by Lois Tverberg

Cursed (Arur) is the man who trusts in mankind and makes flesh his strength, whose heart turns away from the Lord. He will be like a bush (arar) in the desert, and will not see when prosperity comes, but will live in stony wastes in the wilderness, a land of salt without inhabitant. (Jer. 17:5)

But blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord, whose confidence is in Him. For he will be like a tree planted by the water, that extends its roots by a stream. It will not fear when the heat comes, but its leaves will be green, and it will not be anxious in a year of drought, nor cease to yield fruit. (Jer 17:7)

After reading this proverb about the cursed tree and the blessed tree, it is easy to imagine what the blessed tree must look like — thick green leaves; branches covered in large, luscious fruit; abundant growth even when everything is dry all around.

After reading this proverb about the cursed tree and the blessed tree, it is easy to imagine what the blessed tree must look like — thick green leaves; branches covered in large, luscious fruit; abundant growth even when everything is dry all around.

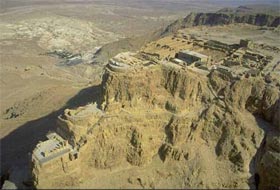

We came to a tree that fit that image perfectly while nearing the end of a trip to Israel a few years back. The tree I’m referring to is in the picture to the left. It was just outside the nature preserve of the En-Gedi springs, a beautiful oasis in the middle of the Judean wilderness, near the barren salt flats that surround the Dead Sea.

The remarkable thing about this beautiful tree is that it is actually the cursed tree that Jeremiah spoke about in this proverb. According to Nogah Hareuveni, an expert on plants of the Bible, in Hebrew the name of this tree is called the Arar, which sounds similar to the word for cursed, arur, and is part of a wordplay which is central to this poem.

Why is it called “cursed”? Because if a thirsty, hot traveler approaches the tree and picks a nice big fruit, he will find a nasty surprise. When opened, the fruit makes a “pssst” sound, and is hollow and filled with webs and dust and a dry pit.

Why is it called “cursed”? Because if a thirsty, hot traveler approaches the tree and picks a nice big fruit, he will find a nasty surprise. When opened, the fruit makes a “pssst” sound, and is hollow and filled with webs and dust and a dry pit.

The Bedouin call this tree the “Cursed Lemon” or “Sodom Apple” because it grows in the salt lands that surround the Dead Sea where Sodom and Gomorrah once were. According to their legends, when God destroyed Sodom, He cursed the fruit of this tree also.

I first heard about this tree from Ray Vander Laan, and I was captivated by the imagery both of the tree itself and what Jeremiah says about it in the poem. From studying Hebrew and being in Israel, I’ve seen even more depth of imagery in this poem. Here are some of my thoughts about it:

I first heard about this tree from Ray Vander Laan, and I was captivated by the imagery both of the tree itself and what Jeremiah says about it in the poem. From studying Hebrew and being in Israel, I’ve seen even more depth of imagery in this poem. Here are some of my thoughts about it:

In Hebrew, the future tense is used in proverbs to indicate an indefinite length of time. So in Hebrew, it sounds like you say, “A stitch in time will save nine.” If, then, you assume that the future tense of the Jeremiah passage is more of the proverbial sense that we have in English, this is what it sounds like:

Cursed is the man who trusts in mankind and makes flesh his strength, whose heart turns away from the Lord. He is like a bush in the desert, which does not see when prosperity comes, but lives in stony wastes in the wilderness, a land of salt without inhabitant. (Jer. 17:5)

(But) blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord, whose confidence is in Him. For he is like a tree planted by the water, that extends its roots by a stream. It doesn’t fear when the heat comes, but its leaves are green, and it is not anxious in a year of drought, and doesn’t cease to yield fruit. (Jer 17:7)

Once I started reading the poem this way, I saw it very differently. I used to think that the cursing was done by God, in order to punish a person for not trusting. Now, I see this as the natural consequences of action, and see it in my own life. When I assume that my strength comes from myself, I am filled with worry all the time. Even when times are good I can’t see the prosperity around me! All my circumstances seem negative, like a barren wasteland; and I feel lonely and weary even when friends and family are nearby.

On the other hand, when I put my trust in God, I can live with relatively little anxiety even in the worst times. One couple I know had a house fire that destroyed all of their possessions while they were away from home. The insurance adjuster couldn’t understand why they were calm and collected, but it was because they saw that God had saved their family and was obviously taking care of them through it. They simply weren’t experiencing the drought the way they would have if they didn’t see God’s hand surrounding them.

On the other hand, when I put my trust in God, I can live with relatively little anxiety even in the worst times. One couple I know had a house fire that destroyed all of their possessions while they were away from home. The insurance adjuster couldn’t understand why they were calm and collected, but it was because they saw that God had saved their family and was obviously taking care of them through it. They simply weren’t experiencing the drought the way they would have if they didn’t see God’s hand surrounding them.

One interesting contrast is that in the literal Hebrew, the cursed person “doesn’t see the coming of good” while the blessed person “doesn’t fear the coming of heat.” At first I thought it was odd that heat is considered a negative, but when my thermometer peaked at 120 degrees while at En-Gedi, I understood.

In Israel, everything is dry and dead in the summertime because of the heat, and the winter is the time of growing crops. Israelis tend to look at summer in the way that Westerners look at winter — a difficult and depressing time that comes every year. They also have a special blessing to praise God every time it rains, which gives life to their land. Think about that next time you complain about a rainy day.

Another image that I got from this poem is that in some sense, the tree actually chooses where it is going to live. Does it choose to live by the river, or does it choose to live in the barren wasteland? Ironically, this Arara tree was within sight distance of both the lush oasis of En-Gedi and the amazingly barren Dead Sea. It seems to be symbolic of my own life which goes back and forth between an excited faith in God, and depressing cynicism about what the future may hold. I seem to choose my location day by day.

Finally, from looking at the cursed tree, what really is wrong with it? Essentially, it can grow tall and get leafy, but the big problem is that the fruit has no juice. In essence, the tree is supposed to absorb life-giving water from the soil and pass it on to others through its fruit, but this is not happening. It is as if the tree has cut itself off from the source of living water by relying on its own strength. It looks fine from the outside, but yields empty fruit.

In some sense, the juice is the maim chaim, “living water,” of the Holy Spirit, which Jesus says will pour out of the one who believes in him (John 7:38). The “juice” comes having a life that is filled with the refreshing presence of the Lord, and without that, our lives are empty and hollow.

The first time I heard it was from a dear friend in Israel when he had found out that his wife had breast cancer. It is never appropriate as an unsympathetic platitude, but from the lips of a person who is suffering, it is a statement of great faith in God — that even in the worst times, we know that a loving God intends it for good.

The first time I heard it was from a dear friend in Israel when he had found out that his wife had breast cancer. It is never appropriate as an unsympathetic platitude, but from the lips of a person who is suffering, it is a statement of great faith in God — that even in the worst times, we know that a loving God intends it for good.