by Lois Tverberg

Most of us see Noah and the flood and as a story for children. We may think of wallpaper for the baby’s room with cartoons of cute animals, arks and rainbows. Others focus on its historicity — how the large the ark was, where it landed, or what geological features might remain.

These traditional ways of looking at the flood story miss its deeper significance, and reflect the difficulty Western Christians have with the Eastern way of communicating theological truth. The Bible’s writers saw theology in history, and composed their stories with an eye toward the meaning behind the events.

Most of us tend to simply read for historical details and miss the greater implications of Old Testament stories, thinking that we can only find theology in the New Testament. Surprisingly, if we look at the flood again, we find that this ancient narrative gives a profound answer to the difficult question of how a good God can tolerate sin.1

The Story of Sin in Genesis

When we read the story of the Fall, we don’t have much problem seeing the theological implications when Eve chooses to overrule God to eat from the tree. We understand what it says about rebellion and sin, and how they separate us from God. We often overlook that fact that the problem of sin is actually an important theme of several early chapters in Genesis, and culminates in the story of the flood.

Almost immediately after the fall, we read about Cain’s murder of Abel. It is ironic that these two were the first brothers ever born, representatives of all of us as children of Adam and Eve, but when one ignored the fact that he was his “brother’s keeper,” he destroyed him.2

From Eve’s small act of rebellion by eating the apple, sin grew until it led to murder, claiming the life of one of her children. Later in that same chapter, sin grew even worse, when Cain’s descendant, Lamech, bragged to his family that as violent as Cain was, he was much worse! He said,

For I have killed a man for wounding me; and a boy for striking me; If Cain is avenged sevenfold, then Lamech seventy-sevenfold!”3 (Genesis 4:24)

The words of Lamech show that sin doesn’t stop at murder. He went even beyond, claiming the right to kill for the smallest of offenses. With that kind of attitude, we aren’t surprised that in the very next generation, sin had reached its climax and provoked a response from God:

“Then the LORD saw that the wickedness of man was great on the earth, and that every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. The LORD was sorry that He had made man on the earth, and He was grieved in His heart. The earth was corrupt in the sight of God, and the earth was filled with violence (hamas).”4 (Genesis 6:5-6, 11)

In these first chapters of Genesis we can see that over just a few generations sin had infected humanity so completely that it grieved the heart of God. It was a theological statement about the wickedness of mankind, contrasted with the goodness of God who had a short time before declared his creation “very good.”

We might wonder what human beings could do that would cause God such grief, but if we remember the horrors the Nazis committed in concentration camps, or the deaths of thousands in torture chambers in Iraq, or the mass graves found in many places in the world, we understand. Humans really are capable of wickedness beyond the limits of the imagination.

The Theological Problem

How can a good and sovereign God tolerate sin? This is a classic question, debated for millennia. Some say that evil shows God is either not powerful or not good by giving the following argument:

1. A good God would destroy evil.

2. An all powerful God could destroy evil.

3. Evil is not destroyed.

4.Therefore, there cannot possibly be a good and powerful God.

It is interesting that we usually pass by a profound answer to this difficult question that comes only a few chapters after the Bible’s beginning.

The flood does show that the first proposition is true: A good God would destroy evil. In the flood epic, we see a righteous God’s response to the depth of human wickedness. We usually miss the fact that the deluge was the most horrific act of judgment that the world had ever seen!

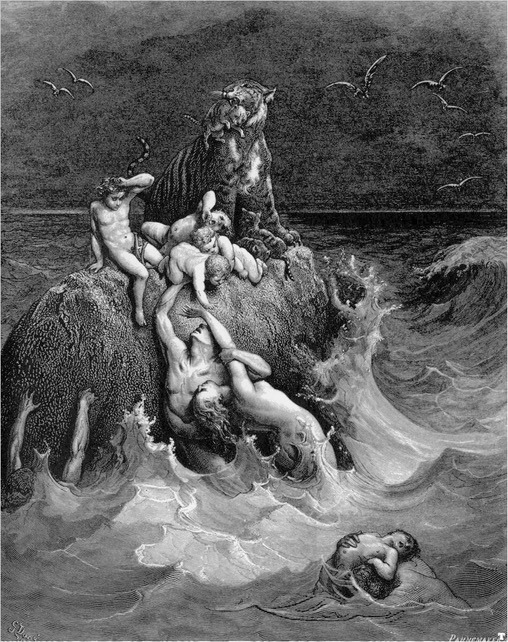

Rather than being a cute children’s story, the horror of the flood was captured in a woodcut by Gustave Dore that shows storm waves crashing around a rock where a man and woman are clinging, trying to save the lives of their children. It truly was an event that would have been utterly shocking to our sensibilities, a scene of incredible devastation.5

So philosophers are right that a good God would act to end evil on earth. The problem is in the second thesis, that an all powerful God could destroy evil. The flood proved that no amount of destruction of human life will destroy evil. Evil is part of man’s basic inclination now, and to eliminate it, God would be forced to destroy mankind itself. Our earth today is still filled with violence: we are no different than the generation that made God regret he had made us. Surprisingly, God now has a different response:

“Never again will I curse the ground because of man, even though every inclination of his heart is evil from childhood. And never again will I destroy all living creatures, as I have done.” (Genesis 8:21)

It is hard to see what had changed after the flood, because the evil within man didn’t change. Instead, God vowed to restrain himself against universal judgment, even if it is deserved. For much of the next passage, God established laws against the bloodshed that filled the earth, and declared that life is precious, especially that of humanity. Humans are unique because we are made in the image of God. Could this be why God decided not to send another flood? Is it that in spite of our sinfulness, by bearing his image, we are still precious in his sight?

The Covenant of the Bow

In light of this, the sign of the rainbow has a profound message for us. The Hebrew word for “rainbow,” keshet, is used for “bow” throughout the rest of Scripture. It was the weapon of battle. The covenantal sign of the rainbow says that God has laid down his “bow,” his weapon; and he has promised not to repeat the judgment of the flood, even if mankind does not change. It is because people are so precious to him that he has constrained himself to finding an answer to the problem of sin other than the obvious one of universal judgment.

In light of this, the sign of the rainbow has a profound message for us. The Hebrew word for “rainbow,” keshet, is used for “bow” throughout the rest of Scripture. It was the weapon of battle. The covenantal sign of the rainbow says that God has laid down his “bow,” his weapon; and he has promised not to repeat the judgment of the flood, even if mankind does not change. It is because people are so precious to him that he has constrained himself to finding an answer to the problem of sin other than the obvious one of universal judgment.

Throughout the rest of the Bible, whenever God made a covenant, it was of monumental importance in his plan for the salvation of the world. The covenants with Abraham, with Israel on Mt. Sinai, and with King David to send the Messiah were all key events in salvation history.

We should realize that the covenant with Noah is just as important, because in it he promises to find another way to deal with the problem of sin than just to destroy sinners. It is the most basic covenant of all: to promise to find a way to redeem humanity from evil rather than just to judge it for its sin.

We know that Jesus promised to return to judge, so the day of reckoning is coming, but God sent Christ so that as many as possible could find his atonement before that time, so that God could show as much mercy as possible to the earth. His slowness to judge is not out of impotence, but out of his great mercy. As Peter says,

Long ago by God’s word the heavens existed and the earth was formed out of water and by water. By these waters also the world of that time was deluged and destroyed. By the same word the present heavens and earth are reserved for fire, being kept for the day of judgment and destruction of ungodly men. But do not forget this one thing, dear friends: With the Lord a day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years are like a day. The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. He is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance. (2 Peter 3:4-9)

Now we have a different way of looking at that classic debate, perhaps the way God sees it:

1. God is good and is able destroy all evil.

2. But in doing so, he would destroy humanity, which is precious to Him.

3. Evil is not destroyed.

4. God is infinitely good and powerful, but out of mercy, chooses to wait to judge. In response to sin, he sent his Son as an atonement for all who would receive him.

Even in this story at the very beginning of the Bible, we can see God’s ultimate desire for mercy rather than punishment for sin. He will finally bring it to maturity in Christ, who will extend a permanent covenant of peace with God through his atoning blood.

~~~~

1 See also Listening to the Language of the Bible, pp 51-52, available in the En-Gedi bookstore.

2 Ibid, pp 77-78.

3 Jesus may have been referring to Lamech in his teachings on being the opposite — seeking forgiveness instead of revenge. See “Lamech’s Opposite.“

4 It says something that the terrorist organization Hamas chose to name itself for the Hebrew word for “violence,” hamas, the very thing that grieved God’s heart so much that he regretted making humanity.

5 In September 2001, our Bible study was discussing the story of Noah. Our first response was why God didn’t just destroy the terrorists of 9/11 before they acted. From this story, we realized that no amount of destruction of evil human beings would rid us of the problem of evil in mankind.

Photos: Simon de Myle [Public domain], Gustave Doré [Public domain], Yulia Gadalina on Unsplash

God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers.

God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers. When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4

When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4