by Lois Tverberg

Freedom is the theme of God’s greatest miracles in history. Jews look back on the freeing of Israel from bondage in Egypt as their foundation as a people. They still celebrate this yearly at Passover, when they commemorate the night they were liberated. Christians recall Jesus’ death and resurrection as an act that brought far greater freedom for all people who believe in him, from bondage to sin and death itself.

Freedom is the theme of God’s greatest miracles in history. Jews look back on the freeing of Israel from bondage in Egypt as their foundation as a people. They still celebrate this yearly at Passover, when they commemorate the night they were liberated. Christians recall Jesus’ death and resurrection as an act that brought far greater freedom for all people who believe in him, from bondage to sin and death itself.

In light of these two great acts of liberation from bondage, we may be uncomfortable with the fact that instead of speaking only of freedom, Jesus and Paul often speak about being “slaves” to God or Christ. Jesus says that “You cannot serve two masters, God and money” (Matt 6:24), and Paul says, “You were bought at a price” (1 Cor. 6:19 & 7:23). Paul and other New Testament authors also introduce themselves at the beginning of each book as being “slaves of Christ.”1

It seems paradoxical to speak about slavery and being set free simultaneously, but if we look back and understand God’s first redemption of Israel, we will see how this really is a theme from the beginning of the scriptures to the end. God set his people free from cruel masters to become his own, as their rightful Lord. Both at the first exodus and in Christ’s fulfillment, this picture teaches us much about what our relationship to God really is.

Set Free from Cruel Masters

The common belief of people in the ancient near east was that the world is filled with many spiritual beings that control nature and prosperity. These “gods” were unpredictable and cruel, and used humans as playthings and slaves to serve their own desires.2 Ancient people understood that all people were the slaves of the gods, and each tribe had its own gods that ruled over them, so that to survive, they had to appease the gods through religious ceremonies and magical incantations.

Because of these beliefs, many ancient writings reflect a perpetual sense of hopelessness, anxiety and fear of the spirit world that was hostile to humanity. Interestingly, this pessimistic worldview of polytheism is widespread, from ancient times even up to today.3

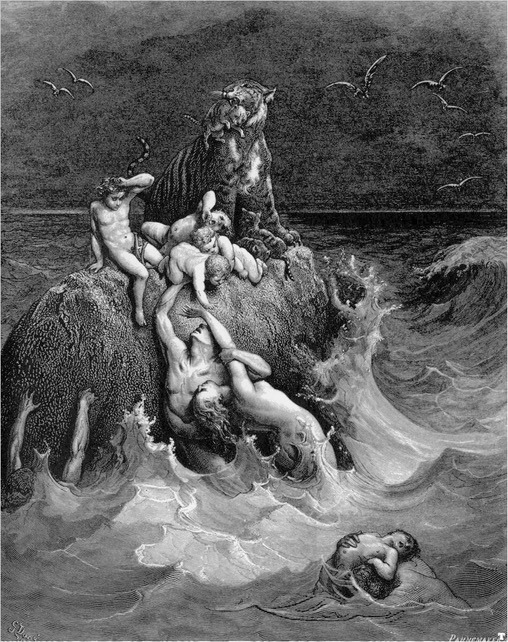

Knowing this helps us read the story of the redemption of Egypt as an ancient person would have understood it. They saw this story as a true spiritual battle between the God of Israel and the gods of the Egyptians. Not only were the Israelites in bondage to physical slavery, they were in bondage to these evil gods, including Pharaoh, who considered himself a god.

Knowing this helps us read the story of the redemption of Egypt as an ancient person would have understood it. They saw this story as a true spiritual battle between the God of Israel and the gods of the Egyptians. Not only were the Israelites in bondage to physical slavery, they were in bondage to these evil gods, including Pharaoh, who considered himself a god.

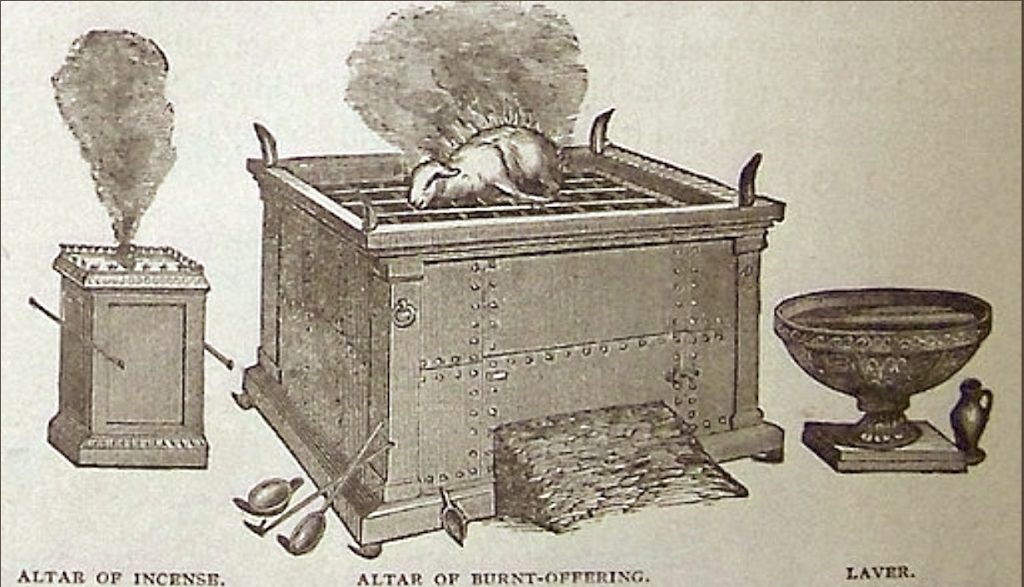

Each plague was directed at a specific god of the Egyptians: Hekt, the frog god; Hapi, the Nile god; Ra, the sun god, etc., and the final plague was against Pharaoh himself (Ex. 12:12). The imagery here is that as God fought and defeated each one, God was winning a battle to take his own people out of the hands of other “gods” so that he would be their God, and they would become his people — his “slaves” as it were (Ex. 6:7, 2 Sam. 7:23).

A key to understanding this is to look at the Hebrew word for “worship,” avad, which has parallels in other languages of the near east. Along with meaning “worship,” it also means “serve” or “work,” and the related noun, eved, means “servant” or “slave.” So, the “worshippers,” avadim, of a god could also be seen as the god’s servants or slaves.

When God challenged Pharaoh, “Let my people go so that they may avad me” (Ex. 8:1), this didn’t just mean so that they could worship him, but that they were to be freed from slavery to the false god Pharaoh, so that they could avad, serve and worship their rightful God.

God later commanded that his people should “worship,” avad, no other gods, which can also be translated to mean

God’s Compassion on Mount Sinai

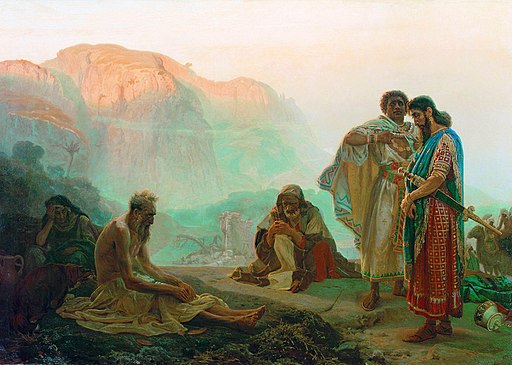

After Israel was freed from bondage, they arrived at Mount Sinai, where God gave him his laws that showed how he wanted them to avad, worship and serve him as his people. We hardly think to compare the laws of the Torah to other law codes of the time, but it is interesting to see how God’s rules show that their new “master” was vastly different from their old masters — he governed with great compassion, and cared about the needs of his people.

After Israel was freed from bondage, they arrived at Mount Sinai, where God gave him his laws that showed how he wanted them to avad, worship and serve him as his people. We hardly think to compare the laws of the Torah to other law codes of the time, but it is interesting to see how God’s rules show that their new “master” was vastly different from their old masters — he governed with great compassion, and cared about the needs of his people.

We modern-day readers hardly appreciate the profound ethical change that the laws of the Torah made relative to other codes of its time, and how fundamental its precepts are to our own laws.5

Other codes had no ethic of equal treatment in regard to rich and poor, so a crime against a person of a high class carried a much greater punishment than one against a low class person. Cheating in a business transaction with a high class person carried the death penalty. In contrast, murder of a lower class person was punishable by a fine based on his social status. In Israel, all were alike under the law, and poor and rich treated equally.

In cases of crime, the Torah was far more humane. In other countries, punishments for even minor crimes were often brutal and mutilating, and often including floggings, amputation and torture. In the Torah, fines were common but physical punishments were rare, and only for severe offenses against the nation or God.

The law that sounds most shocking, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” is actually misunderstood. The expression was actually an idiom that wasn’t taken literally, but actually meant equitable punishment that fits the crime. (An eye for an eye — not a scolding for an eye, or a life for an eye.) It was an ancient expression from laws originally meant to limit punishment for an injury to no more than the injury itself, because without it, the victim’s clan would want greater vengeance, escalating into feuds. Scholars believe that it was not followed literally in Israel, but monetary fines were given for injuries instead.

In other codes, very little protection was given to those who were vulnerable to exploitation. The main goal of other law codes was to protect the assets of the wealthy from the lower class by threatening them with punishment for theft or destruction of property. Israel’s laws were instead very concerned for the protection of the poor, the alien, the widows and orphans.

People were to tithe their money to give to the poor, and let them glean from their crops (Deut. 18:29, Lev. 23:22). They were not to mistreat an alien, but to “love them as themselves” (Lev. 19:34). Much of the code of Israel is specifically written to protect the weakest members of the society, unlike any other nation of the time.6

With these differences in mind, the laws of the Torah show great fairness toward all levels of society, compassion for the vulnerable, and amazing concern for the sanctity of human life. Our own culture has been so transformed by these basic principles that we can hardly imagine the world without them.

The more we see the contrast between God’s ways and the rest of the ancient world, the more we see that the love of Christ in the gospels was fully present in the God who revealed himself on Sinai. In essence, we see the Father and Son as one and the same. The God who Israel was to avad, worship, cared deeply for humanity, and his servants were to mirror his concern as well.

Being God’s Slave to be Free

The most striking difference between God’s ethics compared to other nations was the laws regulating slavery, which teach us a lot about how God viewed his people as his own avadim. In the ancient world, slavery was a given. Knowing that humanity can only change so much, God did not outlaw it, but he gave laws that made it far more humane.

Many of the Torah’s regulations were unheard of in any other culture, and ultimately aimed to undermine the practice altogether. Only six days a week could a master demand a slave to serve him — all slaves had a day of rest every week, and celebrated holy days, too. If a master permanently injured a slave in any way, even causing him to lose a tooth, the slave was given his freedom. Women slaves were to have equal rights as other daughters and wives.

If the slave was a Hebrew who had sold himself because of debt, he had to be freed in six years and given a substantial gift of crops and supplies when he left (Deut. 15:14). If he loved his master he could pledge himself in permanent servitude, and his ear would be pierced to show his commitment. But the most amazing law was that if a slave ran away from his master, he was not to be returned, but allowed to live free anywhere in Israel!

You shall not hand over to his master a slave who has escaped from his master to you. He shall live with you in any place he may choose… you must not mistreat him. (Deut. 23:15)

In every other law code, the penalty for not returning a slave was death. This radical reversal of ethics shows God’s great desire for freedom for his people. In fact, most of the time when God speaks of his people as his slaves, it is to protect their freedom and keep them from being enslaved to anyone else! For instance:

If a countryman of yours becomes so poor with regard to you that he sells himself to you, you shall not subject him to a slave’s service. For they are My avadim (servants/slaves), whom I brought out from the land of Egypt; they are not to be sold in a slave sale. (Lev. 25:42)

The year of Jubilee was also for that purpose — to redeem all of God’s people from bondage to anyone else, because they were his alone. If a person sold himself to a foreigner because of debt, the reason they were set free at the jubilee was because, “the sons of Israel are my avadim, they are my avadim whom I brought out from the land of Egypt. I am the Lord your God!” (Lev. 25:54-55). God set his people free to be his own, and for this reason they shall remain free.

Slaves of Christ

Many places in the New Testament use the image that just as God “purchased” or “redeemed” his people from slavery in Egypt, all who believe in Christ have also been “purchased”:

Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you, whom you have from God, and that you are not your own? For you have been bought with a price: therefore glorify God in your body. (1 Cor 6:19)

Were you called while a slave? Do not worry about it; but if you are able also to become free, rather do that. For he who was called in the Lord while a slave, is the Lord’s freedman; likewise he who was called while free, is Christ’s slave. You were bought with a price; do not become slaves of men. (1 Cor 7:22-23)

In this second verse, the ideas of being slaves but being free are once again interwoven. We have been redeemed from the evil masters of sin and death to become slaves of Christ, who actually won our freedom. When we are his, he will not let us be slaves to anything else.

Who will we serve?

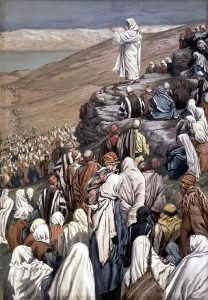

How do we live this out? In Exodus, after God redeemed his people, he gave them his Torah so that they could know how to serve him. God didn’t give them the law before he redeemed them and then expect them to earn their freedom — he redeemed them entirely out of grace.

Afterward, he gave them his law so that as his avadim, worshippers and servants, they would live in a way that would show the world his justice and love. In the same way, Jesus spent most of his earthly ministry giving us his Torah, his teaching, to show us how to serve him. Jesus’ laws didn’t negate the Torah, but rather he made it more encompassing and brought it to a higher level. If we say we worship Jesus, we must also serve him by doing his will.

It may come to us as news that every human is the servant of a greater master — whether an idolatrous god or our own appetites. We really don’t have a choice to be utterly free of any master, any more than we have a choice to quit a bad job in order to do absolutely nothing, because we need to support ourselves to live.

In the working world, we are “redeemed” from a bad employer when we find an employer who gives us fulfilling work and cares for our personal welfare. We move from one kind of serving to another kind of serving, not to be free from serving anything at all.

In the same way, we all need to choose our master, and in doing so, we should look at a potential master’s character to see whom we should choose. Will we serve pagan gods whose people lived in terror of them? Or will we serve a God who has great compassion for even the weakest of his people? Will we serve the demanding idols of success and money, who destroy our families and lives? Or will we serve our Master who sacrificed himself for our sins, and came not to be served, but to serve instead?

~~~~

1See the beginning verses of the books of Romans, Colossians, Titus, 2 Peter, Jude, and others. The writer of each book refers to himself as a doulos (“slave”) of Christ. Even though English translations often soften the word to “servant,” it really refers to a slave, not a servant.

2Understanding Genesis by Nahum Sarna (New York: Shocken Books, 1966), p. 16-18.

3See Christ’s Witchdoctor, by Homer Dowdy (Gresham, OR: Vision House, 1994) p. 7, 23, 46. This is the fascinating autobiography of a witchdoctor in a South American native tribe who came to Christ in the 1950s. He said that even though his tribe was prosperous and safe, they lived with constant fear of the spiritual world around them that they saw as mostly evil, and aimed to destroy them.

4Listening to the Language of the Bible, by Lois Tverberg & Bruce Okkema, (En-Gedi Resource Center, 2004) p. 21-22.

5See Exploring Exodus, by Nahum Sarna (New York: Shocken Books, 1986), p. 171-189. This is a fascinating comparison of the ancient near eastern laws to the Torah that shows the enormous ethical difference between the laws of Israel and other lands.

6Ibid, p. 179

7JPS Commentary on Exodus, by N. Sarna (New York: Jewish Publication Society, 1991), p. 125

Photos: Kyle Frederick on Unsplash, Color Crescent on Unsplash, Location of Mt. Sinai from bibleplaces.com, James Barr on Unsplash

Most Christians would define salvation as being allowed to enter heaven after death, which of course is focused on the afterlife. It is true that we will be saved from judgment, but the Bible also uses another picture of salvation that we rarely emphasize: salvation as a restored relationship with God, in this life. An unsaved person lives a life separated from God, because sin alienates him or her from God. As Paul says,

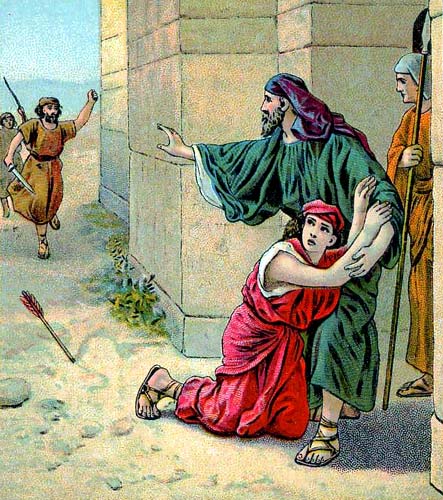

Most Christians would define salvation as being allowed to enter heaven after death, which of course is focused on the afterlife. It is true that we will be saved from judgment, but the Bible also uses another picture of salvation that we rarely emphasize: salvation as a restored relationship with God, in this life. An unsaved person lives a life separated from God, because sin alienates him or her from God. As Paul says, One thing is that our picture of God changes. If we only think of salvation as escaping hell, our idea of God is mainly that of an angry judge. In contrast, Jesus portrays God as a loving shepherd who searches for his sheep, or a loving father eager to see his son come home. This picture is of a God that actively wants to seek out his lost children, and bring them back into relationship with him. He loves us and wants us near him, he doesn’t just want to pardon us from our sins.

One thing is that our picture of God changes. If we only think of salvation as escaping hell, our idea of God is mainly that of an angry judge. In contrast, Jesus portrays God as a loving shepherd who searches for his sheep, or a loving father eager to see his son come home. This picture is of a God that actively wants to seek out his lost children, and bring them back into relationship with him. He loves us and wants us near him, he doesn’t just want to pardon us from our sins.