by Lois Tverberg

The Spirit of the Sovereign LORD is on me, because the LORD has anointed (“messiah”ed) me to preach good news to the poor. He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty for the captives and release from darkness for the prisoners, to proclaim the year of the LORD’s favor. Isaiah 61:1-2, quoted in Luke 4:18-19

Jesus stood up in in the synagogue at Nazareth and quoted the words of Isaiah 61, and then said, “Today these words are fulfilled in your hearing.” He was applying to himself the role of the “Anointed” one, the Messiah, who was bringing a year of Jubilee, “the year of the LORD’s favor.”

Jesus stood up in in the synagogue at Nazareth and quoted the words of Isaiah 61, and then said, “Today these words are fulfilled in your hearing.” He was applying to himself the role of the “Anointed” one, the Messiah, who was bringing a year of Jubilee, “the year of the LORD’s favor.”

When we hear about a year of Jubilee as a picture of the coming of Christ, we think of it as a joyous year of celebration. We may think about how no one could till their land that year, so it sounds like a wonderful time of ease and rest, like heaven itself. Or we may think of how wonderful it would be to have all our debts forgiven.

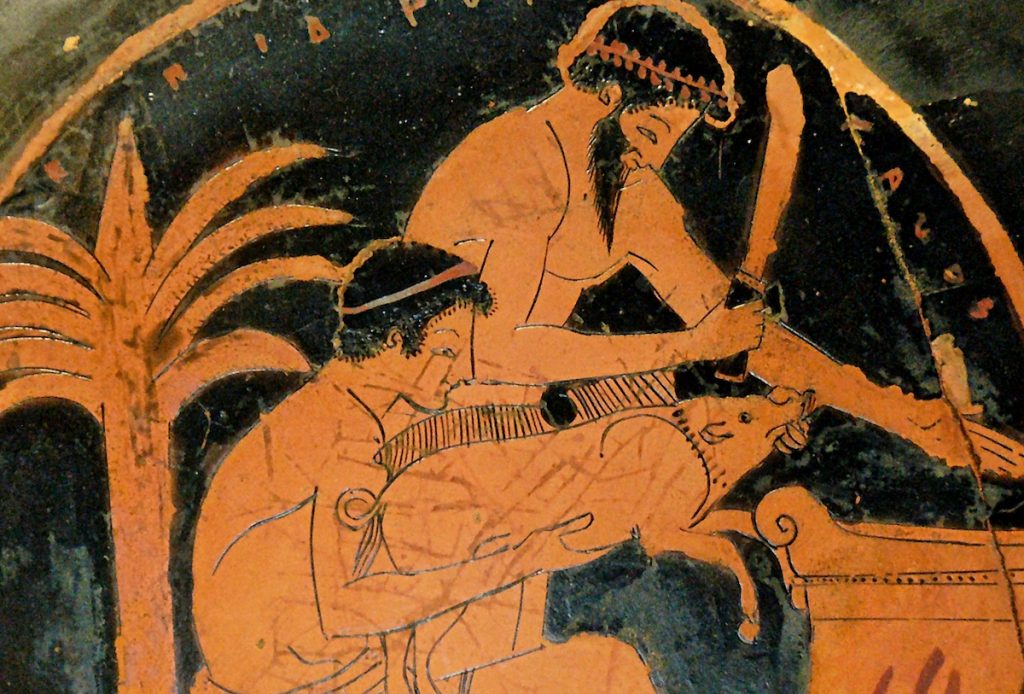

The thing that is puzzling is that it describes the Jubilee as “good news to the poor.” Why wouldn’t the Jubilee be good news to everyone? If we look at the observance of the Jubilee year, it really would only be a delight for the poorest people in the land. For the rich who had bought land, they would have lost their holdings by giving it back to the original owners.

For all, it would have been a time of relative lack – they still had to feed their families, but the fields were not to be planted. That meant that for that one year, the farm-based society had to live on savings, or else glean from what grew up on its own, like the poor people did all the time. The day laborer, who earned barely enough each day to feed his family, would find that year especially difficult because he would not be able to get work on farms.

The only person who would greatly benefit from the Jubilee is the poorest of the poor, who had become so impoverished that he had to borrow (which was only done in desperation), or was forced to sell his land, or even be thrown in debtor’s prison. For him, he experienced the greatest joy at being released from debt that was strangling him.

That can actually teach us about Jesus’ mission, because if we see that debt was a metaphor for sin in the time of Jesus, we see his true mission on earth. It was only the truly poor in spirit who wanted mercy from the Messiah. Most of the society was looking for a Messiah who would come as military King who would judge and destroy their enemies and liberate them. They saw themselves as basically righteous, and their enemies as the sinners of the world. Only those who recognized their own sinfulness would see the great debt they were in, and would want a messiah to come who would come with forgiveness for both them and their enemies. For these, Jesus truly had come with the good news of Jubilee.

Photo: Augustus Binu