by Lois Tverberg

Which of you, if he has a hundred sheep and loses one of them, would not leave the ninety-nine in open pasture and go and look for the one that was lost until he finds it? Then when he has found it, he places it on his shoulders, rejoicing….(Luke 15:4-7)

Interestingly, Jesus wasn’t the only rabbi to tell parables about shepherds looking for sheep. Another person said,

When a sheep strays from the pasture, who seeks whom? Does the sheep seek the shepherd, or the shepherd seek the sheep? Obviously, the shepherd seeks the sheep. In the same way, the Holy One, blessed be He, looks for the lost.(1)

Both Jesus’ words in Luke 15 (above) and this parable are about repentance. Jesus talks about God having joy at repentance, and this other rabbinic parable says even that when a person repents, ultimately it was God who caused it to happen. It is interesting that even other rabbis had the understanding that God has mercy on the lost, and pursues them to bring them back to himself.

Both Jesus’ words in Luke 15 (above) and this parable are about repentance. Jesus talks about God having joy at repentance, and this other rabbinic parable says even that when a person repents, ultimately it was God who caused it to happen. It is interesting that even other rabbis had the understanding that God has mercy on the lost, and pursues them to bring them back to himself.

How did the idea of repentance become linked together with the image of a shepherd finding his sheep? It likely came from a very important passage very early in the Scriptures, at the culmination of Deuteronomy, right after God had given his covenant. God gave grave warnings of all the terrible curses that will happen to Israel if they forsake him, the worst of which that they will be scattered as a people – the dissolving of the nation itself. But then, after all of that, he promises:

When all these blessings and curses I have set before you come upon you and you take them to heart wherever the LORD your God disperses you among the nations, and when you and your children return to the LORD your God and obey him with all your heart and with all your soul according to everything I command you today, then the LORD your God will restore your fortunes and have compassion on you and gather you again from all the nations where he scattered you. Even if you have been banished to the most distant land under the heavens, from there the LORD your God will gather you and bring you back. He will bring you to the land that belonged to your fathers, and you will take possession of it. He will make you more prosperous and numerous than your fathers. The LORD your God will circumcise your hearts and the hearts of your descendants, so that you may love him with all your heart and with all your soul, and live. (Deut. 30:1-6)

People understood this promise was not just one of being brought back together physically, but more importantly that God would bring them back to himself spiritually – that he would give them a new heart to love himself. If they just started to repent, God would do the rest in terms of restoring their relationship.

Jeremiah reiterates this promise in chapter 31, when he speaks of the future hope for Israel:

“Hear the word of the LORD, O nations; proclaim it in distant coastlands: `He who scattered Israel will gather them and will watch over his flock like a shepherd.’ … “The time is coming,” declares the LORD, “when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah. It will not be like the covenant I made with their forefathers when I took them by the hand to lead them out of Egypt, because they broke my covenant, though I was a husband to them,” declares the LORD. “This is the covenant I will make with the house of Israel after that time,” declares the LORD. “I will put my law in their minds and write it on their hearts. I will be their God, and they will be my people. No longer will a man teach his neighbor, or a man his brother, saying, `Know the LORD,’ because they will all know me, from the least of them to the greatest,” declares the LORD. “For I will forgive their wickedness and will remember their sins no more.” (Jeremiah 31:10, 31-34)

Both of these passages would have been central to the messianic hope of the people in Jesus’ day. They knew that their nation was in desperate need of redemption, both physically from the Romans, and spiritually from their sins. They longed for God to send the “shepherd” messiah who would give them all a new heart to obey God, making a new covenant with his people for an intimate relationship together.

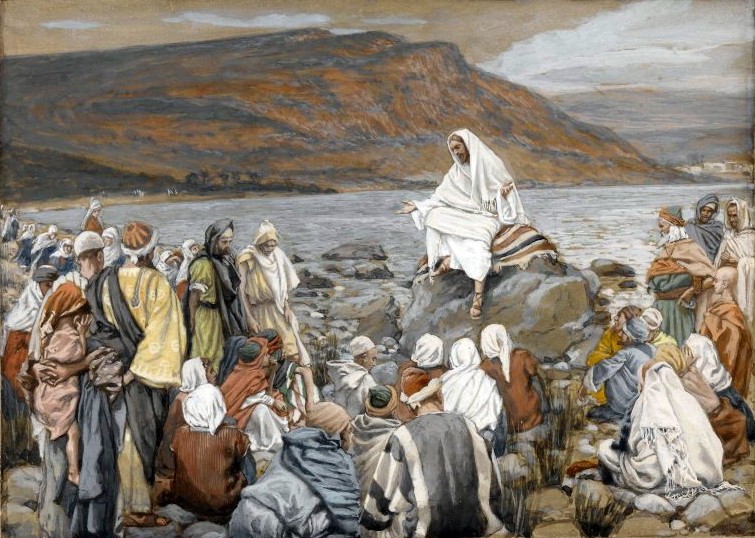

Now we see why Jesus so frequently uses imagery of a shepherd to describe himself, and why at the Last Supper he speaks about a “new covenant for the forgiveness of sins.” He is saying that he himself is the fulfillment of God’s promise from the very beginning to forgive his people of their sins, and to give them his Spirit and new hearts to follow him.

(1) B. Young, The Parables: Jewish Tradition and Christian Interpretation, p 192. © 1998, Hendrickson. ISBN 1-56563-244-2. Also, see B. Young, Jesus the Jewish Theologian, © 1995, Hendrickson. ISBN: 0-80280-423-3. Both books are available at En-Gedi’s bookstore.

Photo: http://pixdaus.com/the-shepherd-and-his-sheep-in-a-beautiful-path-through-the-t/items/view/568897/