by Lois Tverberg

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age. (Matt 28:19)

Jesus’ final words were those of what we call the Great Commission — to make disciples of the whole world. But what is a disciple? The ancient, Hebraic picture Jesus had of raising disciples was unique to his Jewish culture. By learning about this practice, we gain fresh insight into how Jesus intended that we fulfill his command.

Jesus’ final words were those of what we call the Great Commission — to make disciples of the whole world. But what is a disciple? The ancient, Hebraic picture Jesus had of raising disciples was unique to his Jewish culture. By learning about this practice, we gain fresh insight into how Jesus intended that we fulfill his command.

Jesus lived in a deeply religious culture that valued biblical understanding more than anything else. To become a great rabbi was the highest goal possible, and just to be a disciple of a famous rabbi was an honor. All boys studied and memorized the scriptures until age twelve, and then learned a trade after that. Only a small minority could keep studying, and only a very few were able to go on to learn with a rabbi.

Rabbis acted as wandering expositors who taught in synagogues and homes, and outdoors when a crowd gathered. They taught general audiences, and also had a small band of disciples who lived with them and followed them everywhere. They traveled from town to town teaching, because no mass-communication was available.

They often practiced a trade of their own, but when traveling they were dependent on the hospitality of the community. Indeed, it was forbidden to charge money to teach, but people were expected to support them and invite them into their homes.

Even to the present day, Judaism retains a tradition of discipleship. When Jewish rabbis are ordained, they are commissioned to “Raise up many disciples.” This is the first verse of Pirke Avot (Wisdom of the Fathers), from the Mishnah, the Jewish compendium of laws and sayings from around Jesus’ time. Texts like this have much to say about the rabbinic method for raising disciples. Another passage that describes discipleship is this:

Even to the present day, Judaism retains a tradition of discipleship. When Jewish rabbis are ordained, they are commissioned to “Raise up many disciples.” This is the first verse of Pirke Avot (Wisdom of the Fathers), from the Mishnah, the Jewish compendium of laws and sayings from around Jesus’ time. Texts like this have much to say about the rabbinic method for raising disciples. Another passage that describes discipleship is this:

Let your house be a meeting place for the rabbis, and cover yourself in the dust of their feet, and drink in their words thirstily. (Avot 1:4)

This text casts light on several stories from Jesus’ ministry in the gospels. Mary, Martha and Lazarus opened their home to Jesus in the tradition of showing hospitality toward rabbis and disciples. Their house would also have served as a place for meetings for him to teach small groups.

We also read that Mary “sat at Jesus’ feet” to learn from him (Luke 10:39), which may be the sense of the phrase “cover yourself in the dust of their feet.” The phrase may also have meant to walk behind him to listen to him teach, as Jesus’ disciples would have done. On the unpaved roads in Israel, they literally would have been covered in their rabbi’s dust. (1)

What was expected of rabbis and disciples?

Rabbis were expected not only to be greatly knowledgeable about the Bible, but to live exemplary lives to show that they had taken the scriptures to heart. The objective of their teaching was to instill in their disciples both the knowledge and desire to live by God’s word. It was said, “If the teacher is like an angel of the Lord, they will seek Torah from him. If not, they will not seek Torah from him” (Babylonian Talmud, Hagigah 15b).

The disciple’s goal was to gain the rabbi’s understanding, and even more importantly, to become like him in character. It was expected that when the student became mature enough, he would take his rabbi’s teaching out to the community, add his own understanding to it, and raise up disciples of his own.

A disciple was expected to leave family and job behind to join the rabbi in his austere lifestyle. They would live twenty-four hours a day together, walking from town to town, teaching, working, eating, and studying. As they lived together, they would discuss the scriptures and apply them to their lives.

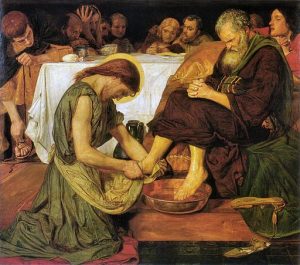

The disciples were supposed to be the rabbi’s servants, submitting to his authority while they assisted him in his tasks. Indeed, the word “rabbi” means “my master,” and was a term of great respect, the same title that a slave would use to address his owner.

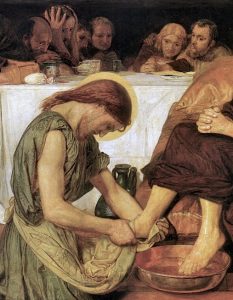

This sheds new light on the story of when Jesus washed the disciples’ feet. Jesus was entitled to having them wash his feet, not the other way around! By his actions he was teaching them a critical lesson in humility — that the one most deserving of being served is himself serving, while they were arguing who is the greatest. Jesus was using typical rabbinic technique: he didn’t just lecture, he used his own behavior as an example.

This sheds new light on the story of when Jesus washed the disciples’ feet. Jesus was entitled to having them wash his feet, not the other way around! By his actions he was teaching them a critical lesson in humility — that the one most deserving of being served is himself serving, while they were arguing who is the greatest. Jesus was using typical rabbinic technique: he didn’t just lecture, he used his own behavior as an example.

The rabbi-disciple relationship was very intimate. The rabbi was considered to be closer than a father to his disciples, and disciples were sometimes called “sons.” When Peter said “Even if I have to die with you, I will not deny you,” he was reflecting the deep love and commitment that disciples had for their rabbi (Matt. 26:35).

In contrast, Judas’ betrayal would have been unthinkable, even if Jesus had not been the Messiah. Jesus’ insistence that his disciples leave everything behind to follow him would not have been considered extreme in that culture. They held up the image of Elisha as a model of a disciple’s commitment, who burned his plow and left everything to become Elijah’s disciple (1 Kings 19). After Elisha had lived with Elijah and served him for many years, he received Elijah’s authority to go out as his successor, as the disciples did from Jesus.

What light does this shed on the Great Commission?

Jesus’ eastern method of discipleship gives us a new picture of what he called us to do. Our Western model focuses mainly on the gospel as information, and our goal is to be a person of correct understanding. We focus mainly on spreading information about Jesus, not on living our life like him and inspiring others to do the same.

While it is important to teach and defend truth, Jesus’ method of discipleship is much more than that. He began his Kingdom by walking and living with disciples, to show them how to be like him. Then they went out and made disciples, doing their best to imitate Jesus and show others by their own example.

Jesus expects his kingdom will be built in this way: as each person grows in maturity, they live their lives transparently before others, counseling them on what they have learned about following Christ. The kingdom is built primarily through these close relationships of learning, living and teaching.

Paul uses the same model of discipleship in his ministry. He said,

…in Christ Jesus I became your father through the gospel. Therefore I urge you to imitate me. For this reason I am sending to you Timothy, my son whom I love, who is faithful in the Lord. He will remind you of my way of life in Christ Jesus, which agrees with what I teach everywhere in every church. (1 Cor 4:15-17)

We can hear that Paul’s goal for the Corinthians is that they become disciples, who change their lives to be like Christ, not just learn the correct beliefs. Using rabbinic method, he likens himself as a father to them, and he send his disciple Timothy, who he calls “his son.” He wants them to learn by the example of Timothy about his own way of life, which is a reflection of Jesus’ teaching. Paul is using this “whole person” method of evangelism to transform their lives, not just their minds, to reflect the truth.

Through this model of discipleship, we see that Jesus isn’t just interested in having our minds. He wants our hearts and lives too. Once our lives reflect what our minds believe, then the belief has actually reached our hearts. Then our passion for following him becomes a loud witness that inspires others to do the same.

~~~~

To further explore the rabbi/disciple relationship and its implications for Christians today, see chapter 4, “Following the Rabbi” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 51-65.

To further explore the rabbi/disciple relationship and its implications for Christians today, see chapter 4, “Following the Rabbi” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 51-65.

For further reading on discipleship in the first century, see New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus, En-Gedi Resource Center, 2006.

For further reading on discipleship in the first century, see New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus, En-Gedi Resource Center, 2006.

(1) Mishnah, Avot 1:4, attributed to Yose ben Yoezer, about 180 BCE. An in-depth discussion of being “covered in the dust of one’s rabbi” can be found at this link.

Photos: Christ Great Commission icon [CC BY-SA 2.0], Duccio di Buoninsegna [Public domain], Ford Madox Brown [Public domain], Wikipedia

The Lord’s Prayer is loaded with meaning that we don’t fully appreciate because of cultural differences.1 In particular, the phrase “hallowed be your name” sounds foreign to us. This phrase is very rich in its original context and has an important lesson for our calling as Christians.

The Lord’s Prayer is loaded with meaning that we don’t fully appreciate because of cultural differences.1 In particular, the phrase “hallowed be your name” sounds foreign to us. This phrase is very rich in its original context and has an important lesson for our calling as Christians.