by Lois Tverberg

The light of the body is the eye: if therefore thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light. But if thine eye be evil, thy whole body shall be full of darkness. Matthew 6:22-23 KJV

What does Jesus mean in the strange passage above when he refers to having “a single eye”? Figures of speech in other documents from that time help illuminate Jesus’ puzzling words. Several idioms that mentioned the “eye” were about a person’s attitude toward others. A person who possessed a “good eye” was generous toward others, and a person with a “bad eye” was stingy and self-centered.

It has been suggested that Jesus was referring to having a “good eye,” but the Greek in the passage actually does not say “good” (kalos), rather it says “single” (haplous).

In fact, being “single” is not an uncommon idiom in that time, however, not in the precise sense we understand it today. Throughout the New Testament the idea of “singleness” (haplotes) is used to mean “sincere” or “undivided,” often in exhortations to have a “single heart” (See 2 Cor. 1:12, 11:3, Eph. 6:5, Col. 3:22). Sincerity and lack of duplicity seems to be the idea of the following passage:

The good man has not an eye of darkness that cannot see; for he shows mercy to all men, sinners though they may be, and though they may plot his ruin.…His good mind will not let him speak with two tongues, one of blessing and one of cursing, one of insult and one of compliment, one of sorrow and one of joy, one of hypocrisy and one of truth, one of poverty and one of wealth; but it has a single disposition only, simple and pure, that says the same thing to everyone. (1)

This passage describes a man’s “eye” in terms of his caring for the needs of others, and contrasts an “eye of darkness” to a disposition of “singleness”. The contrast seems to be between pretending to care about others with an inward attitude of self-advancement and of having a genuine concern for others, without hidden motives.

And, we do actually find the idiom of having a “single eye” in Jesus’ time too:

I never slandered anyone, nor did I censure the life of any man, walking as I did in singleness of eye (3:4)… And now hearken to me, my children, and walk in singleness of heart….The single [minded] man covets not gold.…There is no envy in his thoughts, nor [does he] worry with insatiable desire in his mind. For he walks in singleness, and beholds all things in uprightness of heart….Keep, therefore, my children, the law of God, and attain singleness…(2)

Here, the idea of “singleness” was associated with a freedom from envy of money. “Singleness” in this passage refers to a person of sincerity who does not have a secret agenda of self-advancement. This translates into a lack of covetousness and greed.

Now Jesus’ words in Matthew 6:22-23 gain more clarity in their context. Jesus seems to be talking about our attitude towards others. Do we have a simple desire to serve God by caring for the needs of others? Or are we insincere people who are self-centered and serving our own agenda? If all we recognize is our own needs, we are blind indeed.

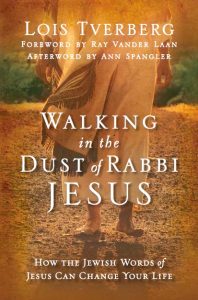

To explore this topic more, see chapter 5, “Gaining a Good Eye” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 69-80.

To explore this topic more, see chapter 5, “Gaining a Good Eye” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 69-80.

(1) Testament of Benjamin 4:2-3 The Testament of Benjamin is of the body of literature called the “pseudepigrapha” — Jewish writings from 200 B.C. to 200 A.D. that are not canonical, but are helpful for showing the cultural expressions and religious understandings of that time.

(2) Testament of Issachar, 3:4, 4:1-2, 5-6; 5:1 Also from the pseudepigrapha.

For more this, see the article, “If Your Eye Be Single” by Steven Notley at www.jerusalemperspective.com.

Photo: Vladimer Shioshvili and Marc Baronnet

From that time Jesus began to show His disciples that He must go to Jerusalem, and suffer many things from the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and be raised up on the third day. Matthew 16:21

From that time Jesus began to show His disciples that He must go to Jerusalem, and suffer many things from the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and be raised up on the third day. Matthew 16:21 Frequently Jesus speaks about how God deals with people by using animals as an example. God watches over the sparrow (10:29) and provides for the ravens (Luke 12:24). So wouldn’t he watch over us too?

Frequently Jesus speaks about how God deals with people by using animals as an example. God watches over the sparrow (10:29) and provides for the ravens (Luke 12:24). So wouldn’t he watch over us too?

Then, later, in Genesis 2, it says that God formed the man from the dust of the ground and then describes how woman was taken out of the first man. At first, these two creation accounts seem to be in disagreement – were both male and female created at the same time, as in 1:27, or was the man formed first and the woman later, as in chapter 2?

Then, later, in Genesis 2, it says that God formed the man from the dust of the ground and then describes how woman was taken out of the first man. At first, these two creation accounts seem to be in disagreement – were both male and female created at the same time, as in 1:27, or was the man formed first and the woman later, as in chapter 2?