by Lois Tverberg

“Whoever of you loves life and desires to see many good days, guard your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking deceitfully.” Psalm 34:12-13, quoted in 1 Peter 3:10

The writer of Psalm 34 reminds us that the key to a long life of good days is to “guard your tongue from evil.” There has been much thought on the question of what is an “evil tongue” by Jews since the time of Jesus.

In Hebrew, words “the evil tongue” are translated as Lashon Hara (La-SHON Hah-RAH). This term is used for gossip – in particular, defaming someone to others by revealing negative details about them. Lashon Hara is different from slander, which is telling lies about others.

Lashon Hara is telling co-workers about how the boss bungled his presentation, or telling your husband how poorly the worship leader sings. This habit tears down friendships, demeans others, and undermines trust. There are, of course, a few times damaging information needs to be relayed, but otherwise, this speech is usually very destructive.

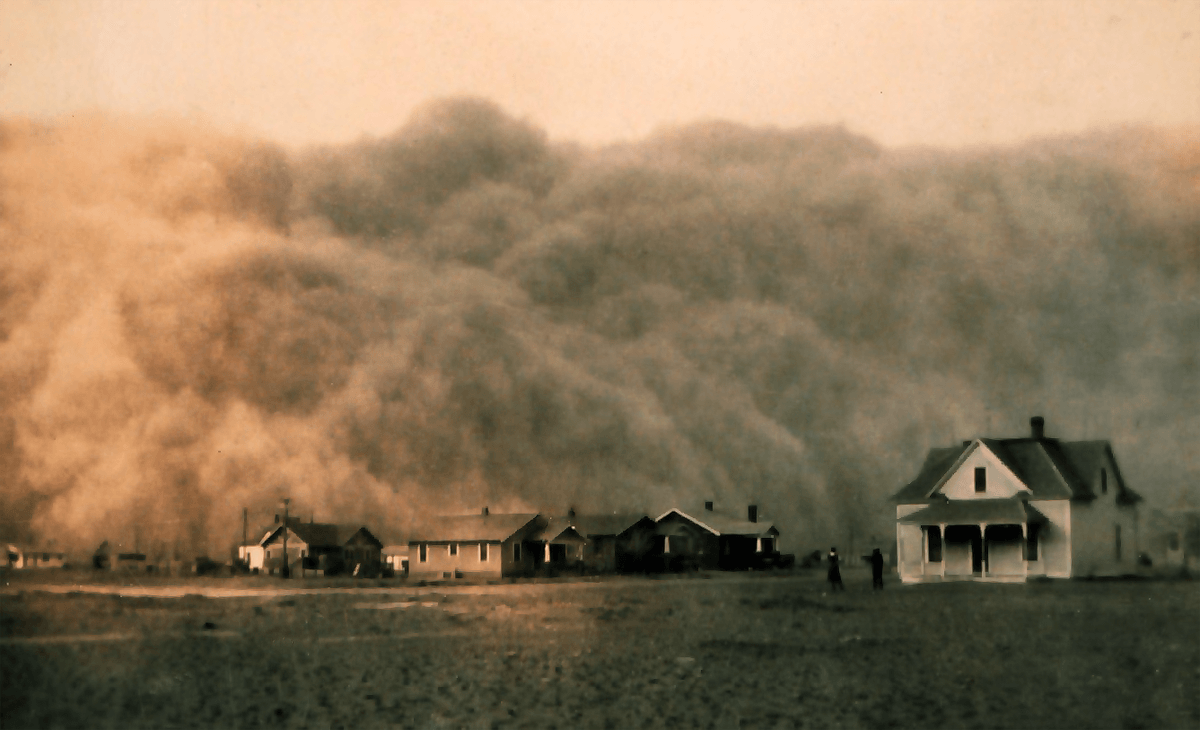

The rabbis point out that other actions close to Lashon Hara should be avoided as well. For instance, to read a newspaper editorial that you don’t like and then show it to someone just so they will scoff is called the “Dust of Lashon Hara.” It also includes sarcastic comments about another person, like, “She is such a genius, isn’t she?” Even to sneer when someone else gossips qualifies, because it communicates your negative feelings. It truly is a difficult task to avoid damaging others through subtle comments and even body language.

How do we heal our speech so that our relationships can be more fulfilling? Jesus says, “Out of the overflow of the heart the mouth speaks.” (Matthew 12:34) He diagnoses the problem as one of the heart. One major culprit behind gossip is our desire to see others’ actions in the worst light possible. If a friend doesn’t invite you to a party, was it an oversight, or was there malicious intent? A person who assumes the worst will want to report the slight to everyone, but a person who assumes the best will not be bothered. Our whole attitude toward others changes when we try always to give others the benefit of the doubt.

Another major reason for unkind speech is our desire to elevate ourselves by tearing others down. It may work temporarily, but over time demeans us in the eyes of others. Paul has a solution: “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit, but in humility consider others better than yourselves. Each of you should look not only to your own interests, but also to the interests of others.” (Philippians 2:3-4) If we genuinely care as much about others as ourselves, we will try to protect their reputation as much as we do our own.

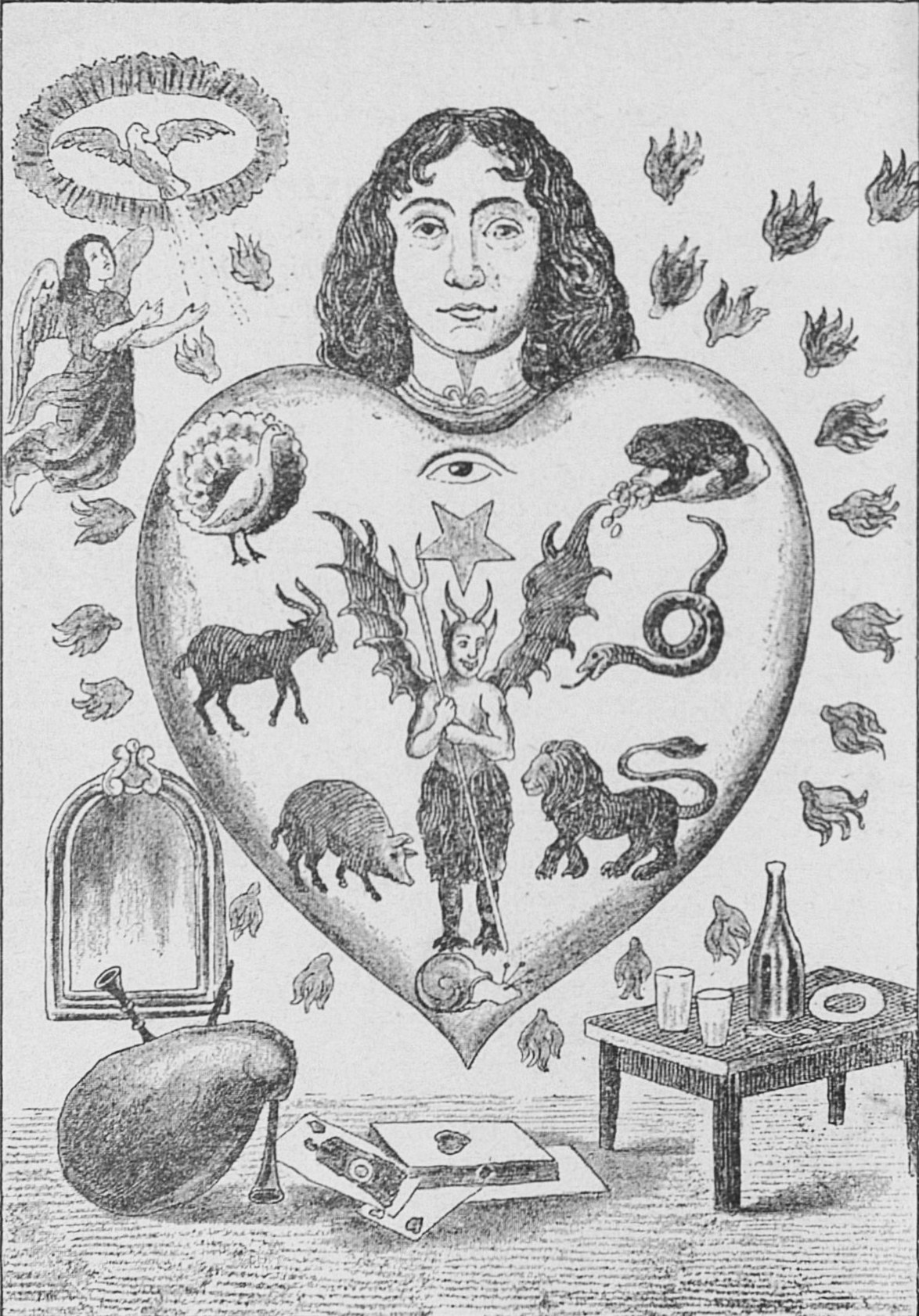

people to obey God’s word and stay far from sin. One technique they employed was to point out how seemingly small sins can evolve into much greater sins. (1) This was called kalah ka-hamurah (“light as heavy”), an abbreviation of mitsvah kalah ka-mitsvah hamurah (“a light commandment is like a heavy commandment”). In other words, kalah ka-hamurah relays the sense that breaking a less significant law is linked to breaking a greater law. The same style of logic appears in Jesus’ teaching when he compares anger to murder and lust to adultery (Mt 5:22-23, 27-28).

people to obey God’s word and stay far from sin. One technique they employed was to point out how seemingly small sins can evolve into much greater sins. (1) This was called kalah ka-hamurah (“light as heavy”), an abbreviation of mitsvah kalah ka-mitsvah hamurah (“a light commandment is like a heavy commandment”). In other words, kalah ka-hamurah relays the sense that breaking a less significant law is linked to breaking a greater law. The same style of logic appears in Jesus’ teaching when he compares anger to murder and lust to adultery (Mt 5:22-23, 27-28).