by Lois Tverberg

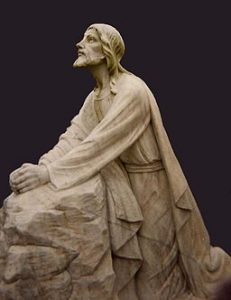

When Jesus was asked the question, “What must I do to inherit eternal life,” the conversation leads to an answer that most Christians would find unacceptable, or at least confusing. It sounds as if by obeying the commandments, or even by loving God and our neighbor, we can somehow earn our own salvation!

We read this conversation in Luke 10:

On one occasion an expert in the law stood up to test Jesus. “Teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?” “What is written in the Law?” he replied. “How do you read it?” He answered: “`Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’; and, `Love your neighbor as yourself.'” “You have answered correctly,” Jesus replied. “Do this and you will live.” Luke 10:25-28

One explanation for Jesus’ response is that because the law expert is testing Jesus out of hostility, Jesus is deliberately affirming his “wrong” answer, so that later, when he realizes his inability to keep these commands perfectly, he will see that he must lean on God’s grace and just believe.

Most likely this is not what was going on. If this is true, it means that Jesus was playing a game with the lawyer, and that his words must be read knowing that no one ever could actually do what he just said to do. While this has satisfied some Christians, having additional information from Jesus’ first century Jewish context can lead to a better reading of this text that explains why Jesus accepted the answer without hidden qualifications.

We should start with the assumption that many times when other rabbis “tested” Jesus, it was not done with hostile intentions. The rabbinic style of public discussion from Jesus’ time even up to the present has been to pose a difficult question with the expectation of debate. A story is even told of a rabbi who greatly mourns the passing of his strongest adversary, because he had lost his best way to sharpen his intellect.1

We tend to assume that every conversation between Jesus and religious thinkers was antagonistic, and hear their questions as legalistic or manipulative. But several questions, like whether divorce was permissible, or what was the “greatest commandment,” were actually important discussions already permeating the rabbinic community of Jesus’ time.2

Love the Lord Your God

The key to understanding Jesus’ affirmative response is to look at the context of how the lawyer’s response was understood in that time. The first line of his answer says, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength and mind,” and comes from Deuteronomy 6:5. We hear “love” as inward affection, and it does mean that. But in Hebrew, the verb “love” can also refer to the outward display of committedness to another. It is to “act lovingly toward” or “to honor and be loyal to.” It was even used in covenants between kings after a war, when one would promise to “love” the other, meaning to show uncompromising loyalty to the other.3

Why is this important? Because then the statement “You shall love the Lord…” then becomes a statement of life commitment to God, and faithfulness to a relationship with him. This is very close to the Christian understanding that we need to have a personal relationship with God for salvation.

Interestingly, the rabbinic term for this idea — to commit yourself to a personal relationship with God, was to “receive the kingdom of Heaven,” very close to what Jesus referred to in his preaching. Why? The word “kingdom” refers to God’s reign or authority, and “Heaven” is a respectful euphemism for God. When we receive the reign of God, what we are actually doing is enthroning him as our king, committing our lives to be under his reign.

This yields a clue as to why Jesus spent so much of his ministry proclaiming the “kingdom of Heaven,” in the sense that he had come to open the way for all people to have a relationship with God through atonement by his blood, and that relationship could be described as “entering under God’s reign.”4

Another important thing about the lawyer’s response was that he was quoting from the Shema, the “pledge of allegiance” that Jews said as a statement of commitment to their relationship with God. The first line is “Hear, O Israel, the Lord is your God, the Lord alone.” According to the Jewish Publication Society, the emphasis is not actually on proclaiming that “God is one,” a creed of monotheism (as is often said), but on the demand of utter loyalty between God and his people — that he alone is their God.5

Obedience Follows Relationship

It may be surprising to some that rabbinic thought of Jesus’ time embraced the idea that salvation comes by faith rather than by works, and they even saw that expressed in the Shema. They understood that the relationship with God must always come first, and only after we have that do we obey God’s commandments.

In the Mishnah6 there is a sermon based on the how the Shema is recited. A person always begins with Deut. 6:4-9, which begins with “Hear O Israel, the Lord is Your God, the Lord alone.” Next they recite Deut. 11:13-21, which begins with the words, “So if you faithfully obey the commands I am giving you today…” The rabbi said,

“Why do we always talk about God being our Lord before we say the part about obeying the commandments? Because we must first receive the kingdom of Heaven (meaning “enthrone God as our king,” or establish our relationship with him) and only then take on the yoke of the commandments.”7

We do not earn our relationship, we receive it as a gift from him, and the laws are not for earning God’s favor or getting into heaven, but for learning how to live to please him. One creative rabbi imagined that King David may have been thinking that when he wrote Psalm 141:1:

King David said, “Some trust in their fair and upright deeds, and some in the works of their fathers, but I trust in you. Although I have no good works, yet because I call upon you, you answer me.”8

Love your Neighbor as Yourself

The other commandment that the lawyer mentioned in Luke 10, “love your neighbor as yourself,” also has special significance. It is a quote from Leviticus 19:18, and it was singled out in ancient Jewish culture before we hear it from Jesus. It has a rare word, ve’ahavta, “and you shall love,” in common with that of words of the Shema that shows total commitment to God, “And you shall love the Lord your God…”

Even before Jesus’ time, those two verses were thought to be linked, in a poetic way, so that the way you expressed your total love and commitment to God, who you can’t see, was by showing love to your neighbor, who you can see. This is certainly a central teaching of Jesus too, and the overwhelming importance of this command is echoed in the rest of the New Testament. Peter says “above all, love one another” (1 Peter 4:8), and in the letters of John, that “this was the teaching you have heard from the very beginning – to love one another” (1 John 3:11).

It appears that this idea may have already been circulating in Jewish culture before his time, and the lawyer was repeating it to Jesus. If Jesus also had the first century understanding that loving your neighbor was the clearest expression of your commitment to God, he would have accepted the lawyer’s words as a way of describing how to live out your relationship with God in obedience and authenticity, by showing God’s love to those around you. Thus, the lawyer gave a very good answer, using first century Jewish terminology to say that we need to commit ourselves to the Lord and live our faith out wholeheartedly. And Jesus responds, “Yes, do this!”

The questioner then goes on to ask, “who is my neighbor,” which also was a legitimate question that was debated at the time, and Jesus gives brilliant insight to this too.9

The Challenge of A Different Understanding

Although this may be a challenge to our traditional Christian view, it suggests that there was some brilliant thinking going on before Jesus’ time, as God was preparing his people for the coming of his Son.

Certainly if Jesus was going to raise up a congregation of many thousand followers out of this Jewish nation (Acts 21:20), God needed to be preparing their hearts for their Messiah. Studying their thinking allows us to see Jesus’ answer as straightforward and clear. He affirms that we need to have a personal relationship with God, and show our commitment to him by loving others in the world around us.

~~~~

This essay is based, in part, on a talk given by Dr. Randall Buth at Mars Hill Bible Church on October 17, 2003.

~~~~

1 Page xiii, Jesus the Jewish Theologian, by Brad Young. Hendrickson, 1995

2 See the article, “Divorce and Remarriage in Historical Perspective” by Steve Notley at www.jerusalemperspective.com.

3 JPS Torah Commentary on Deuteronomy, by Jeffrey Tigay. Jewish Publication Society, 1996, p 77.

4 See the En-Gedi Bible commentary article, “What is the Kingdom of Heaven?“

5 Excursus 10: The Shema in the JPS Torah Commentary on Deuteronomy, p 438-440.

6 The Mishnah is a book of legal rulings and commentary on the Torah written down about 200 AD that is record of sayings that go back to before the time of Jesus.

7 Berachot 2.2, Mishnah.

8 Midrash Psalms 141 (ed. Buber, pp. 530-531).

9 See the En-Gedi Director’s article, “Loving your Neighbor, Who is Like You.“

Photos: Museum of Málaga; Chris Gallimore on Unsplash; Jon Tyson on Unsplash

Interestingly, the Hebrew word besorah, which we translate to “good news,” has exactly that connotation. It is news of national importance: a victory in war, or the rise of a powerful new king. The word was used in relation to the end of the exile (Isaiah 52:7) and the coming of the messianic King (Isaiah 60:1). Often it is news that means enormous life change for the hearer.

Interestingly, the Hebrew word besorah, which we translate to “good news,” has exactly that connotation. It is news of national importance: a victory in war, or the rise of a powerful new king. The word was used in relation to the end of the exile (Isaiah 52:7) and the coming of the messianic King (Isaiah 60:1). Often it is news that means enormous life change for the hearer.