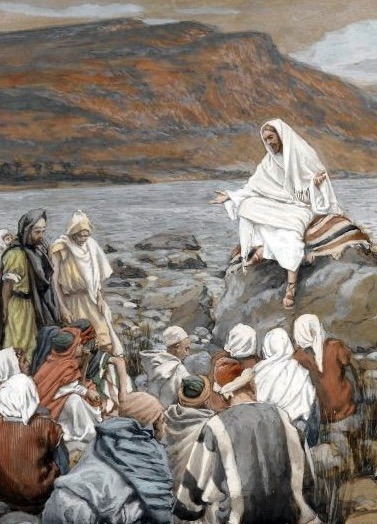

We have lost sight of Jesus’ Jewish teaching methods over the centuries, as the church has moved from its Jewish beginnings to being almost entirely Gentile. This was partly from a desire to stress Jesus’ deity instead of his human context, and partly from an unfortunate desire to divorce Jesus from his Jewish background.

We have lost sight of Jesus’ Jewish teaching methods over the centuries, as the church has moved from its Jewish beginnings to being almost entirely Gentile. This was partly from a desire to stress Jesus’ deity instead of his human context, and partly from an unfortunate desire to divorce Jesus from his Jewish background.

Several years ago, a group of Christian and Jewish scholars started studying Jesus from a different angle. They saw that the more they situated Jesus’ teachings into their Judaic context, the more they could make sense of texts that have made translators scratch their heads for centuries.

They were in agreement that while Jesus was a Jewish rabbi like many others, he did do miracles and claim to be the Messiah. He even made statements that asserted his close association with God and unique authority to speak on God’s behalf. The more that this scholarly group studied Jesus’ use of Jewish teaching methods, the stronger his claims got! [1] They have shown us that Jesus used many rabbinic teaching methods.

The Parable

Over a thousand parables are on record from other Jewish rabbis that bear many similarities in style and content to those of Jesus. In the past, scholars have said that Jesus didn’t invent this form of teaching, but was a master at using it for his purposes. In fact, Jesus’ parables are some of the earliest recorded, and very sophisticated for their day.[2]

The assertion that Jesus simply reused stock parables and revised them for his purposes doesn’t seem convincing now. Rather, it looks more like Jesus was at the very forefront of this classically Jewish teaching genre.

Where can you find parables that have a very similar form than those of Jesus? You will not find them in the literature of the first century like the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo or Josephus. You find them in rabbinic literature from the 2nd and 3rd century and later, surprisingly.

A parable was a way to explain a theological truth in terms of concrete images. Jesus’ Hebrew culture used physical images to express abstractions. For instance, “God’s outstretched arm” meant God’s power, and “to be stiff-necked” is to be stubborn, etc. The parable was an extension of the cultural habit of explaining truth in physical pictures. A parable usually had one main point that it was meant to explain, and some elements were common motifs in many parables.

For instance, a king was often the subject of the parable, and the king was almost always symbolic of God. Parables were the main way Jews communicated their theology of God. One rabbinic parable says,

When a sheep strays from the pasture, who seeks whom? Does the sheep seek the shepherd, or the shepherd seek the sheep? Obviously, the shepherd seeks the sheep. In the same way, the Holy One, blessed be He, looks for the lost.

We can hear the similarity between this parable and Jesus’ parable about the shepherd leaving the ninety-nine to look for the one lost sheep. Both parables may be from a common tradition of thinking of God as a shepherd, from Ezekiel 34, which likens God to a shepherd that looks for his lost sheep. It is interesting that even other rabbis assumed that God pursues the lost himself, and doesn’t stand at a distance while they find their way home.

Kal V’homer

Another method of teaching Jesus used was called Kal v’homer, meaning “light and heavy.” It was of teaching a larger truth by comparing it to a similar, but smaller situation. Often the phrase “how much more” would be part of the saying. Jesus used this when he taught about worry:

Consider how the lilies grow. They do not labor or spin. Yet I tell you, not even Solomon in all his splendor was dressed like one of these. If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today, and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, how much more will He clothe you, O you of little faith! (Luke 12:27-28)

We also see it in parables where he doesn’t necessarily use the phrase “how much more”:

Then Jesus told his disciples a parable to show them that they should always pray and not give up. He said: “In a certain town there was a judge who neither feared God nor cared about men. And there was a widow in that town who kept coming to him with the plea, ‘Grant me justice against my adversary.’ “For some time he refused. But finally he said to himself, ‘Even though I don’t fear God or care about men, yet because this widow keeps bothering me, I will see that she gets justice, so that she won’t eventually wear me out with her coming!’” And the Lord said, “Listen to what the unjust judge says. And will not God bring about justice for his chosen ones, who cry out to him day and night? Will he keep putting them off? I tell you, he will see that they get justice, and quickly. (Luke 18: 1-8)

Here we see an unjust judge finally grants justice to a widow who keeps bothering him. Jesus concludes, if an unjust judge will help a widow who keeps coming to him, how much more will God answer the prayers of those who keep praying! Parables often have a life application for the listener, and this one’s application is pray and not give up, as Luke explains.

Fencing the Torah

One of the things rabbis did were supposed to do, besides raise up many disciples, was to “build a fence around the Torah.” That meant to teach people how to observe God’s laws in the Torah by teaching them to stop before they get to the point of breaking one. Jesus did so in the Sermon on the Mount when he said,

You have heard that it was said to the people long ago, ‘Do not murder, and anyone who murders will be subject to judgment.’ But I tell you that anyone who is angry with his brother will be subject to judgment. (Matt 5:21)

In this verse Jesus is making a fence around the command “Do not murder” by giving the stricter command, “Do not even remain angry at your brother.” He does the same with adultery by saying that a person should not even look lustfully at a woman either.

One rabbi said that “Sin starts out as weak as a spider-web, but then becomes as strong as an iron chain.” This is the point of the fencing — if you don’t want to fall to sin, it is best to avoid the temptation at the earliest point.

Alluding to the Scriptures

Another method Jesus used was alluding, or hinting to, his scriptures. He would use a distinctive word or phrase from a passage in the Old Testament as a way of alluding to all of it.[3]

This was common in his time. In Medieval times this technique was called Remez. Even though Jesus wouldn’t have used that term, he often filled his sayings with references to the scriptures that would have been obvious to his biblically knowledgeable audience. For example, Jesus was probably alluding to a scene in 2 Chronicles 28:12-15 when he told the parable of the Good Samaritan. He would have expected his audience to remember the earlier story in order to interpret the later story.

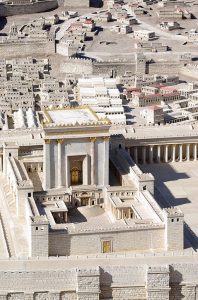

Sometimes, rabbinic teachers would hint to not just one scripture but two or more that shared a common word, and tie the two together in order to preach a message. Jesus did this when he said “My house is to be a house of prayer, but you have made it (my house) a den of thieves.” (Matt. 21:13) He is quoting both Isaiah 56 and Jeremiah 7 and tying them together, because they both contained the word beiti, “my house.” He is contrasting God’s greatest vision for the temple — Isaiah 56:7 describes all the nations of the world worshiping there — with the worst possible abuse of it, which was being used as a refuge for thieves and murderers, as in Jeremiah 7:11.

Physical examples in teaching

Along with stories that used images to teach, rabbis would frequently use situations to go along with their teaching. We know that Jesus washed his disciples feet. Another distinguished rabbi, Gamaliel, once got up and served his disciples at a banquet. When they asked him why he did such a humble deed he said,

Is Rabbi Gamaliel a lowly servant? He serves like a household servant, but there is one greater than him who serves. Consider Abraham who served his visitors. But there is one even greater than Abraham who serves. Consider the Holy One, blessed be he, who provides food for all his creation!

Abraham was the most revered of all of their ancestors, and Gamaliel reminds them of when God and two angels came to his tent in Genesis 18, that he prepared a meal and served it to them. Then he hints that God himself serves when he gives us our food.

Abraham was the most revered of all of their ancestors, and Gamaliel reminds them of when God and two angels came to his tent in Genesis 18, that he prepared a meal and served it to them. Then he hints that God himself serves when he gives us our food.

God himself is a model of serving others rather than wanting to be served. We can hear a little bit of a “Kal v’homer” saying, if one as great as God serves his lowly creation, certainly we can serve each other.

Jesus also uses visual lessons many times: for instance, when he called a child and had him stand there as he taught.

He called a little child and had him stand among them. And he said: “I tell you the truth, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me.” (Matt 18:2-5)

He uses the child as a concrete example to show the humility his followers must have, and the importance of not leading the innocent astray. Jesus may have used another example in this teaching as well: Capernaum was the center of production of millstones, and was right on the Sea of Galilee, and was where Jesus did much of his teaching. Jesus continues:

But if anyone causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him to have a large millstone hung around his neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea. (Matt 18:6)

When Jesus said this, he may have had his hand on an 800-pound basalt millstone as he gestured to his neck, and then to the Sea of Galilee!

Conclusion

Jesus used a method of teaching that is quite foreign to our culture, so it is easy to assume that his style was foreign to his first listeners too. We see instead that God was preparing a culture for his own coming, giving them a love for the scriptures and powerful techniques to teach the truth about him. Jesus used these methods to proclaim truth in an an uncommonly brilliant way. Certainly he was a master teacher.

~~~~

[1] For more, see chapter 12, “Jesus’ Bold Messianic Claims” in Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus, Baker Publishing, 2018. Much writing from this group can be found on the JerusalemPerspective.com website. See also, New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus: Insights from his Jewish Context, by David Bivin.

[2] See The Parables of the Sages (Jerusalem, Carta, 2015) by R. Steven Notley and Ze’ev Safrai.

[3] To explore Jesus’ use of allusion to his Scriptures, see chapter 3, “Stringing Pearls” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 36-50.

[3] To explore Jesus’ use of allusion to his Scriptures, see chapter 3, “Stringing Pearls” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 36-50.

Photos: James Tissot [Public domain], Serafima Lazarenko on Unsplash, duong chung on Unsplash