When you pray, say: “Father, hallowed be your name….’” (Luke 11:2)

The Lord’s Prayer is loaded with meaning that we don’t fully appreciate because of cultural differences.1 In particular, the phrase “hallowed be your name” sounds foreign to us. This phrase is very rich in its original context and has an important lesson for our calling as Christians.

The Lord’s Prayer is loaded with meaning that we don’t fully appreciate because of cultural differences.1 In particular, the phrase “hallowed be your name” sounds foreign to us. This phrase is very rich in its original context and has an important lesson for our calling as Christians.

God’s Name as His Reputation

In ancient thinking, a person’s name was connected with his identity, authority and reputation. You might not think that God’s reputation would be an issue, but the idea of his reputation growing greater and greater throughout the world is a central theme of the biblical story.

At first, God taught only one nation, the Jews, how to live and he told them to be a “kingdom of priests” and a “light to the nations” so that the world may know about the true God of Israel (Ex. 19:6).2 Then, in the coming of Christ, God made his identity more clear, and sent his people to “make disciples of all nations” (Mt 28:19).

The overall idea is that God’s reputation would expand over the earth as people come to know who he is. This is the means by which salvation is being brought to the world as people hear good things about God, and accept Christ as their Savior. We can see that God’s reputation, or God’s “name” is of critical importance for his plan of salvation.

In the Lord’s prayer, the phrases “hallowed be your name,” “your kingdom come,” and “your will be done on earth” are related to each other in meaning. All of them are expressing the desire that God’s reputation grow on earth, that people accept God’s reign and desire to do his will.

This is probably the main intent of Jesus’ use of “hallowed be your name,” but an excellent lesson for how it is accomplished comes from the Jewish understanding of the idea of “hallowing (sanctifying) the name,” Kiddush HaShem. The opposite is Hillul HaShem — to profane the name.3 These two phrases are rich with significance in Jewish tradition and are still used today.

Why is Keeping God’s Name Holy So Important?

The rabbis of Jesus’ time closely studied the scriptures and made an interesting observation. Out of all of the ten commandments, only one carried with it a grave threat of punishment. Surprisingly it is not the prohibition against theft or murder, but rather against taking the name of the Lord in vain! The scriptures say “You shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain, for the LORD will not leave him unpunished who takes His name in vain” (Ex. 20:7 NASB).

Does it seem strange that this commandment, which we interpret as a prohibition against swearing, is the only one that God promises to punish? Aren’t other sins equally or more serious?

The rabbis believed that this commandment may also have a much greater meaning.4 They pointed out that the command literally says, “You shall not lift up the name (reputation) of the Lord for an ’empty thing,'” and they interpreted that to mean, to do something evil in the name of God which would give God a bad reputation.

In Lev. 19:12, this is called “profaning the name of God”, and is referred to as Hillul HaShem in Hebrew. It is to do something evil and associate the name of God with it, which is a sin against God himself who suffers from having his reputation defamed.

Profaning the Name of God

Some examples of this clarify why “profaning the name of God” is considered an extremely serious sin. When a terrorist shouts out “Allah Akbar” (God is great) before carrying out acts of murder, the response of the world is to say, “What wicked God do you serve who commands you do such terrible things?”

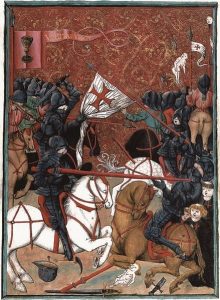

This not only occurs in other religions, but unfortunately in Christianity as well. When televangelists commit fraud, it hardens non-believers to the message of Christ. Or, consider the Crusades, which happened almost a thousand years ago. They are still remembered with hatred because Christians murdered Jews and Muslims in the name of Christ. God’s reputation in the world has been slandered, and evangelism is seriously hindered because of the evil actions of those who bear his name.

This not only occurs in other religions, but unfortunately in Christianity as well. When televangelists commit fraud, it hardens non-believers to the message of Christ. Or, consider the Crusades, which happened almost a thousand years ago. They are still remembered with hatred because Christians murdered Jews and Muslims in the name of Christ. God’s reputation in the world has been slandered, and evangelism is seriously hindered because of the evil actions of those who bear his name.

Even in the lives of average people, this can happen. How many stories have we heard of people who were treated unfairly by church members, and have never returned to the church? They have said in their hearts, “I don’t want anything to do with you or your God.” When a church-goer is dishonest in business, rude to his neighbors, or regularly uses profanity and dirty jokes, it is a witness against Christ to the world around us. Each of us is easily capable of profaning God’s name, a very serious sin indeed.

To Sanctify the Name

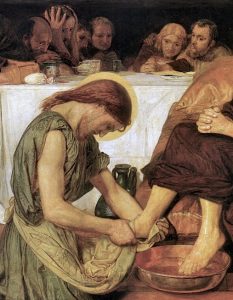

Just as evil actions can damage the reputation of God in the world, good actions can bring honor to God, and this is called “sanctifying God’s name,” Kiddush HaShem. This means to live in such a way as to bring God glory — as when Jesus said, “Let your light shine before men, that they may see your good deeds and praise your Father in heaven” (Matthew 5:16).

The rabbis described it as one of three things: to live a life of integrity, carefully observing the biblical commands; or to do some heroic deed, like risking one’s life to save another; or even to be martyred to honor God. We think of spreading the gospel through information, but they point out that the world is watching our lives too. When we think of sanctifying God’s name, these stories speak volumes:

- Many En-Gedi supporters contributed money toward the installation of some water units for villages in Uganda. When the site preparation team was visiting these sites, they were welcomed enthusiastically by each village with a ceremony of thanks. Our local coordinator, Rev. Titus Baraka, made a point to explain that these water systems were brought in the name of Jesus Christ, who brings living water to the world. He also explained that this water is not only for Anglicans or Protestants, or Catholics or Muslims, but for everyone in the community.

One local water committee member stood up to make the following remark: “I represent the Muslim community here. When I see that you have come here at great expense… when I see the way you do your work… when I see that you want to show love to people you don’t even know, I realize that you serve a greater God than I do. It makes me want to “cross over” to become a Christian.” - Jonathan Miles is a Christian who has a ministry of bringing Palestinian and Iraqi children to Israeli hospitals for heart surgery.5 His work has a powerful impact on the Muslims and Jews who see him and his staff regularly risk their lives, in the name of Christ, to serve others.

One time, while he was waiting to pick up an infant in Gaza, he was verbally assaulted by a Hamas member for several minutes. When the man finally asked him why he was there, he explained that he was trying to locate a certain infant who needed medical care. When the man heard what his mission was, he was like a balloon quickly deflated!

He immediately asked how he could help and took Jonathan all around town searching for the infant. They actually became friends over time! Jonathan said that the man is now even considering becoming a Christian. What a profound change came over this man from Jonathan’s actions to serve God.

Hallowing God’s Name with our Lives

We have all heard of heroic Christians like Corrie Ten Boom or Dietrich Bonhoeffer who by their actions make people ask the question, “Who is this Christ, that you would sacrifice so much to serve him?”

The ultimate example of sanctifying God’s name, however, is Jesus himself. As God incarnate, his death on the cross has proclaimed to all the world that the God of Israel is a merciful, self-sacrificial God. No one who believes that Jesus is God himself can claim that God is cruel or uncaring because Jesus has proven otherwise through his own actions. Because of his great sacrifice, God’s reputation has expanded to the ends of the world.

The ultimate example of sanctifying God’s name, however, is Jesus himself. As God incarnate, his death on the cross has proclaimed to all the world that the God of Israel is a merciful, self-sacrificial God. No one who believes that Jesus is God himself can claim that God is cruel or uncaring because Jesus has proven otherwise through his own actions. Because of his great sacrifice, God’s reputation has expanded to the ends of the world.

As Jesus’ followers, we are commanded to be like him, as a “nation of priests” and a light to the world. We need to be always aware that the world is watching, so that our actions always reflect the holiness and love of the God that we serve.

But you are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people belonging to God, that you may declare the praises of him who called you out of darkness into his wonderful light (1 Peter 2:9).

We are under constant scrutiny whether we are aware of it or not. Let us always try to be a favorable witness to the Holy Name whose image we bear.

~~~~

1 A series of articles on the Lord’s Prayer in its Jewish context by Dr. Brad Young can be found at www.jerusalemperspective.com. (Premium Content subscription required.)

2 See the En-Gedi article “Letting Our Tassels Show” for more about the idea of being a “kingdom of priests.”

3 H. H. Ben-Sasson, Kiddush Ha-Shem and Hillul HaShem, Encyclopedia Judaica CD-ROM, Version 1.0, 1997

4 J. Telushkin, The Book of Jewish Values, p 197. Copyright 2000, Bell Tower. ISBN 0-609-60330-2. (This is an outstanding book on ethics for living. Available at Barnes & Noble or online.)

5 Jonathan Miles’ ministry is called Shevet Achim.

Photos: Yoav Dothan [Public domain]; Jenaer Kodex [Public domain]; Painting “Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet” by Ford Maddox Brown)