Do not judge so that you will not be judged. For in the way you judge, you will be judged; and by your standard of measure, it will be measured to you. Matthew 7:1-2

What did Jesus mean by “do not judge?” This is one of those sayings of Jesus that can be unclear. It can sound like Jesus was telling us to look the other way when we see sin. However, from everything else that Jesus said, we know that he couldn’t be suggesting this. Yet, to not be guilty of ” judging,” we often try to avoid calling sin for what it is.

To better understand what Jesus meant, it is helpful to study some of the discussion going on among others in Jesus’ culture and see if they can shed light on his words. Interestingly, Jesus’ contemporaries taught ideas close to this concept of “do not judge.” While their words do not have the authority of Jesus’ words, and while we need to be discerning about our conclusions, we will see that Jesus may have been expanding on their good ideas in his own teaching about judging.

Judging Others Favorably

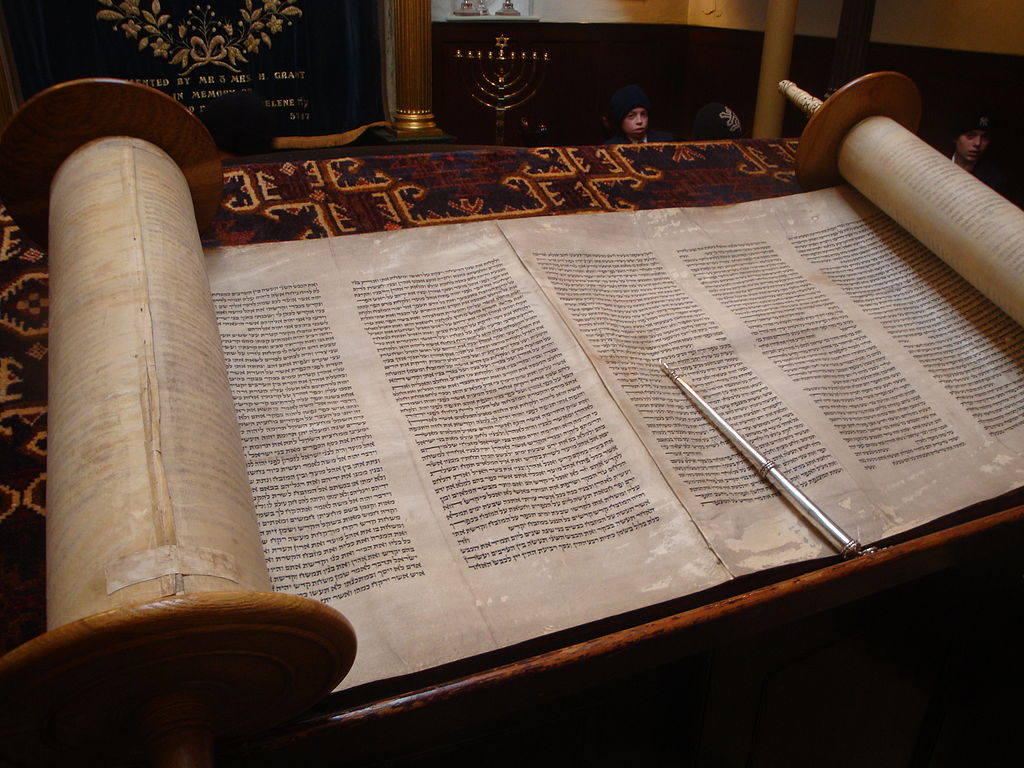

We can find some of discussion of Jesus’ contemporaries recorded in the Mishnah. The Mishnah is a collection of Jewish sayings written about two hundred years after Jesus lived, but including teachings from his time and before. The most important reference was from a rabbi who lived more than a hundred years before Jesus who said, “Judge everyone with the scales weighted in their favor” (Yehoshua ben Perechia, Avot 1:6).  In a later source, the Babylonian Talmud, it says “He who judges his neighbor favorably will be judged favorably by God” (Shabbat 127a). It is interesting to see how reminiscent this is of Jesus’ saying, “with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” To “judge in favorable terms” was considered as important as visiting the sick, devotion in prayer, or teaching the Scriptures to your children!

In a later source, the Babylonian Talmud, it says “He who judges his neighbor favorably will be judged favorably by God” (Shabbat 127a). It is interesting to see how reminiscent this is of Jesus’ saying, “with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” To “judge in favorable terms” was considered as important as visiting the sick, devotion in prayer, or teaching the Scriptures to your children!

A story was told to illustrate the point:

A man went to work on a farm for three years. At the end of this time, he went to his employer and requested his wages so that he could go home and support his wife and children. The farm owner said to him, “I have no money to give you!”

So he said to him, “Well, give me some of the crops I’ve helped grow.”

The man replied, “I have none!”

“Well then, give me some of the goats or sheep, that I’ve helped to raise!”

And the farmer shrugged and said that he had nothing he could give him. So the farm hand gathered up his belongings and went home with a sorrowful heart.

A few days later his employer came to his house with all of his wages along with three carts full of food and drink. They had dinner together and afterward the farm owner said to him, “When I told you I had no money, what did you suspect me of?”

“I thought you had seen a good bargain and used all your cash to buy it.”

Then he said “What did you think when I said that I had no crops?”

“I thought perhaps they were all leased from others.”

He then said, “What did you think when I said I had no animals?”

“I thought that you may have dedicated them all to the Temple.”

The farmer answered him, “You are right! My son wouldn’t study the Scriptures, and I had rashly vowed all of my possessions to God in my prayers for my son. But, just a couple days ago, I was absolved of the vow so that now I can pay you. And as for you, just as you have judged me favorably, may the Lord judge you favorably!” 1

This story is a strong example of resisting condemnation. It also parallels, “For with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” Could this enlighten us to the gist of what Jesus was saying? In the story, the hired hand always gave the employer the benefit of the doubt by imagining the best possible motivation for his seemingly suspicious actions. This is exactly what the rabbis meant by always judging a neighbor favorably.

This seems like a nice thought, but hardly an earth-shaking interpretation of Jesus’ words. But, what if we applied it to our own lives? Just imagine these situations and the choices you might have in your reactions:

On the way to church, a car passes you on the road and cuts you off. Why?

– The driver is has no regard for speed laws! He is just trying to impress people!

– or, maybe the driver is late for something, or his kids are driving him crazy.

In church, you are asked to greet the people around you, but the lady in front of you was obviously avoiding you. Why?

– She is obviously a snob and you didn’t dress well enough today!

– or, maybe she is new to this church or uncomfortable meeting people.

A woman asks you afterward about the surgery she had heard that you had. Why?

– She is a busybody who just wants to put her nose in your business!

– or, maybe she genuinely worries about others, and wants to share your burdens.

In almost every situation, we have the choice to look for a good motivation or a bad motivation behind other people’s behavior. The way we interpret others’ motivations has a profound effect on our reactions toward others. This idea of the rabbis to “judge favorably” certainly was a great one, even if it isn’t exactly what Jesus said.

A Worship War

Imagine another scenario where a “worship war” has broken out in a congregation. The older members want to sing hymns and the young members want gospel rock. The older people are saying things like, “They have no appreciation for the richness of hymns – they only want to be entertained!” The younger people respond with, “The old folks don’t care about reaching the lost—they just want to do things the same old way!”

What would happen if each group stopped assigning negative motivations to the other group? What if the “hymns only” group started saying, “Maybe the younger members of our church think that they can bring new meaning to the service by putting it in their own style…” What if the “rock band” enthusiasts started saying, “Maybe the older members find more meaning in what’s familiar rather than in what sounds strange to them…”

What would happen if each group stopped assigning negative motivations to the other group? What if the “hymns only” group started saying, “Maybe the younger members of our church think that they can bring new meaning to the service by putting it in their own style…” What if the “rock band” enthusiasts started saying, “Maybe the older members find more meaning in what’s familiar rather than in what sounds strange to them…”

How long would the conflict last in that church? How long would it be before both groups would try their best to love and accommodate each other?

To this day, Jewish culture has endeavored to instill in its people the ethic to “judge favorably.” There’s a Jewish group that meets simply to practice giving the benefit of the doubt when it appears someone has done something unkind. They reflect on hurts in their lives and then propose ways to excuse the perpetrator. When one of them didn’t receive an invitation to a wedding, they would say, “Perhaps the person was under the impression that they had already sent an invitation,” or, “Perhaps they couldn’t afford to invite many people.” 2

One Jewish website called, “The Other Side of the Story” is filled with stories where a person looked liked he was in the wrong, but then turned out to be innocent.4 The point is simply to teach others the importance of judging favorably.

Jesus’ Words, “Do Not Judge”

Even though the rabbis’ words are wise, they aren’t exactly what Jesus said. How does Jesus teaching about “do not judge” compare to theirs? Jesus began with what the other rabbis taught and then increased the challenge. His audience already knew about the “judge favorably” teaching; it had been around for at least a hundred years. The famous rabbi Hillel, who lived fifty years before Jesus, said, “Judge not your fellow man until you yourself come into his place” (Avot 2:5). His idea was that we shouldn’t judge because we don’t have full knowledge of another’s life experience. We can’t know if someone struggles with depression or some other wound from their past. Hillel’s idea is a step closer to what Jesus said, and it shows that the discussion of “judging” was still going on in Jesus’ time.

However, Jesus’ reasoning was different from Hillel’s. Jesus knew that people sometimes do sin willfully and intentionally. At some point it will be undeniable that a person’s intention was evil, and we can’t pretend that it wasn’t. Jesus pointed out that our response must be to remind ourselves of our own sinful hearts—the only hearts we really can know. Realizing our own sinful nature, we shouldn’t place judgment on others. If we want God to be merciful to us, we need to put aside condemnation and extend mercy instead.

As Jesus said, “Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. Do not judge, and you will not be judged. Do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven…For with the measure you use, it will be measured out to you.” (Luke 6:35-38) Rather than saying, “Judge favorably,” perhaps Jesus would have said, “Judge mercifully! Do everything you can to extend mercy to others.”

Obviously, this not to cast aside discernment. We should discern whether an action or an outward attitude is wrong. According to Paul, the church is not only to discern, but also obligated to discipline sinful practice among its members (1 Cor. 5:1-5). And when a wrong is committed against us personally, Jesus tells us to show the person his sin in hopes of his being repentant so that we can forgive (Matt 18:15-17).

While we can discern sin in practice, only God knows the motive of the heart. We need to leave final judgment up to him. To judge another is to presume to have both the knowledge and authority of God himself. So when we are in a situation where we are tempted to condemn someone, we need to step back, hand the situation over to the Lord, and remind ourselves that it is his job to render judgement, not ours. As we read in James 4:12, “There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the One who is able to save and to destroy; but who are you who judge your neighbor?”

While we can discern sin in practice, only God knows the motive of the heart. We need to leave final judgment up to him. To judge another is to presume to have both the knowledge and authority of God himself. So when we are in a situation where we are tempted to condemn someone, we need to step back, hand the situation over to the Lord, and remind ourselves that it is his job to render judgement, not ours. As we read in James 4:12, “There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the One who is able to save and to destroy; but who are you who judge your neighbor?”

It turns out that both the rabbis’ words and Jesus’ words are extremely useful in every day life. Our attitude toward others will become more loving when we assume the best rather than the worst about people. If we try to always “judge favorably,” we will be less likely to have a critical or cynical spirit towards others. Even when people are clearly in the wrong, we can give them the benefit of the doubt as much as possible.

Other Ways of Judging

If judging (or judging negatively) is defined as believing the worst about others, it includes many other types of hurtful behavior as well. Insults are a form of judgment, such as calling someone arrogant or loud-mouthed. Gossip relies heavily on judgment too. People who gossip usually look for wrongdoing in a person’s life in order to share it with others. Criticism, cynicism, even complaining are all rooted in searching out the negative everywhere we can find it. James says, “Do not speak against one another, brethren. He who speaks against a brother judges his brother” (James 4:11).

Negative judgments are particularly toxic to marriage relationships. In the book Blink,3 Malcolm Gladwell describes a study of married couples which examined the rate of divorce compared to attitudes that the couple showed toward each other in interviews five or ten years earlier. The interviewers looked at dozens of variables, but found only one factor that could almost surely predict divorce—an attitude of contempt. When one or both partners habitually spoke to the other with disdain or disgust, even in the most subtle ways, the marriage was often moving toward a break up. If you think about it, contempt comes from a history of judging unfavorably and without mercy. It is a way of saying, “I have reached my verdict, and there is nothing good in you.”

People who struggle with chronic anger can often find the root of their problem in looking for something wrong in other peoples’ actions—their own act of judging negatively. If you think about it, anger always involves an accusation of sin. Next time you are angry, ask yourself what sin you might be accusing the other person of; then remember that Jesus says that you are a sinner too. You can’t expect God’s mercy if you aren’t merciful to others. (See Matthew 18:23-34.)

Summary

All of us would do well to focus more on judging favorably, and extending mercy. Both are ways of showing God’s grace. We’ll find that over time, it really has the potential to transform our personalities to be more like Christ. Listen to Jesus words one more time:

Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. Do not judge, and you will not be judged. Do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven. Give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together and running over, will be poured into your lap. For with the measure you use, it will be measured to you. Luke 6:35-38

~~~~~

To explore this topic more, see chapter 8, “Taking My Thumb off the Scale” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 104-16.

To explore this topic more, see chapter 8, “Taking My Thumb off the Scale” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 104-16.

1 B. Talmud, Shabbat 127a

2 J. Telushkin, The Book of Jewish Values, (c) 2000, Bell Tower, New York, ISBN 0609603302, p. 35.

3 M. Gladwell, Blink (c) 2005, Little, Brown & Co, New York, ISBN 9780316172325, pp. 30-34.

Photos: John Salvino and Wesley Tingey on Unsplash; Louis Smith on Unsplash; http://ferxtreme.hu/wp-content/uploads/birosag.jpg

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us). Why would torah be translated as law? Because when God instructs his people how to live, he does it with great authority. His torah demands obedience, so the word takes on the sense of “law.” But in Jewish parlance, torah has a very positive sense, that our loving Creator would teach us how to live. It was a joy and privilege to teach others how to live life by God’s instructions. This was the goal of every rabbi, including Jesus.

Why would torah be translated as law? Because when God instructs his people how to live, he does it with great authority. His torah demands obedience, so the word takes on the sense of “law.” But in Jewish parlance, torah has a very positive sense, that our loving Creator would teach us how to live. It was a joy and privilege to teach others how to live life by God’s instructions. This was the goal of every rabbi, including Jesus.

In a later source, the Babylonian Talmud, it says “He who judges his neighbor favorably will be judged favorably by God” (Shabbat 127a). It is interesting to see how reminiscent this is of Jesus’ saying, “with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” To “judge in favorable terms” was considered as important as visiting the sick, devotion in prayer, or teaching the Scriptures to your children!

In a later source, the Babylonian Talmud, it says “He who judges his neighbor favorably will be judged favorably by God” (Shabbat 127a). It is interesting to see how reminiscent this is of Jesus’ saying, “with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” To “judge in favorable terms” was considered as important as visiting the sick, devotion in prayer, or teaching the Scriptures to your children! What would happen if each group stopped assigning negative motivations to the other group? What if the “hymns only” group started saying, “Maybe the younger members of our church think that they can bring new meaning to the service by putting it in their own style…” What if the “rock band” enthusiasts started saying, “Maybe the older members find more meaning in what’s familiar rather than in what sounds strange to them…”

What would happen if each group stopped assigning negative motivations to the other group? What if the “hymns only” group started saying, “Maybe the younger members of our church think that they can bring new meaning to the service by putting it in their own style…” What if the “rock band” enthusiasts started saying, “Maybe the older members find more meaning in what’s familiar rather than in what sounds strange to them…” While we can discern sin in practice, only God knows the motive of the heart. We need to leave final judgment up to him. To judge another is to presume to have both the knowledge and authority of God himself. So when we are in a situation where we are tempted to condemn someone, we need to step back, hand the situation over to the Lord, and remind ourselves that it is his job to render judgement, not ours. As we read in James 4:12, “There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the One who is able to save and to destroy; but who are you who judge your neighbor?”

While we can discern sin in practice, only God knows the motive of the heart. We need to leave final judgment up to him. To judge another is to presume to have both the knowledge and authority of God himself. So when we are in a situation where we are tempted to condemn someone, we need to step back, hand the situation over to the Lord, and remind ourselves that it is his job to render judgement, not ours. As we read in James 4:12, “There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the One who is able to save and to destroy; but who are you who judge your neighbor?”