by Lois Tverberg

If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s descendants,

heirs according to promise. (Galatians 3:29)

Many of us scratch our heads at why there are so many long lists of genealogies in the Bible. Our modern, individualistic Western culture makes it difficult for us to see an important theme that would have been obvious to its ancient audience — the centrality of family.

Not only is family critical in the Old Testament, it is key to some very important controversies in the New Testament as well, such as including Gentiles among the growing movement of Jewish believers in Jesus. Grasping the ideas that ancient peoples had about the family, and how these themes play out can help us understand our Bibles from beginning to end.

The Ancient Idea of Family

First, we need know that the ancient Hebrews valued family and heritage beyond anything else — it was absolutely everything in terms of a person’s identity and life goals. A person didn’t derive his identity from his occupation, but from his or her family. It was expected that children would take on their father’s profession and spiritual life.

It was also understood that children would take on their father’s personality — if a father was wise, his descendants would be wise; if he was warlike, his descendants would be warlike. Explaining what each family was like and relationships between families was very important to understanding the society as a whole.

Stories about the founders of each family were important because they were key to each family’s self-definition. This helps us to see why some biblical stories are included that don’t seem to be moral examples for us. For instance, we are told that Lot’s daughters got him drunk and had relations with him, and Moab was born, who was the father of the Moabites (Gen. 19:37).

Why are we told this? Because later in history, the Moabite women seduced the Israelites into sexual immorality (Num. 25:1). There are even hints of this in the story of Ruth, the Moabites, and her encounter with Boaz, but she was a “woman of noble character” (as Boaz said in Ruth 3:11), unlike her ancestors. We can see from this how the Moabite family’s “personality” affected its actions over many generations, and how a key to reading the Old Testament is to be aware of the associations with each family.1

Besides knowing the stories of the family’s fathers, another important thing in biblical cultures would be to understand how the inheritance was given. Typically the first-born son would receive a double portion of the inheritance and become the spiritual leader of the family, and the rest of the children would honor him, even from youth. He was considered to be the “first-fruits of his father’s vigor,” evidence of his father’s ability to leave a legacy, a source of manly pride.

Interestingly, the Bible makes an effort to point out that God did not allow his blessing to be given to any significant firstborn in the line of Abraham, including the sons of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Judah, Jesse and David!2 He was showing that the nation was established through his power, not through human achievement. The only prominent firstborn in the Bible is Jesus, who did not have an earthly father at all, but of whom God said, “This is my beloved son, in whom I delight” (Matt 3:17)!

The Epic of Abraham’s Family

Knowing this shows us the rationale for God’s covenant with Abraham. Abraham was a man of great faith, who, at God’s request, gave up his own ancestral family and homeland, a great sacrifice in that time. When God first appeared to him he was childless, which was understood to be a terrible curse, the ultimate failure in life.

Because of his unwavering faith God promised him the greatest of blessings — that he would be the father of many nations. In biblical culture, becoming the father of a great nation would have been an enduring legacy of honor, like being elected president today.

Because of his unwavering faith God promised him the greatest of blessings — that he would be the father of many nations. In biblical culture, becoming the father of a great nation would have been an enduring legacy of honor, like being elected president today.

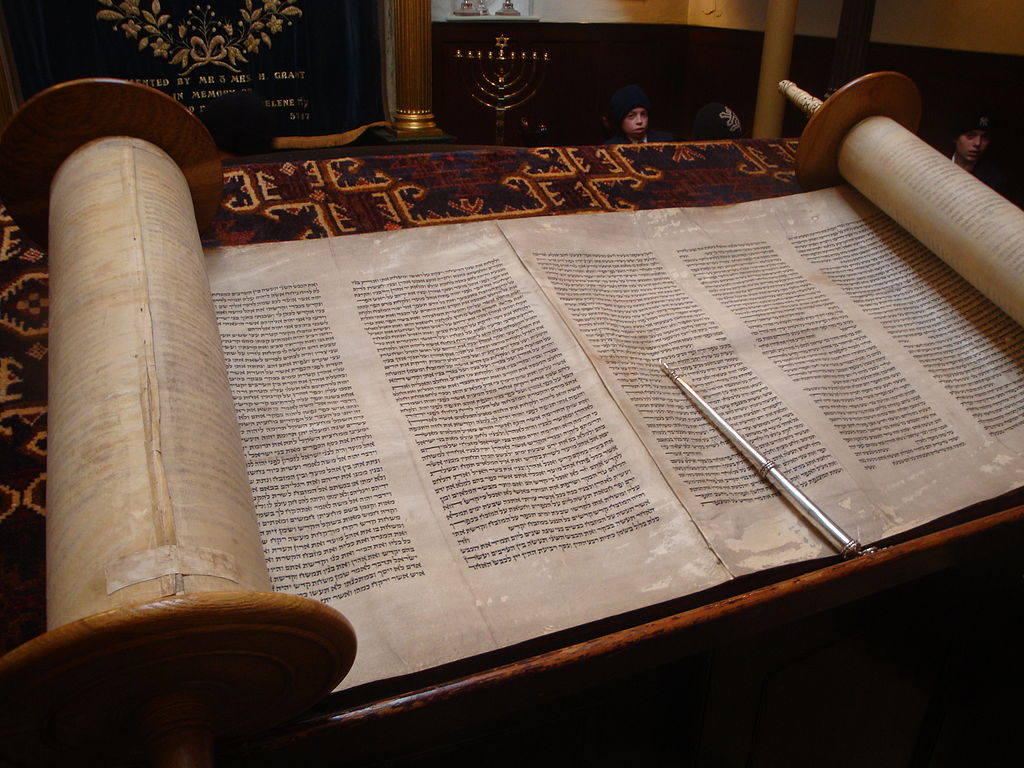

Because it was assumed that the members of a family would be like their forefathers, it made sense that Abraham would instill in his children his strong faith in God, and a great nation of believers would result. God’s covenant with Abraham was specifically with him and his future descendants, and the “sign” of the covenant, the physical remembrance, was circumcision, which was required of all males from Abraham’s time until this day.

The sign of the covenant is not coincidental — rather, it marked the fact that the covenant was with Abraham’s “seed,” passed down through each generation of the family. Each time descendants are listed it showed that God had been honoring his covenant.

In the time of Jesus and Paul, there seemed to be quite a debate over who was a “son of Abraham,” with the understanding that a person’s salvation was linked to being a part of the covenantal family. John the Baptist warned people not to trust in their lineage when he said, “Do not suppose that you can say to yourselves, `We have Abraham for our father’; for I say to you that from these stones God is able to raise up children to Abraham” (Matt. 3:9).3

Jesus had a heated discussion with some leaders on this very topic:

[Jesus said,] “I know you are Abraham’s descendants. Yet you are ready to kill me, because you have no room for my word. I am telling you what I have seen in the Father’s presence, and you do what you have heard from your father.” “Abraham is our father,” they answered. “If you were Abraham’s children,” said Jesus, “then you would do the things Abraham did. As it is, you are determined to kill me, a man who has told you the truth that I heard from God. Abraham did not do such things. You are doing the things your own father does.” (John 8:37- 41)

Behind this conversation seems to be the idea that they were claiming to be part of the “saved” because Abraham was their father. Jesus questions this, and points out that he expects that if they were sons of Abraham, they would then be like him.

Paul’s Understanding of the Sons of Abraham

In Paul’s writing too, he deals with the idea that being a “son of Abraham,” a circumcised Jew, was necessary for salvation. Christians have traditionally read Paul’s arguments over circumcision as a contrast between grace and legalism. Recent scholarship suggests that a greater issue was whether God could extend his salvation to others outside the family of Abraham.4

In Paul’s writing too, he deals with the idea that being a “son of Abraham,” a circumcised Jew, was necessary for salvation. Christians have traditionally read Paul’s arguments over circumcision as a contrast between grace and legalism. Recent scholarship suggests that a greater issue was whether God could extend his salvation to others outside the family of Abraham.4

A strong sense of nationalism and isolationism was among Jews of the first century, who were a small minority in the Roman Empire, and who had gone through much persecution for not adopting Hellenistic ways. About 150 years before Christ, Jews were executed if they circumcised their sons in order to be faithful to God.

As a reaction to that persecution and to the encroaching Gentile world, they put great emphasis on observing laws that separated them from Gentiles, as a way to show their commitment to God. Being circumcised was especially important because it marked them as “sons of Abraham,” and part of the family covenant. To them, it undermined God’s covenant with Abraham to extend it to others who had not become full proselytes to Judaism.

Interestingly, Paul does not say that a person doesn’t need to be a son of Abraham to be saved. Rather, he deals with this issue by redefining what a “son of Abraham” is, by stretching the definition to include the Gentiles, the very group not included in the definition of a “son of Abraham”! He points out that Abraham himself was a Gentile, and that God’s promise was given to him because of his faith, before he was circumcised. He says,

Is this blessedness only for the circumcised, or also for the uncircumcised? We have been saying that Abraham’s faith was credited to him as righteousness. Under what circumstances was it credited? Was it after he was circumcised, or before? It was not after, but before! And he received the sign of circumcision, a seal of the righteousness that he had by faith while he was still uncircumcised. So then, he is the father of all who believe but have not been circumcised, in order that righteousness might be credited to them. (Romans 4:9-11)

In Galatians, Paul makes a similar point:

Even so Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness. Therefore, be sure that it is those who are of faith who are sons of Abraham. The Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, “All the nations (Gentiles, goyim) will be blessed through you.” (Galatians 3:7)

Paul is interpreting the words of God’s promise to Abraham to say that He would bless the goyim, (meaning both “nations” and “Gentiles”) through him. He is pointing out that God’s blessings are not just for his biological descendants who were circumcised, but also for the Gentiles of the world, but yet they still come through Abraham. From this, Paul can conclude that Gentile believers in God are true sons of Abraham. In his words from Galatians 3:28-29 he concludes,

“There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s descendents, and heirs according to the promise.”

~~~~

1 Another story that continues over generations is the battle with the Amelekites, and key to understanding it is the family relationships between the generations. See “Esther, The Rest of the Story.”

2 The issue of who would get the blessing of the firstborn is a theme throughout Genesis, and especially the story of Joseph and his brothers. The special coat from Jacob indicated that he had appointed Joseph firstborn, because he was the first son of Rachel, the wife he loved. Jacob once said to his family, “My wife bore me two sons” (Gen.44:27) virtually disowning Leah’s family entirely. We can see why Joseph dreamed that his family would bow down to him, and why his older brothers wanted to kill him, to eliminate him as heir. For more, see “All in the Family.”

3 It is likely that they felt that being a “son of Abraham” insured that their sins would be forgiven. See “God’s Illogical Logic of Mercy.“

4 For more about Paul’s arguments in their Jewish context, see “The Context of Paul’s Conflict.”

Photos: Ojedamd [CC BY-SA 3.0], Movieevery, Hult, Adolf, 1869-1943;Augustana synod. [from old catalog] [No restrictions]

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).