts may or may not be. The reason people don’t understand Jesus’ teachings is not because he is hiding anything. The lack of understanding is a problem with the hearer, not the speaker.

Looking at this passage in more depth, Jesus is actually explaining why his parables make sense to some people and not to others. Here he tells the parable of the sower – that the same seed that grows well in good soil does not take root on the path, and produces little in rocky or thorny ground. The seed is always good, but the soil of human hearts may or may not be. The reason people don’t understand Jesus’ teachings is not because he is hiding anything. The lack of understanding is a problem with the hearer, not the speaker.

The difficulty is beyond just the ability to understand, but to receive his teaching in order to obey it. In Hebrew, the word for hear, “shema,” also means to “obey.” In fact, almost every time the word “obey” is found in English, it has been translated from “shema.” That is how one can hear, but not “hear.”

Another way he says this is by his quotation from the Old Testament. He is quoting Isaiah 6:9-10, when God commissions Isaiah as a prophet to Israel. God did not send Isaiah to confuse the people with obscure teachings, but to clearly proclaim God’s word to them. But God says to Isaiah at his commission almost sarcastically,

Render the hearts of this people insensitive, their ears dull, and their eyes dim, otherwise they might see with their eyes, hear with their ears, understand with their hearts, and return and be healed. – Isaiah 6:10

Really, God is not telling Isaiah to confuse the people, but to proclaim the truth, even though God knows his teaching will be rejected by many. Jesus is saying the same thing – that like the prophets he speaks to clarify God’s word, but from hardness of heart, many will not hear or obey him.

Photo: Sts. Konstantine and Helen Orthodox Church, Cluj, Romania.

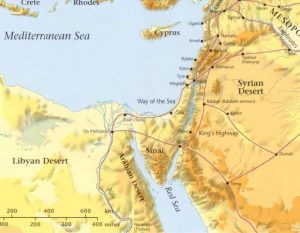

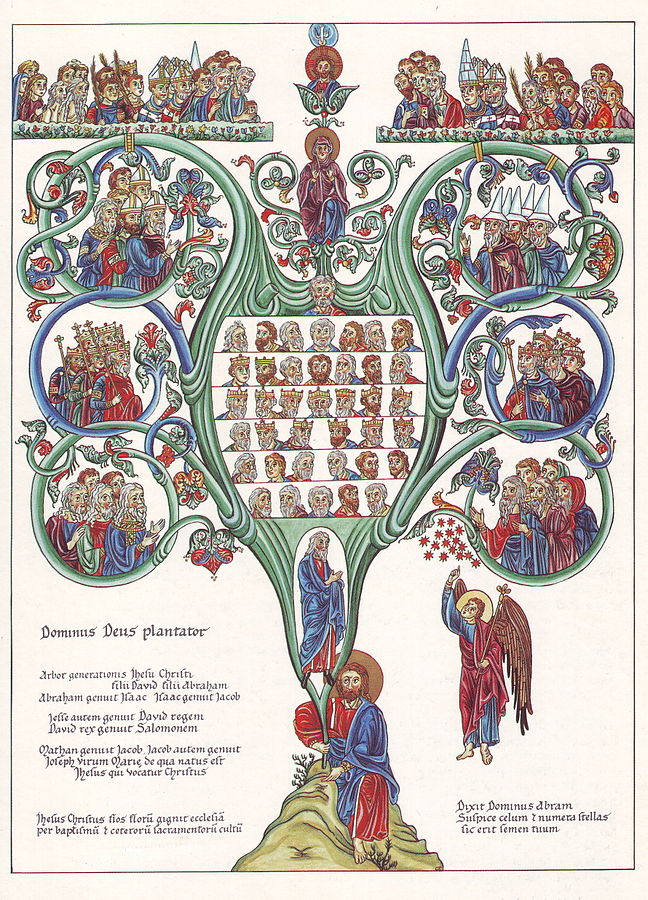

An interesting pattern emerges as we read the stories of Isaac and Jacob carefully. Both of these men had encounters with God, and interestingly, the encounters usually happened when they were traveling into or out of the Promised Land.

An interesting pattern emerges as we read the stories of Isaac and Jacob carefully. Both of these men had encounters with God, and interestingly, the encounters usually happened when they were traveling into or out of the Promised Land.

Then the LORD God called to the man, and said to him, “Where are you?” He said, “I heard the sound of You in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid myself.” And he said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?” The man said, “The woman whom You gave to be with me, she gave me from the tree, and I ate. Then the LORD God said to the woman, “What is this you have done?” And the woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.” Genesis 3:9-13

Then the LORD God called to the man, and said to him, “Where are you?” He said, “I heard the sound of You in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid myself.” And he said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?” The man said, “The woman whom You gave to be with me, she gave me from the tree, and I ate. Then the LORD God said to the woman, “What is this you have done?” And the woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.” Genesis 3:9-13