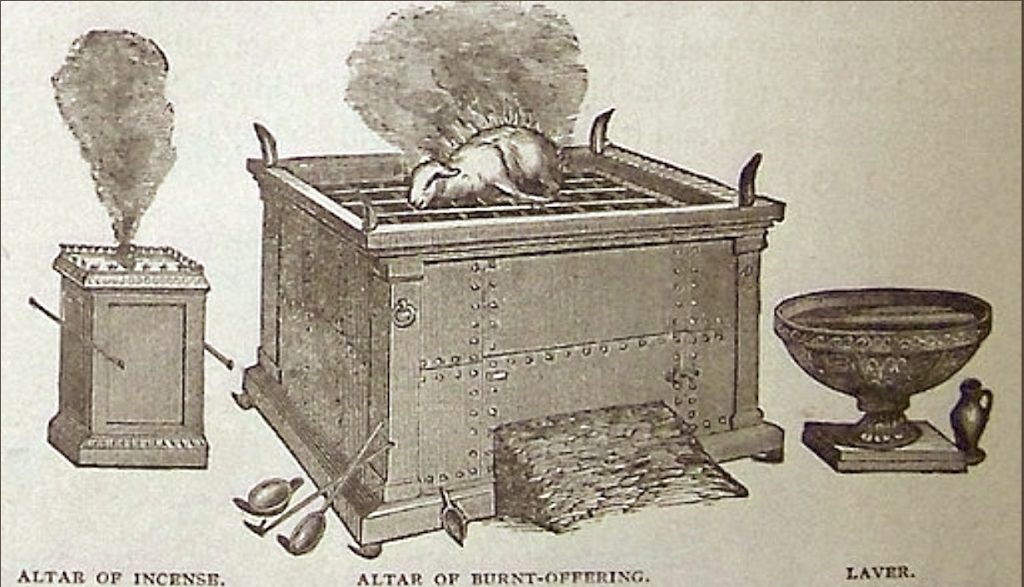

There is probably nothing in the Bible so incomprehensible to modern Christians as the use of sacrifice in the Old Testament for the worship of God. We struggle with its bloody imagery. Why did God require it? How could people find it meaningful?

Surprisingly, even the New Testament views sacrifice in a positive light. Even after Jesus’ death, Paul and the early church continued to take part in the sacrifices at the Temple. Paul often spoke of them as a beautiful thing, expecting us to understand when he speaks about us as being “living sacrifices” (Rom. 12:1). Paul also writes,

Walk in love, just as Christ also loved you and gave himself up for us, an offering and a sacrifice to God as a fragrant aroma. Ephesians 5:2

What does all of this strange imagery mean?

Ancient Thinking and God’s Instructions

The idea of sacrifice was not something that first originated in the Bible — it was familiar throughout the ancient world. God often spoke to his people in customs they already understood, but then modified them to say something different about himself.

Polytheists in the Ancient Near East believed that by making idols, they were making a bodily form for their god to inhabit, and when they put them in temples, they were giving them a home to live in. By furnishing the god’s home lavishly and bringing them the finest of foods as sacrifices, the god could be petitioned for favors.

The ancients also believed that the world was the property of the gods, and since the gods controlled all fertility, a person must always offer some of the harvest back to them. A planted field was sacred and off-limits until its first crops were given to the god, and all firstborn animals were the property of the gods too. If a person killed an animal, he was obligated to give an offering from the animal to pay the gods for its life.1 Because a person’s life depended on fertility of the soil and of animals, it was imperative to honor the gods in this way.

When God gave his people instructions for worship, he used these cultural ideas to teach them about himself. Because God is the true creator of the universe, and the “earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof,” (Ex. 9:29, Ps. 24:1) it was appropriate that the Israelites brought their harvest offerings to him. He was the one who gave their animals and fields fertility, not the idols that their neighbors worshipped.

God also told them to make a tabernacle, saying, “Have them make a sanctuary for me, and I will dwell among them” (Ex. 25:8). Interestingly, God’s goal was not to dwell in it, but to dwell among them. He wanted to have intimacy with his people, and for them to know how near he was.

However, God was emphatic that no idols should be carved, because he is incomprehensible and utterly unlike all of the “gods” that others had been worshipping. He was using their understanding to tell them that while he desired a close relationship with his people, he was utterly unlike anything they had ever known before.

Sacrifices for Drawing Near to God, Not Just for Sin

The overall idea of sacrifices were that they were intended for drawing near to God. God wanted to dwell among his people, but because he is utterly holy, great effort had to be made to approach him in purity. Some sacrifices were for just that purpose, to sanctify an area to be acceptable in God’s sight.

The need for purification wasn’t necessarily due to any sin, but to ceremonial uncleanness that had to be removed. Sin needed to be atoned for as well, and the blood of a sacrifice was required, as well as repentance on the part of the worshipper.

A common misconception is that all sacrifices were for sin. Because sin and ceremonial uncleanness were intolerable to a holy God, they had to be removed so that his people could draw near him.2

One way we can see the picture of drawing near to God is in one of the most common Hebrew words for an offering, which was korban, derived from the verb karav, meaning “to come near.” This type of offering could be of many types, but it was to be without defect — the finest fruit, or grain, or animals. The people had the privilege of drawing close to a magnificent, glorious God, and nothing but the best would be appropriate to give him.

Another picture of how sacrifices were used to celebrate a relationship with God is in the fellowship or peace, shelem, offerings. These were different in that part of the sacrifice was offered up to God, but then the worshipper and his family and the priests ate some of it as well. The picture here was that God was inviting the worshipper to dine at his table, which was understood to be the very essence of having a peaceful relationship (shalom).

When covenants were made, an animal was sacrificed and all parties ate from it, showing the bond of peace between them and with God. This is the reason that after the covenant on Mt. Sinai, the seventy elders of Israel went up and ate at God’s table (Ex. 24:9-14). It is also the reason that the Passover meal, a fellowship offering, was often used as a celebration of recommitment to Israel’s covenant, and why Jesus chose the Passover at the Last Supper to speak of a “new covenant.”3

Interestingly, the way God partook of a worshipper’s sacrifice was to “smell its pleasing aroma.” It was as if the fire converted the earthly material into smoke, which somehow ascended to God.

It might seem too anthropomorphic to imagine that God has a nose that sniffs from the sky, but to ancient people, it made as much sense as believing that God can “see” us without physical eyes and “hear” our prayers without actual ears. The Hebrew word for “to smell,” rayach, can also have the sense of “delight in” or “enjoy.” When someone gives a wonderful, precious gift to God, he savors it as a delightful aroma.4

I am amply supplied, having received from Epaphroditus what you have sent, a fragrant aroma, an acceptable sacrifice, well-pleasing to God. (Phil. 4:18)

Walk in love, just as Christ also loved you and gave himself up for us, an offering and a sacrifice to God as a fragrant aroma. (Ephesians 5:2)

A Costly Sacrifice

An important part of the sacrifice was its costliness to the worshipper. Before money had been invented, animals and crops were the “currency” of the world, and each animal would have been very expensive. Offerings that could be obtained with little expense or effort, like fish or game caught from the wild, were not used as sacrifices. Instead, animals that a person raised himself or that were purchased were required.

As King David said, “I will not sacrifice to the LORD my God burnt offerings that cost me nothing” (2 Sam. 24:24). Jesus also pointed this out when he said the widow’s mite was worth far more to God than the larger offerings of the wealthy donor, because her gift was a real sacrifice — all that she had to live on (Mark 12:43).

To ancient people, it was very meaningful to feel that they had taken something precious of theirs and given it to God, and that he had accepted it. Or that they had sat at God’s table and eaten a meal in his presence. They felt that they had come close to God, and that he would respond to the needs they brought to him.

Today we often approach God with prayer and singing, but an ancient person likely would feel this was a little less real — like saying that you loved someone, rather than showing your love for them. Certainly at some points the system was abused, but for thousands of years, people expressed their love for God by taking the very best things they had and offering them up to him.5

The Language of Sacrifice

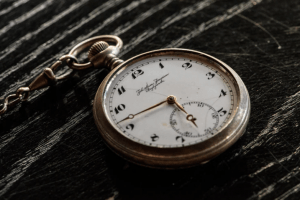

Even though we do not give God sacrifices now, the idea of love being expressed through sacrifice is still universally understood. Many remember the classic short story, The Gift of the Magi, by O. Henry.6 A young couple was nearly penniless, but had two prized possessions: the husband’s pocket watch that had been his father’s and grandfather’s, and the wife’s long, beautiful hair.

At Christmas each one wanted to give the other a gift, so the woman secretly cut off her hair and sold it to a wig maker, and bought her husband a gold chain for the watch. The same day, the man secretly sold his watch to buy an expensive set of combs for her hair. The beauty of the story is in the fact that each was willing to sacrifice their most prized possession for the other. We all can instinctively feel the depth of the love they had for each other.

At Christmas each one wanted to give the other a gift, so the woman secretly cut off her hair and sold it to a wig maker, and bought her husband a gold chain for the watch. The same day, the man secretly sold his watch to buy an expensive set of combs for her hair. The beauty of the story is in the fact that each was willing to sacrifice their most prized possession for the other. We all can instinctively feel the depth of the love they had for each other.

This is a truth that we all know in our hearts: that people will do nothing that works to their own detriment for someone else, except if they truly love them. This is the power of the message of the Gospel — that Jesus suffered and died for us, without us doing anything to deserve it. As Paul said,

Very rarely will anyone die for a righteous man, though for a good man someone might possibly dare to die. But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us. (Romans 5:7-8)

For those of us who believe that Jesus really is God incarnate, this is something we can cling to during times of suffering, when it seems that God might not really care about us. Knowing that God was willing to suffer for us decides the matter once and for all.

God loves us deeply and his great love for us can never be shaken, because he was willing to die for us at our very worst. It is interesting that when humans desired to come near to God, they sacrificed their very finest things to show him their love, and when God desired to draw near to humans, he sacrificed his precious Son!

This language of sacrifice carries across the widest gaps of culture. We learned this during En-Gedi’s trip to install water purification units in Africa some years ago that was led by Bruce Okkema.7 The last unit to be put in was among the Maasai tribe in Kenya. While the other installations went fairly smoothly, this one was fraught with problems, with the expensive pumps repeatedly burning out and the pipeline buckling from the heat of the sun.

The Maasai people watched Bruce work hard through his own weariness and discouragement, cancel his vacation and delay his flight home to finally get it running. When he finally succeeded (with much prayer), what really impressed the Maasai was not the gift of the water unit, which was a tremendous blessing to them. Rather, they told Bruce over and over that they knew he truly loved them when they saw him sacrificing so much of himself to get the job done.

His actions were speaking a universal language. The Maasai had been told about a Jesus who loved them and who died on the cross for them thousands of years ago, but here he was again standing right in front of them, in the person of one of his followers sacrificing himself for them!

As Jesus’ disciples, we are supposed to imitate our rabbi, and we are supposed to raise up other disciples to be like him.8 Christ’s example of being a “living sacrifice” is a model for our way of life, and it is also the most effective way to communicate his love to the world.

~~~~

1 Animals were generally not slaughtered without some kind of sacrifice ceremony. In Deuteronomy 12:15-16, God gave a specific instruction that they were allowed to eat meat that wasn’t sacrificed at the Temple as long as they poured out the blood on the ground. This implied that the Israelites didn’t feel they could do so until told otherwise. (They poured out the blood because God owns the “life,” which the blood signifies.) In the New Testament, the eating of meat sacrificed to idols was also a problem because Gentiles always sacrificed animals to pagan gods before eating them, so all meat for sale was associated with idol worship (1 Cor. 10).

2 Baruch Levine, JPS Torah Commentary on Leviticus, Jewish Publication Society, New York, 1989, p. 216. See also the chapter on korban in Buried Treasure: Secrets from Living from the Lord’s Language by Rabbi Daniel Lapin, (Multinomah, Oregon, 2001) pp. 29-33. And, see The Five Books of Moses by Everett Fox, (Schocken, New York, 1983) pp. 506-508.

3 For more on this, see the article “Eating at the Lord’s Table.”

4 Many Hebrew verbs have broad definitions that include both a sensory input and its outcome — “to hear” also means “to obey,” “to see” can mean “to provide for” and “to remember” can mean “to help.” The idea of smelling a sweet fragrance as “delighting” follows that pattern. See Listening to the Language of the Bible (En-Gedi, 2004) for more.

5 Christians point out that Jesus was the final sacrifice for all sin, but many wonder why the Jewish people stopped sacrificing. The reason was because of the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70, after which there was no acceptable place to sacrifice. Even before the destruction of the Temple, practices were changing to focus on the local synagogue, since only people living in Jerusalem could take part regularly in Temple sacrifices. Modern churches descended from the synagogue, which focused on prayer and study of the Scripture rather than on sacrifice.

6 See “The Gift of the Magi” for the original story by O. Henry, 1905, (public domain).

7 A similar circumstance occurred during of the beginning of En-Gedi’s ministry. Read more in the article “Faith in Doubtful Times: Learning from the Fall Festival.”

8 See the article “Raise Up Many Disciples!” and the book New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus: Insights from His Jewish Context, by David Bivin, (En-Gedi, 2005) pp. 9-21.

Photos: Illustrators of the 1890 Holman Bible [Public domain], Patrick Schneider on Unsplash, Kjartan Einarsson on Unsplash