by Lois Tverberg

Many of us have seen the movie Narnia or read the classic book, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. This classic tale contains obvious parallels to the story of Christ. At the climax, the White Witch demands the life of the boy Edmund because he is a traitor to his family. She says that the “deep magic” allows her to kill every traitor — his life is forfeit for his sin.

Many of us have seen the movie Narnia or read the classic book, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. This classic tale contains obvious parallels to the story of Christ. At the climax, the White Witch demands the life of the boy Edmund because he is a traitor to his family. She says that the “deep magic” allows her to kill every traitor — his life is forfeit for his sin.

Aslan, the Lion who represents Christ, gives his life in the boy’s place but later rises from the dead. When asked why, he said, “…there is a magic deeper still which [the White Witch] did not know … that when a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Table [of judgment] would crack and Death itself would start working backward.”1

This “deeper magic” of Narnia — the idea that the sins of one person can be forgiven because of another person’s sacrifice — is a fundamental part of the Christian understanding of substitutionary atonement. We take it for granted that mercy is shown to the guilty for the sake of an innocent person.

If you think about it, this is quite illogical. In our own relationships we generally don’t transfer our feelings from one person to another. We don’t say “thank you” to one person because someone else did us a favor. Somehow, however, we have gotten used to the idea that God will forgive many sinners because of the righteousness of just one person.

Does the idea of granting mercy for the sake of another have precedent in the Hebrew scriptures? One might think it was invented in the New Testament. But interestingly, according to Jewish scholars, the answer is yes. Many have found this merciful “divine illogic” throughout the Old Testament and consider it an important principle of Judaism!

Jewish scholars explore the most minute details of the Torah and Hebrew scriptures, often picking up subtle themes that Christians might miss. So it is fascinating to see all the motifs that they find even though they may not be looking for Jesus.

Mercy for the Sake of Another

The Jewish scholar Nahum Sarna sees this pattern as early as Genesis 19, when Lot was saved from the destruction of Sodom. Lot had chosen to move to Sodom knowing that it was sinful. He became active in city leadership and even allowed his daughters to intermarry with the population.

The Jewish scholar Nahum Sarna sees this pattern as early as Genesis 19, when Lot was saved from the destruction of Sodom. Lot had chosen to move to Sodom knowing that it was sinful. He became active in city leadership and even allowed his daughters to intermarry with the population.

Even though Lot wasn’t as corrupt as the Sodomites, God did not save him because of his own righteousness. Rather, the Bible says that “God was mindful of Abraham and removed Lot from the midst of the upheaval” (Gen 19:29). God delivered Lot from the catastrophe for the sake of Abraham — as a response to Abraham’s faithfulness, not Lot’s.

According to Sarna, “This ‘doctrine of merit’ is a not an infrequent theme in the Bible and constitutes many such incidents in which the righteousness of chosen individuals may sustain other individuals or even an entire group through its protective power.”2

This is the first of many times when God pardons one for the sake of another. For some strange reason, God often made his forgiveness contingent on an intercessor’s prayer. For instance, when King Abimelech took Abraham’s wife Sarah captive, God told him that he was under judgment, but if Abraham prayed for him, he would live (Gen. 20:7). At one point, God even lamented that no one can be found to “stand in the gap” for his people, as if he will not act without an intercessor (Ezekiel 22:30).3

Similarly, at the end of the story of Job, God was furious with Job’s counselors and said to them, “I am angry with you and your two friends, because you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has. … My servant Job will pray for you, and I will accept his prayer and not deal with you according to your folly” (Job 42:7-8).

God’s forgiveness seems to await the request from Job, the innocent victim of their sin. Moreover, the fact that God calls him “my servant” is a compliment that was rarely used except for those whom God highly esteemed.4 Was God saying that in accepting his prayer, he will pardon them for Job’s sake, rather than their own?

The Merit of the Fathers

A related idea in Judaism is that God will show special mercy toward the people of Israel because of the merits of their forefathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.5 They see this as coming from God’s promises of blessing to the patriarchs, and because he told Moses that he would pardon to the thousandth generation those who love him (Ex. 34:6-7).

So when Moses appealed to God to forgive Israel in the wilderness, he reminded him of his promise to his ancestors (Ex. 32:13, Deut. 9:27). In Micah 7 and elsewhere, God’s mercy is linked to his pledge to the patriarchs:

Who is a God like you, who pardons sin and forgives the transgression of the remnant of his inheritance? You do not stay angry forever but delight to show mercy. You will again have compassion on us; you will tread our sins underfoot and hurl all our iniquities into the depths of the sea. You will be true to Jacob, and show mercy to Abraham, as you pledged on oath to our fathers in days long ago. (Micah 7:18-20)

Even Paul alluded to this idea in Romans 11:28: “… but as far as election is concerned, they are loved on account of the patriarchs, for God’s gifts and his call are irrevocable.” John the Baptist, however, told his audience to repent and to not assume that the merit of their ancestors would be sufficient to pay for their sin: “Do not think you can say to yourselves, `We have Abraham as our father.’ I tell you that out of these stones God can raise up children for Abraham” (Matt 3:9).6

Because of this idea, when Jews pray for forgiveness for their sins on Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur, they focus on reminding God of the faithfulness of their ancestors, focusing especially on the story of the “Akedah,” when Abraham was willing to sacrifice Isaac at God’s request.

It is ironic that they ask for forgiveness for the sake of Abraham, who was a father who had such great love for God that he was willing to sacrifice his own son. Even more ironic is the fact that they also ask for mercy for the sake of Isaac, who offered himself up as a willing sacrifice and was obedient to do his fathers will! (The rabbis noted that if Isaac was carrying enough wood to burn a sacrifice, he had to be a grown man and able to overpower his elderly father. They saw his willingness to be a sacrifice as the major point of the story.)

While these practices are not explicitly pointing toward Christ, they do show that the Jewish reading of the Hebrew Bible supports the idea that a sinner can seek forgiveness from God because of the righteous merits of another person.

Atonement for Unintentional Murder

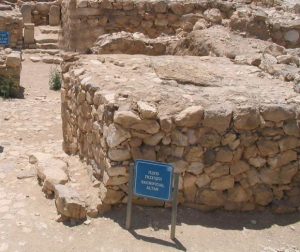

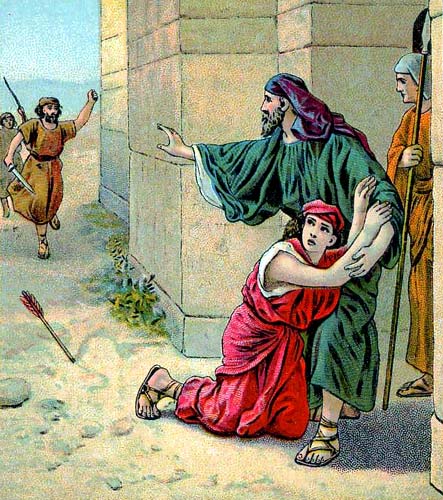

Another interesting place Jewish sources have found themes that Christians would see as pointing to Christ is in the regulations involving cities of refuge. Those cities were to be places where people guilty of accidental manslaughter could flee to escape revenge by the offended family (Numbers 35:9-15, 22-28).

Another interesting place Jewish sources have found themes that Christians would see as pointing to Christ is in the regulations involving cities of refuge. Those cities were to be places where people guilty of accidental manslaughter could flee to escape revenge by the offended family (Numbers 35:9-15, 22-28).

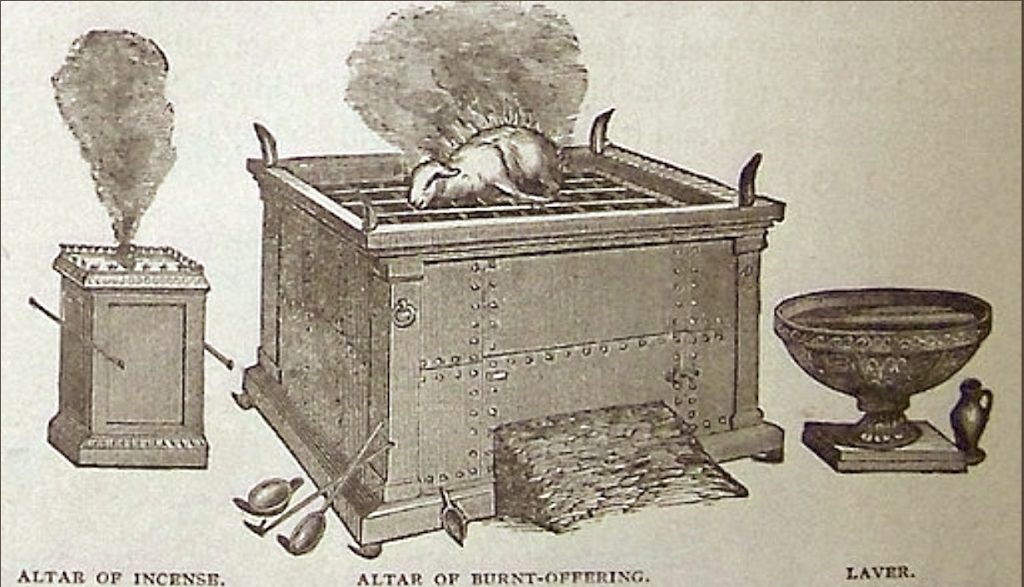

Guilty individuals were required to live in the city until the death of the High Priest, at which time they were free to go home. The rabbis had a fascinating interpretation of the logic behind this:

The priests atone for unintentional sins through the offering of sacrifices, the high priest atones for even more, this being the reason for his functions on Yom Kippur, and the death of the high priest is the highest form of atonement which atones for unintentional manslaughter, the severest of unintentional sins. 7 (emphasis mine)

Remarkably, in the subtle logic of Torah regulations that Christians tend not to read, we see a picture of Christ as our great High Priest who obtained forgiveness for our sins through his own death.

Seeing the Merciful Illogic of Christ’s Atonement

Jesus’ first followers were well acquainted with the Hebrew Scriptures and their interpretation. They certainly knew Isaiah 53, that spoke of one who would “bear the sin of many, and make intercession for the transgressors” (Is. 53:12). They did not invent the idea that Jesus’ sacrifice would atone for the sins of those who believed in him; rather, they could see that it was woven throughout their Scriptures from beginning to end.

~~~~

1 The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C. S. Lewis (New York, MacMillan, 1950)

2 See Understanding Genesis by Nahum Sarna (New York: Shocken Books, 1966), p. 150-151.

3 Ibid.

4 JPS Torah Commentary on Genesis, by Nahum Sarna p. 187.

5 S. Schechter, Aspects of Rabbinic Theology, pp. 170 – 198. Also, see “Virtue, Original,” by Joseph Jacobs

6 Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of the Tannaim, by G.F. Moore, (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1927), pp. 535-545.

7 Rabbi Shmuel David Luzzatto (1800–1865), as quoted (without a source) in “Parashat Matot-Masei” by Zvi Shimon, Yeshivat Har Etzion’s Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash

Photos: Chris Bair on Unsplash, Benjamin West [Public domain], the Providence Lithograph Company [Public domain]