by Lois Tverberg

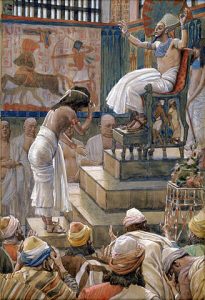

The magicians said to Pharaoh, “This is the finger of God.” But Pharaoh’s heart was hard and he would not listen, just as the LORD had said. – Exodus 8:19

Many of us struggle with the fact that God said that he would harden Pharaoh’s heart, so that God could bring all ten plagues on Egypt before he finally would free the Israelites. It seems like Pharaoh might be innocent pawn which God callously manipulates.

Many of us struggle with the fact that God said that he would harden Pharaoh’s heart, so that God could bring all ten plagues on Egypt before he finally would free the Israelites. It seems like Pharaoh might be innocent pawn which God callously manipulates.

It helps to examine the story more closely. The idea of “hardening the heart” is mentioned twenty times in the Exodus story. The text says ten times that Pharaoh hardened his own heart, and ten times that God hardened it. The first time that God hardened Pharaoh’s heart was in the sixth plague, after Pharaoh had already had five chances to change his mind. With each plague that Pharaoh ignored, it showed that he cruelly cared nothing of the misery of his subjects.

After the third plague, Pharaoh’s magicians declared that the plague of gnats were the “finger of God” – meaning that they were up against something mightier than anything they’d ever known. But in spite of the fact that it was irrational to think that he could defeat this God, Pharaoh refused to yield. At this point, it seems to have become a test of wills between Pharaoh, who considered himself a god, and the real God. Because Pharaoh was understood to be a god himself, his will was absolutely supreme. All decisions of his were uncontested because he held all authority. The fact that God was in control over his power of decision showed that God was ultimately supreme even over him.

We can learn a valuable lesson from this too. When we fall into sin, God is generous with his offers to repent, but at a certain point, our hearts become hardened because of our own desires. As the rabbis used to say, “When sin starts out, it is weak like a spider’s web, but then it becomes as strong as an iron chain.” We should examine ourselves and repent before sin has hardened our wills to the point where we can no longer turn back.

Photocred: Captmondo

They meant that this was the sign of a power far, far greater than they could conjure up. Often God’s power or intervention is described metaphorically by using words like God’s “arm” or God’s “hand.” God’s “finger” also refers to his power or intervention. God is so mighty that all he had to use was his littlest finger to defeat the powers of the magicians in Egypt!

They meant that this was the sign of a power far, far greater than they could conjure up. Often God’s power or intervention is described metaphorically by using words like God’s “arm” or God’s “hand.” God’s “finger” also refers to his power or intervention. God is so mighty that all he had to use was his littlest finger to defeat the powers of the magicians in Egypt! God told Aaron to throw down his staff so that it changed into a snake, fully knowing that the Pharaoh’s magicians could do the same thing. They must have smirked when they saw it, recognizing it from their bag of standard warm-up stunts and laughing to themselves at how easy it would be to replicate. It’s like God was lobbing a slow pitch over the plate for an easy swing – something to draw the attention of the spiritual powers that there was a new “god” in town who

God told Aaron to throw down his staff so that it changed into a snake, fully knowing that the Pharaoh’s magicians could do the same thing. They must have smirked when they saw it, recognizing it from their bag of standard warm-up stunts and laughing to themselves at how easy it would be to replicate. It’s like God was lobbing a slow pitch over the plate for an easy swing – something to draw the attention of the spiritual powers that there was a new “god” in town who When God spoke to Moses in the burning bush and Moses asked his name, God revealed many things about his nature through what he said. His answer likely was not what Moses expected, because God is so utterly unlike the gods that Moses had encountered. Other gods had names that were nouns, like “Molech” (actually Melech, meaning “King”) or “Baal,” meaning “Master,” or perhaps descriptive names like “Lucifer” meaning, “Light Bearer,” or “Baal Zebul” meaning “Exalted Lord.”

When God spoke to Moses in the burning bush and Moses asked his name, God revealed many things about his nature through what he said. His answer likely was not what Moses expected, because God is so utterly unlike the gods that Moses had encountered. Other gods had names that were nouns, like “Molech” (actually Melech, meaning “King”) or “Baal,” meaning “Master,” or perhaps descriptive names like “Lucifer” meaning, “Light Bearer,” or “Baal Zebul” meaning “Exalted Lord.” In the first few chapters of Exodus, women play a major role. Pharaoh tells the midwives Shiprah and Puah to kill the newborn boys but let the girls live. His assumption was that while men posed a threat, women would be easily assimilated into Egyptian culture and exploited as domestic and sexual slaves. We also see hints of this in Abraham’s time, when he tells Sarah that the Egyptians would kill him and take her. (Genesis 12:12)

In the first few chapters of Exodus, women play a major role. Pharaoh tells the midwives Shiprah and Puah to kill the newborn boys but let the girls live. His assumption was that while men posed a threat, women would be easily assimilated into Egyptian culture and exploited as domestic and sexual slaves. We also see hints of this in Abraham’s time, when he tells Sarah that the Egyptians would kill him and take her. (Genesis 12:12)

The rabbis pointed out that this pattern of the punishment fitting the crime is a recurring theme throughout the Scriptures. Because Jacob deceived Isaac in his blindness into giving him the birthright, Jacob is fooled into marrying Leah when he is “blind” – when she is brought to him veiled, and in the night he doesn’t see his new wife. Or, because Pharaoh killed the Israelite boys by drowning them in the river, God defeated his army by drowning them too. Haman was hanged on the gallows that he prepared for Mordechai. The rabbis called this pattern “measure for measure” – midah keneged midah.

The rabbis pointed out that this pattern of the punishment fitting the crime is a recurring theme throughout the Scriptures. Because Jacob deceived Isaac in his blindness into giving him the birthright, Jacob is fooled into marrying Leah when he is “blind” – when she is brought to him veiled, and in the night he doesn’t see his new wife. Or, because Pharaoh killed the Israelite boys by drowning them in the river, God defeated his army by drowning them too. Haman was hanged on the gallows that he prepared for Mordechai. The rabbis called this pattern “measure for measure” – midah keneged midah.

An interesting thing to note was that it seems that even though Joseph had great power in Egypt, he was still a slave even then and not free to leave. In the passage above, when Joseph wanted to travel to Canaan to bury his father, he had to ask permission. Scholars believe that the officials, chariots and horsemen who went with him were there partly to honor Jacob, but also to guard Joseph to make sure that he returned to Egypt.

An interesting thing to note was that it seems that even though Joseph had great power in Egypt, he was still a slave even then and not free to leave. In the passage above, when Joseph wanted to travel to Canaan to bury his father, he had to ask permission. Scholars believe that the officials, chariots and horsemen who went with him were there partly to honor Jacob, but also to guard Joseph to make sure that he returned to Egypt.