by Lois Tverberg

Tell the whole community of Israel that on the tenth day of this month each man is to take a lamb for his family, one for each household… Take care of them until the fourteenth day of the month, when all the people of the community of Israel must slaughter them at twilight. Then they are to take some of the blood and put it on the sides and tops of the doorframes of the houses where they eat the lambs… The blood will be a sign for you on the houses where you are; and when I see the blood, I will pass over you. No destructive plague will touch you when I strike Egypt. (Exodus 12:3-4, 6-7, 12)

What was the significance of putting blood on the doorposts? One very important thing to realize is how it foreshadows the future shedding of blood of Christ, that protects us from judgment, just as the blood here protected the families from judgment.

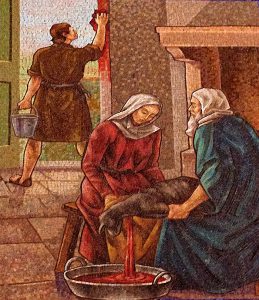

But yet, the act of putting blood on the doorposts says other things as well. One is that it was a public commitment to the God of Israel in that hostile land, in which that kind of sacrifice was an abomination, which would lead to the person’s being stoned (Ex. 8:26). Only those that were convinced that God would triumph over the Egyptian gods would have done so because of fear of public execution.

But yet, the act of putting blood on the doorposts says other things as well. One is that it was a public commitment to the God of Israel in that hostile land, in which that kind of sacrifice was an abomination, which would lead to the person’s being stoned (Ex. 8:26). Only those that were convinced that God would triumph over the Egyptian gods would have done so because of fear of public execution.

Also, putting the blood on the doorposts was a mark of faith that apparently was not limited to Israelites, but anyone who placed his or her faith in God. The text says that many others left Egypt with the Israelites (Ex. 12:38) – perhaps they too had claimed this God by marking their homes. Even some of Pharaoh’s officials feared the Lord – could some of them have even done it? Interestingly, entire homes and families were saved, just as in the New Testament, entire families were baptized and saved (Acts 16:34). Even Rahab the harlot was able to save her family by marking her home with a scarlet cord! (Josh. 6:25) The Bible often talks about salvation in terms of families, while we think in terms of individuals.

Finally, it is amazing that God told people to make a sacrifice and put the blood on their homes. Normally sacrifices were made at an altar in a tabernacle or temple, and only the ceremonially clean could enter in. God’s great shekinah glory would be very present at the altar, apart from the rest of the people. Here, God was telling them to anoint their home as God’s altar, and publically place their faith in him. God’s presence came that night and to those who did not fear him, it lead to judgment. But to those who had faith, it would set them free.

the bitterness of slavery, and parsley dipped in salt water to remember the tears that their ancestors shed. Along with dry, unleavened bread, these items are the only foods available through the long ceremony that precedes the Passover dinner, which begins very late. As they talk about God’s redemption of people from Egypt, the people relive that hardship for just an hour while they are hungry for dinner but have only dry bread and bitter herbs to eat. Finally, they feast on a meal of wine and meat and wonderful food, reminding themselves of the joy of God’s redemption.

the bitterness of slavery, and parsley dipped in salt water to remember the tears that their ancestors shed. Along with dry, unleavened bread, these items are the only foods available through the long ceremony that precedes the Passover dinner, which begins very late. As they talk about God’s redemption of people from Egypt, the people relive that hardship for just an hour while they are hungry for dinner but have only dry bread and bitter herbs to eat. Finally, they feast on a meal of wine and meat and wonderful food, reminding themselves of the joy of God’s redemption. e LORD said to Moses, “When you go back to Egypt see that you perform before Pharaoh all the wonders which I have put in your power; but I will harden his heart so that he will not let the people go. – Exodus 4:21

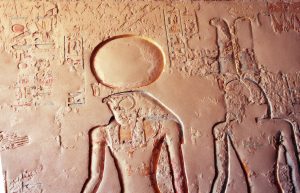

e LORD said to Moses, “When you go back to Egypt see that you perform before Pharaoh all the wonders which I have put in your power; but I will harden his heart so that he will not let the people go. – Exodus 4:21 Israelites, but to declare that God was supreme over the many “gods” that Egypt worshipped (Ex.

Israelites, but to declare that God was supreme over the many “gods” that Egypt worshipped (Ex. Many of us struggle with the fact that God said that he would harden Pharaoh’s heart, so that God could bring all ten plagues on Egypt before he finally would free the Israelites. It seems like Pharaoh might be innocent pawn which God callously manipulates.

Many of us struggle with the fact that God said that he would harden Pharaoh’s heart, so that God could bring all ten plagues on Egypt before he finally would free the Israelites. It seems like Pharaoh might be innocent pawn which God callously manipulates. They meant that this was the sign of a power far, far greater than they could conjure up. Often God’s power or intervention is described metaphorically by using words like God’s “arm” or God’s “hand.” God’s “finger” also refers to his power or intervention. God is so mighty that all he had to use was his littlest finger to defeat the powers of the magicians in Egypt!

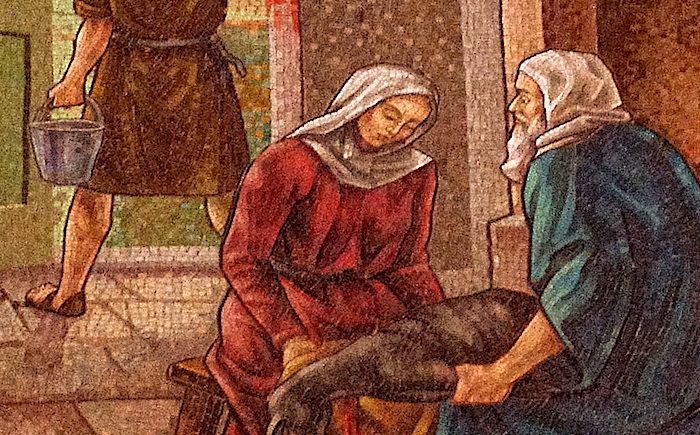

They meant that this was the sign of a power far, far greater than they could conjure up. Often God’s power or intervention is described metaphorically by using words like God’s “arm” or God’s “hand.” God’s “finger” also refers to his power or intervention. God is so mighty that all he had to use was his littlest finger to defeat the powers of the magicians in Egypt! In the first few chapters of Exodus, women play a major role. Pharaoh tells the midwives Shiprah and Puah to kill the newborn boys but let the girls live. His assumption was that while men posed a threat, women would be easily assimilated into Egyptian culture and exploited as domestic and sexual slaves. We also see hints of this in Abraham’s time, when he tells Sarah that the Egyptians would kill him and take her. (Genesis 12:12)

In the first few chapters of Exodus, women play a major role. Pharaoh tells the midwives Shiprah and Puah to kill the newborn boys but let the girls live. His assumption was that while men posed a threat, women would be easily assimilated into Egyptian culture and exploited as domestic and sexual slaves. We also see hints of this in Abraham’s time, when he tells Sarah that the Egyptians would kill him and take her. (Genesis 12:12)

The rabbis pointed out that this pattern of the punishment fitting the crime is a recurring theme throughout the Scriptures. Because Jacob deceived Isaac in his blindness into giving him the birthright, Jacob is fooled into marrying Leah when he is “blind” – when she is brought to him veiled, and in the night he doesn’t see his new wife. Or, because Pharaoh killed the Israelite boys by drowning them in the river, God defeated his army by drowning them too. Haman was hanged on the gallows that he prepared for Mordechai. The rabbis called this pattern “measure for measure” – midah keneged midah.

The rabbis pointed out that this pattern of the punishment fitting the crime is a recurring theme throughout the Scriptures. Because Jacob deceived Isaac in his blindness into giving him the birthright, Jacob is fooled into marrying Leah when he is “blind” – when she is brought to him veiled, and in the night he doesn’t see his new wife. Or, because Pharaoh killed the Israelite boys by drowning them in the river, God defeated his army by drowning them too. Haman was hanged on the gallows that he prepared for Mordechai. The rabbis called this pattern “measure for measure” – midah keneged midah.