by Lois Tverberg

As part of an insatiable curiosity to understand the Bible’s message in the cultural “language” that it was originally given, I’ve been looking at original cultural message behind our celebration of Communion. Why? Because the ideas behind this practice are found from Genesis to Revelation, and can give us a deeper appreciation of our celebration of the Lord’s Supper.

As part of an insatiable curiosity to understand the Bible’s message in the cultural “language” that it was originally given, I’ve been looking at original cultural message behind our celebration of Communion. Why? Because the ideas behind this practice are found from Genesis to Revelation, and can give us a deeper appreciation of our celebration of the Lord’s Supper.

Eastern cultures throughout Asia and Africa, from the distant past up to the present, have understood that sharing a meal together was a sign of true fellowship. For thousands of years, groups have shared a ceremonial meal together as a symbol of peace and mutual acceptance after making a covenant.

Covenants, in the Eastern mind, are not just business agreements, they are the making of a new relationship between two parties. Often they involve reconciliation after a grievance has been committed. After making a covenant to not take vengeance on each other, the parties sit down to a ceremonial meal. As they eat together, they celebrate their reconciliation with each other, and after that meal, neither party may bring up the grievance ever again.

A fascinating example of this is the account of the sulha, the Arabic word for “table,” or reconciliation meal, between Ilan Zamir, an Israeli Christian, and an Arab family. Zamir had killed the family’s deaf 13 year-old son in a car accident and wanted to seek forgiveness from the family.

He was warned against it, because the cultural traditions would have allowed the family to kill him as vengeance for their son’s death. But an Arab pastor helped him arrange a sulha, a covenant of reconciliation. The ceremony involved Zamir apologizing and offering gifts, the family refusing the gifts, and finally, their sitting down together for a ceremonial meal.

When the father took the first drink of the coffee at the meal, it was a demonstration of his forgiveness. The family then said to him, “Know, O my brother, that you are in place of this son who has died. You have a family and a home somewhere else, but know that here is your second home.” What a picture of reconciliation! (The full story can be found at this link.)

The Covenantal Meal In the Old Testament

We see this ancient tradition in many covenantal ceremonies in the Old Testament. Remember the story of Jacob in which he flees from his father-in-law, Laban, with his wives. Laban pursues him, and in their meeting they enact a covenant between each other that that neither will harm the other as they part ways. After they made the covenant, it says:

Then Jacob offered a sacrifice on the mountain, and called his kinsmen to the meal; and they ate the meal and spent the night on the mountain. Early in the morning Laban arose, and kissed his sons and his daughters and blessed them. Then Laban departed and returned to his place. (Gen. 31:54 – 55)

We also see the meal as part of one of the most important covenants in the Old Testament: the covenant between God and the people of Israel on Mt. Sinai. After enacting this covenant on Mt. Sinai, there is a scene that we can hardly appreciate:

We also see the meal as part of one of the most important covenants in the Old Testament: the covenant between God and the people of Israel on Mt. Sinai. After enacting this covenant on Mt. Sinai, there is a scene that we can hardly appreciate:

Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and the seventy elders of Israel went up and saw the God of Israel. Under his feet was something like a pavement made of sapphire, clear as the sky itself. But God did not raise his hand against these leaders of the Israelites; they saw God, and they ate and drank. (Ex. 24:9-11)

To a Middle Easterner, the implications of this scene would have been profound. God had made a covenant of peace with this nation, and before anything had been done to break it, they had perfect fellowship with God — they could eat and drink in his presence. Because of the covenantal bond made through the blood of the sacrifices, God had accepted them into his presence.

Not only could they be there, but they even could eat a meal, demonstrating their peaceful relationship with him. This was the beginning of God’s answer to the break in fellowship that occurred in the garden of Eden, when humanity was cast out of God’s presence because of sin.

Throughout the Old Testament, this ceremony of eating and drinking in God’s presence is reenacted through the fellowship offering, literally a “shalom” offering. A family would bring an animal to sacrifice to the tabernacle or temple, and the meat would be eaten by the family and the priest, with the best portions burned as an offering to the Lord.

They saw this as true covenantal communion with God — that they could sit down at a meal with him. It was as if he was truly present at the table with them as they ate. In Deuteronomy 14:22-26, God even tells them to save up a tenth of their money each year and bring it to the temple to have a great fellowship meal with him. They could buy anything they wanted, but they had to invite him to the party!

You may spend the money for whatever your heart desires: for oxen, or sheep, or wine, or strong drink, or whatever your heart desires; and there you shall eat in the presence of the LORD your God and rejoice, you and your household. (Deut 14:26)

We also see this fellowship meal in the great celebrations that occur at important redemptive events in the history of Israel. At the exodus from Egypt they celebrated the Passover, and they still eat this meal to celebrate his faithfulness to them. They celebrated either Passover or a great fellowship offering after they entered the promised land (Josh. 5:10), when they renewed the covenant on Mt. Ebal (Josh. 8:31), when Solomon built the temple (1 Kings 8:33), and later when Hezekiah rededicated it (2 Chron 30:21). The meal was a way to renew their covenant with God and rededicate themselves to fulfilling their part of the covenant.

The Meal in the New Testament

This picture of eating a meal together as a sign of reconciliation and peace also runs throughout the New Testament. In Jesus’ parable about the prodigal son, when the son comes home, his father arranges a feast to celebrate that he is now part of the family again. The meal is a celebration of the renewed harmonious relationship between the son and his family.

After Jesus’ resurrection, we read the odd story of Jesus cooking fish and serving breakfast to the disciples (John 21:9-19). The topic of conversation was a break in their relationship. Jesus says to Peter, “Do you love me?” three times, reminding him of his earlier denials at Jesus’ trial, and then Jesus reinstates him as his disciple. The meal is a demonstration of the reconciliation going on between Jesus and Peter.

We even hear this idea of a meal of reconciliation in the familiar words of Revelation 3:20:

Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if anyone hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and will dine with him, and he with Me.

Now we know why it says that Jesus would come in and dine with us: to show us his acceptance of us, and to celebrate the relationship that we have together! It also explains why the predominant picture of heaven is that of a wedding feast, the celebration of the covenantal union of the Lamb and his people. There, we will always have this unbroken fellowship with him.

Communion as Covenantal Meal

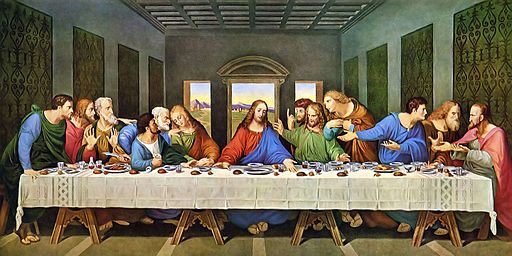

From all of this imagery in scripture, we can have a beautiful new picture of what Jesus intended when, at the Last Supper, he broke the bread, then held up the wine and said, “This is the blood of the new covenant – do this in remembrance of me.” Jesus chooses the fellowship meal that had been used many times to celebrate God’s redemption of his people, the Passover meal.

Now, through the blood of Christ’s sacrifice, he is saying that we can enter into the new covenant of forgiveness and have a new, unbroken relationship with him. Like the Arab father, God puts aside all grievances he has with us, and tells us that we are now members of his family! This ceremony assures us of God’s redemption, that we are acceptable in his sight.

We are also reminded that salvation is not just a future event, not just being saved from our sins when we die. Salvation is our coming into fellowship with God, like the prodigal returning to his family. This supper shows that we can enter into God’s presence and have communion with him even in this life, as the seventy elders did on Mt. Sinai. The beauty of the celebration of the Lord’s Supper lies both in the present enjoyment of fellowship with the Lord, as well as the anticipation of unending fellowship with him at the banquet in heaven.

~~~~

Photos: Eczebulun [CC BY-SA 3.0], Berthold Werner [CC BY-SA 3.0], Da Vinci [Public Domain]