The first of the two great commandments, according to Jesus, is to love the Lord your God with all of your heart, soul and strength. A second one is like it — to love your neighbor as yourself (Matt 22:35-37). The overwhelming importance of this command is echoed in the rest of the New Testament. Peter says “above all, love one another” (1 Peter 4:8), and in the letters of John, that “this was the teaching you have heard from the very beginning – to love one another” (1 John 3:11).

While the incredible richness of the words “love your neighbor as yourself” is already apparent to us, hearing more about Jesus’ words in their Jewish context will deepen our understanding of this saying and link it to his other teachings.

The Link between Loving God and Your Neighbor

Just as the first of the two great commandments, to love the Lord, originates in the Old Testament (Deut. 6:5), the command to “love your neighbor” comes from there too. In Leviticus 19:18 it says,

You shall not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the sons of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself; I am the LORD.

Even before Jesus came on the scene, early rabbinic teachers had asked the question, “what is the great commandment of the Torah” and answered it by linking the two passages: “And you shall love the Lord your God with all of your heart, and all of your soul, and all of your strength,” and, “and/but you shall love your neighbor as yourself.“

Why? Because these two passages share the Hebrew word ve’ahavta, which means, “and you shall love.” This exact phrase is used only in these two Old Testament passages and one other place. The rabbis noticed that similar passages could be often interpreted together. The practice of connecting verses that share a unique or unusual word or phrase is called gezerah sheva.

They suggested that since both verses start with the command to love, that they could be understood together as if one was expanding on the other as an explanation of how to love. So the greatest commandment of the Law, the klal gadol ba Torah (great principle of the Torah) was to love your neighbor, by which you demonstrated your love for God.

Indeed, Paul and the other New Testament writers were echoing both Jesus and wider rabbinic thought when they said, “The entire law is summed up in a single command: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.'” (Gal. 5:14), or that loving your neighbor is the “royal law” (James 2:8).

Interpreting “Loving Your Neighbor As Yourself”

The commonly understood interpretation is that we should love others with the same measure that we love ourselves, which is certainly very true! But the rabbis also saw that the Hebrew of that verse can also be read as, “Love your neighbor who is like yourself.” While either interpretation is valid, their emphasis was less on comparing love of ourselves with love for others, and more on comparing other people to ourselves, and then loving them because they are like us in our own frailties.

This actually fits the original context of Lev. 19:18 better, “You shall not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the sons of your people, but you shall love your neighbor, as/like yourself; I am the LORD.” When we realize that we are guilty of the same sins that others are, we see that we shouldn’t bear grudges against them, but to forgive and love them instead.

The rabbis of Jesus’ day saw it as a challenge to realize that we are to love those who do not seem worthy because we ourselves are unworthy, and all are in need of God’s mercy. All people, including ourselves, are flawed and sinful, but we need to love them because we ourselves commit the same sins. One rabbi said,

If you hate your neighbor whose deeds are wicked like your own, I, the Lord, will punish you as your judge; and if you love your neighbor whose deeds are good like your own, I, the Lord, will be faithful to you and have mercy on you. (Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version B, chap. 26)

Another rabbi said:

Forgive your neighbor’s injustice; then, when you pray, your own sins will be forgiven. Should a person nourish anger against another, and expect healing from the Lord? Should a person refuse mercy to a man like himself, yet seek pardon for his own sins? (28:2-4) (Ben Sira, c. 180 B.C.)

While our traditional interpretation that we should love our neighbor as ourselves still remains true, the rabbis’ perspective highlights the fact that the time when we need to show love most is when we need to forgive the sins of others against us.

Now we can even hear the background of the verse of the Lord’s Prayer that says, “Forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us.” We could almost say, “Please love us even though we are sinners, as we love other sinners like ourselves.” Forgiving sins is one of the strongest tests of love — it is easy to love someone who has treated us rightly, but to love someone who has hurt us is far more difficult. God must love us greatly if he keeps forgiving the sins we commit against him!

Another thing that the rabbis would point out from the phrase “Love your neighbor who is like you,” is that all humans are made in the image of God, and all are precious to him, even the very worst of us. Every genocide starts with the idea that the enemy is not fully human. But if we remember that even the most wicked person bears the stamp of God’s image, we still must treat them justly and never forget their humanity.

Who is my neighbor?

In Luke 10, when Jesus is having a discussion with a lawyer about “loving your neighbor,” the lawyer asks him the question “And who is my neighbor?” We assume that this is not a legitimate question, but it actually was a very good question.

In Hebrew, the word reah was used for “neighbor,” but it was even more commonly used for “friend.” So the verse could be interpreted, “Love your friend who is like you” or “Love your friend as yourself,” which isn’t much of a challenge at all. The lawyer probably already understood that it didn’t just apply to one’s friends, it applied to one’s neighbors in a broader sense. The rabbinic debate was about how far that circle went, and he is asking Jesus just how far he thought that circle extended.

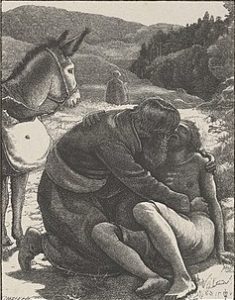

Jesus gave the lawyer a brilliant answer to how far the circle went: he told the parable of the Good Samaritan, and then asked the lawyer who was the neighbor to the dying man, which was the despised Samaritan (Luke 10). We would expect the answer to the question “Who is my neighbor” to be “the dying man.” But Jesus asked the question in such a way as to force the man to say that the neighbor was in fact, the Samaritan. In Jesus’ time the Samaritans and Jews despised each other as enemies, so Jesus’ implication is that we should go so far as to love even those who are not our friends.

Jesus gave the lawyer a brilliant answer to how far the circle went: he told the parable of the Good Samaritan, and then asked the lawyer who was the neighbor to the dying man, which was the despised Samaritan (Luke 10). We would expect the answer to the question “Who is my neighbor” to be “the dying man.” But Jesus asked the question in such a way as to force the man to say that the neighbor was in fact, the Samaritan. In Jesus’ time the Samaritans and Jews despised each other as enemies, so Jesus’ implication is that we should go so far as to love even those who are not our friends.

By telling this parable, it appears that Jesus brilliantly used rabbinic technique to elevate Leviticus 19:34, the third and final verse in the Old Testament that contains the word ve’ahavta, to the level of the other two.:

The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt; I am the LORD your God.

The Samaritan would have been the stranger and the alien among them, and Jesus shows that the stranger and alien was the neighbor that the man should love! It appears that Jesus is tying “Love your neighbor” with “love the stranger” and even “love your enemies”! This saying was utterly unique to Jesus, and while he built it on rabbinic thought of his time, it goes far beyond that. It is amazing to see how our rabbi Jesus began with this rich material and brought it to its pinnacle.

More light on the Samaritan

Jesus’ teaching grows even richer if the parable about the Good Samaritan in the light of a story in his scripture that his hearers would have recalled. (Remember that Jewish culture was very knowledgeable of their Scriptures, and rabbis frequently alluded to their scriptures to give more depth to their stories.)

In 2 Chronicles 28:8-15, a scene takes place after Israel is divided into the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Ahaz, the king of Judah, led the nation into terrible idolatry, even sacrificing children to idols. Because of this, the Lord let Judah be attacked and defeated by Israel. This is the first time that Israel actually took prisoners of the tribes of Judah.

The Israelites were on the verge of leading 200,000 Judean victims away as slaves when the prophet Oded chastised them by reminding them that God allowed them defeat Judah as a punishment for idolatry, and Israel was even more guilty of worshiping idols than their brothers. If they took their own brothers captive, it would compound their guilt before the Lord! The leaders of the Israelite tribes repented of their sin and set the Judeans free. The text says,

Then the men who were designated by name arose, took the captives, and they clothed all their naked ones from the spoil; and they gave them clothes and sandals, fed them and gave them drink, anointed them with oil, led all their feeble ones on donkeys, and brought them to Jericho, the city of palm trees, to their brothers; then they returned to Samaria. (2 Chron. 28:15)

We rarely read of a story of such compassion between nations at war, where one binds the wounds of the other and gently restores them to freedom. This was a remarkable moment of grace between the tribes of Israel.

These “good Samaritans” appear to be in the background of Jesus’ character of the Samaritan in his parable for several reasons. In the parable, Jesus mentions the town Jericho, one of the few times he ever mentions specific places in parables. The victim is stripped naked, like some of the Judeans were, and the Samaritan anoints the man and puts him on a donkey and carries him to Jericho, like was done with the Judeans. His audience easily could have brought to mind this story.

If Jesus had this in mind, it shows us even more brilliance packed into his parable. In this story of the ancient “good Samaritans”, the point at which they repented and decided to love their enemies was exactly when they became aware of the truth of Leviticus 19:18 — that their enemies were their own brothers, and that they were sinners just like them!

They were loving their neighbors, because they realized they were alike both in humanity and sinfulness. To the audience of Jesus’ parable, they would have remembered that the Samaritans actually did at one time do this act of great compassion for their enemies. And that they should act like these people (and love these people), who then were their worst enemies.

It is hard to overstate the depth and brilliance of Jesus in his rabbinic teaching. He builds on Old Testament stories and rabbinic thought to express an idea that was unique to him — that we should even love our enemies. Why? Because they are human beings, made in the image of God like ourselves, and because we are all sinners in God’s sight. Just as God loves both the just and the unjust, how much more, we who are sinners, should love other sinners like ourselves.

~~~~~

To explore this topic more, see chapter 4, “Meeting Myself Next Door” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 55-66.

To explore this topic more, see chapter 4, “Meeting Myself Next Door” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 55-66.

This essay is based in part on the following: “Jesus’ Jewish Command to Love” by Dr. Steven Notley at jerusalemperspective.com; and talks given by Dr. Randall Buth, “What be Commandment Big of the Law”, and by Dr. Steven Notley, “Do this and Live: The Ethics of Jesus.”

Photos: Eric T Gunther, “Arboretum neighborhood Washington DC.” Dalziel Brothers, “The Good Samaritan (The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ).”