by Lois Tverberg

The LORD said to Moses and Aaron in Egypt, “This month is to be for you the first month, the first month of your year.” Exodus 12:1-2

The very first instruction that God gave the Israelites as they were leaving Egypt was to establish a new calendar that was utterly unlike the Egyptian calendar. This may not seem significant to us, but how we measure time is fundamental for how we look at life. Our calendars define the importance of the day to the entire culture, saying whether we should work, rest or worship, or think about some great event in our past.

The very first instruction that God gave the Israelites as they were leaving Egypt was to establish a new calendar that was utterly unlike the Egyptian calendar. This may not seem significant to us, but how we measure time is fundamental for how we look at life. Our calendars define the importance of the day to the entire culture, saying whether we should work, rest or worship, or think about some great event in our past.

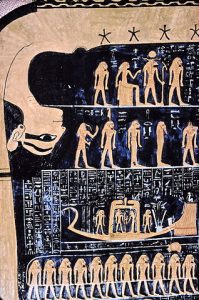

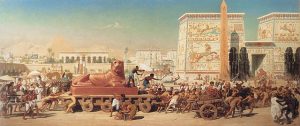

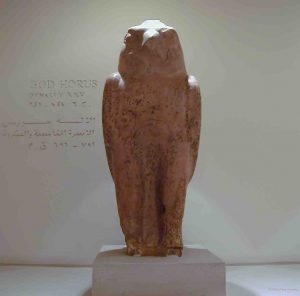

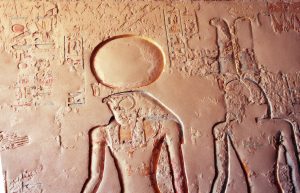

This was especially critical as the Israelites left the powerful nation of Egypt, which had strongly influenced their thinking while they lived there. Egypt had a twelve-month solar calendar that was entirely organized around the veneration of their gods. Their year started in late June when the brightest star in the sky, Sirius, arose, about the time of the flooding of the Nile. They spent five days in feasting and worship beforehand, pleading with their gods for a good flood of the Nile and good harvest for that year. Each of the 36 ten-day weeks of the year was dedicated to a different god.

In contrast, God instructed Israel to mark time by remembering their redemption from Egypt. Their calendar no longer focused on idolatrous gods, but on permanently remembering the true God that loved them so much that he freed them from slavery. Every aspect of their calendar repeated this motif. The other major feast of the year, the feast of booths (Sukkot), also focused on reliving their time in the wilderness after God brought them out of Egypt. Even the seven-day week was founded on remembering how God had granted them rest from slavery:

You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the LORD your God brought you out of there by a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm; therefore the LORD your God commanded you to observe the sabbath day. Deut. 5:15

Also, the law to celebrate the fiftieth year as a Year of Jubilee was also founded on the idea that they set free those who are in debt, just as God set them free.

If one of your countrymen becomes poor among you and sells himself to you, do not make him work as a slave. He is to be treated as a hired worker or a temporary resident among you; he is to work for you until the Year of Jubilee. Then he and his children are to be released. Because the Israelites are my servants, whom I brought out of Egypt, they must not be sold as slaves. Lev. 25:39-41

All of their worship and time focused on remembering how God saved them and took them to be their people. In the same way, we as Christians should continually remind ourselves of our redemption in Christ, the Passover Lamb, by his death for our sins. Every day of our lives should revolve around living out of this truth.

Photo: Hans Bernhard (Schnobby) and Edward Poynter

e LORD said to Moses, “When you go back to Egypt see that you perform before Pharaoh all the wonders which I have put in your power; but I will harden his heart so that he will not let the people go. – Exodus 4:21

e LORD said to Moses, “When you go back to Egypt see that you perform before Pharaoh all the wonders which I have put in your power; but I will harden his heart so that he will not let the people go. – Exodus 4:21 Israelites, but to declare that God was supreme over the many “gods” that Egypt worshipped (Ex.

Israelites, but to declare that God was supreme over the many “gods” that Egypt worshipped (Ex. They meant that this was the sign of a power far, far greater than they could conjure up. Often God’s power or intervention is described metaphorically by using words like God’s “arm” or God’s “hand.” God’s “finger” also refers to his power or intervention. God is so mighty that all he had to use was his littlest finger to defeat the powers of the magicians in Egypt!

They meant that this was the sign of a power far, far greater than they could conjure up. Often God’s power or intervention is described metaphorically by using words like God’s “arm” or God’s “hand.” God’s “finger” also refers to his power or intervention. God is so mighty that all he had to use was his littlest finger to defeat the powers of the magicians in Egypt! God told Aaron to throw down his staff so that it changed into a snake, fully knowing that the Pharaoh’s magicians could do the same thing. They must have smirked when they saw it, recognizing it from their bag of standard warm-up stunts and laughing to themselves at how easy it would be to replicate. It’s like God was lobbing a slow pitch over the plate for an easy swing – something to draw the attention of the spiritual powers that there was a new “god” in town who

God told Aaron to throw down his staff so that it changed into a snake, fully knowing that the Pharaoh’s magicians could do the same thing. They must have smirked when they saw it, recognizing it from their bag of standard warm-up stunts and laughing to themselves at how easy it would be to replicate. It’s like God was lobbing a slow pitch over the plate for an easy swing – something to draw the attention of the spiritual powers that there was a new “god” in town who When God spoke to Moses in the burning bush and Moses asked his name, God revealed many things about his nature through what he said. His answer likely was not what Moses expected, because God is so utterly unlike the gods that Moses had encountered. Other gods had names that were nouns, like “Molech” (actually Melech, meaning “King”) or “Baal,” meaning “Master,” or perhaps descriptive names like “Lucifer” meaning, “Light Bearer,” or “Baal Zebul” meaning “Exalted Lord.”

When God spoke to Moses in the burning bush and Moses asked his name, God revealed many things about his nature through what he said. His answer likely was not what Moses expected, because God is so utterly unlike the gods that Moses had encountered. Other gods had names that were nouns, like “Molech” (actually Melech, meaning “King”) or “Baal,” meaning “Master,” or perhaps descriptive names like “Lucifer” meaning, “Light Bearer,” or “Baal Zebul” meaning “Exalted Lord.” In the first few chapters of Exodus, women play a major role. Pharaoh tells the midwives Shiprah and Puah to kill the newborn boys but let the girls live. His assumption was that while men posed a threat, women would be easily assimilated into Egyptian culture and exploited as domestic and sexual slaves. We also see hints of this in Abraham’s time, when he tells Sarah that the Egyptians would kill him and take her. (Genesis 12:12)

In the first few chapters of Exodus, women play a major role. Pharaoh tells the midwives Shiprah and Puah to kill the newborn boys but let the girls live. His assumption was that while men posed a threat, women would be easily assimilated into Egyptian culture and exploited as domestic and sexual slaves. We also see hints of this in Abraham’s time, when he tells Sarah that the Egyptians would kill him and take her. (Genesis 12:12)

The rabbis pointed out that this pattern of the punishment fitting the crime is a recurring theme throughout the Scriptures. Because Jacob deceived Isaac in his blindness into giving him the birthright, Jacob is fooled into marrying Leah when he is “blind” – when she is brought to him veiled, and in the night he doesn’t see his new wife. Or, because Pharaoh killed the Israelite boys by drowning them in the river, God defeated his army by drowning them too. Haman was hanged on the gallows that he prepared for Mordechai. The rabbis called this pattern “measure for measure” – midah keneged midah.

The rabbis pointed out that this pattern of the punishment fitting the crime is a recurring theme throughout the Scriptures. Because Jacob deceived Isaac in his blindness into giving him the birthright, Jacob is fooled into marrying Leah when he is “blind” – when she is brought to him veiled, and in the night he doesn’t see his new wife. Or, because Pharaoh killed the Israelite boys by drowning them in the river, God defeated his army by drowning them too. Haman was hanged on the gallows that he prepared for Mordechai. The rabbis called this pattern “measure for measure” – midah keneged midah.