by Lois Tverberg

“For seven days eat bread made without yeast and on the seventh day hold a festival to the LORD. On that day tell your son, `I do this because of what the LORD did for me when I came out of Egypt.’ This observance will be for you like a sign on your hand and a reminder on your forehead that the law of the LORD is to be on your lips. For the LORD brought you out of Egypt with his mighty hand.” – Exodus 13:6, 8-9

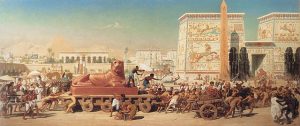

In Exodus 13, God told the Israelites to celebrate the Feast of Unleavened Bread every year in order to remember that the Lord brought them out of Egypt. They were to explain that the reason why they did it was because God redeemed them. By performing this ceremony each year, they would be continually mindful and grateful that God had redeemed them, and would teach their children about God’s love for them.

Interestingly, many of the laws of the Torah are rooted in the redemption from Egypt. Out of gratitude and obligation, when the Israelites realized what God had done for them, they should feel compelled to live differently:

Do not profane my holy name. I must be acknowledged as holy by the Israelites. I am

the LORD, who makes you holy and who brought you out of Egypt to be your God. I am

the LORD. – Lev. 22:31, 33If one of your countrymen becomes poor and is unable to support himself among you, help him so he can continue to live among you. I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of Egypt to give you the land of Canaan and to be your God. Lev. 25:35, 38

If one of your countrymen becomes poor among you and sells himself to you, do not make him work as a slave. Because the Israelites are my servants, whom I brought out of Egypt, they must not be sold as slaves. Lev. 25:39, 42

Each of the laws above is directly linked to God’s action of bringing the Israelites out of Egypt. They should help the poor live in the land because God gave them the land to live in. They shouldn’t hold other Israelites as slaves because God brought them out of slavery. Many other regulations are linked either directly or indirectly back to this act of God on their behalf.

Christians can learn a valuable lesson from this. When we think of our redemption in Christ and the price that he paid for us, it should compel us to live differently. We should forgive others, because he forgave us. We should humbly serve others, because Jesus humbled himself out of love to die for our sins. If we continually remind ourselves of how we’ve been loved, we will love others in the same way.

Photo: Willy Horsch

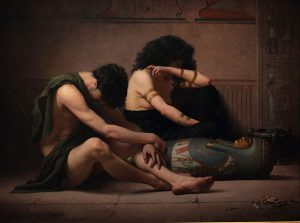

joy of the traditional Passover feast that was marred by the arguments over who was the greatest, and the ugly scene of finding out that Judas was a traitor. For Jesus, this night was one of great turmoil because he knew that it would be hours until Judas would bring the authorities to arrest him. While his disciples nodded off from plenty of wine and good food, he would sweat drops of blood waiting for his torture and execution.

joy of the traditional Passover feast that was marred by the arguments over who was the greatest, and the ugly scene of finding out that Judas was a traitor. For Jesus, this night was one of great turmoil because he knew that it would be hours until Judas would bring the authorities to arrest him. While his disciples nodded off from plenty of wine and good food, he would sweat drops of blood waiting for his torture and execution.

Why do they do this? Surprisingly, the Bible gives multiple explanations about the significance of eating unleavened bread. In Exodus 12:34, it says that it is to commemorate their rapid departure from Egypt, when they didn’t have time to let their bread rise. But in Deuteronomy 16:3, it is called the “bread of affliction” and it seems to be a reminder of the misery of their slavery. Or, it could understood as a picture of eating manna in

Why do they do this? Surprisingly, the Bible gives multiple explanations about the significance of eating unleavened bread. In Exodus 12:34, it says that it is to commemorate their rapid departure from Egypt, when they didn’t have time to let their bread rise. But in Deuteronomy 16:3, it is called the “bread of affliction” and it seems to be a reminder of the misery of their slavery. Or, it could understood as a picture of eating manna in

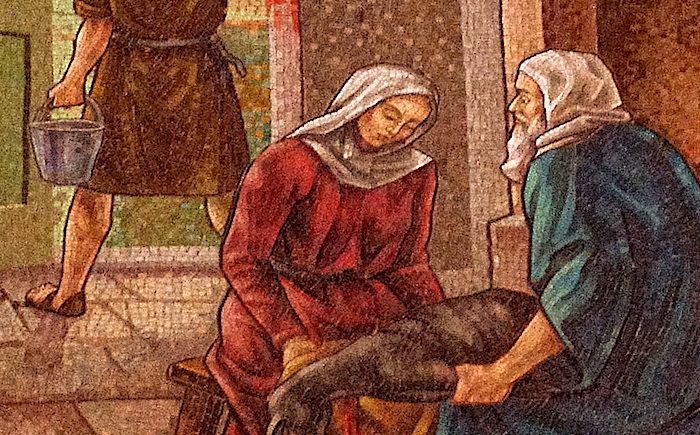

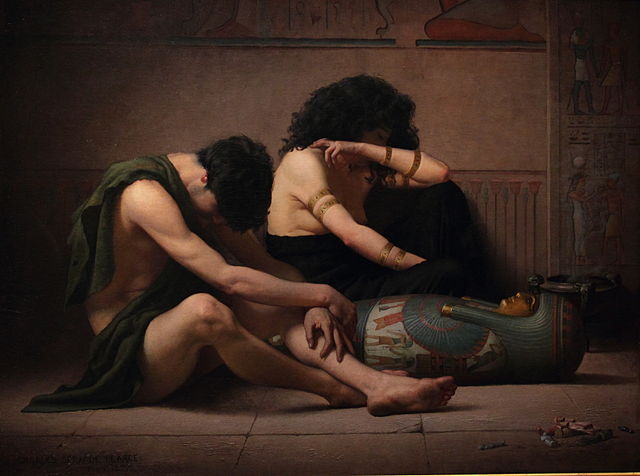

the bitterness of slavery, and parsley dipped in salt water to remember the tears that their ancestors shed. Along with dry, unleavened bread, these items are the only foods availaible through the long ceremony that precedes the Passover dinner, which begins very late. As they talk about God’s redemption of people from Egypt, the people relive that hardship for just an hour while they are hungry for dinner but have only dry bread and bitter herbs to eat. Finally, they feast on a meal of wine and meat and wonderful food, reminding themselves of the joy of God’s redemption.

the bitterness of slavery, and parsley dipped in salt water to remember the tears that their ancestors shed. Along with dry, unleavened bread, these items are the only foods availaible through the long ceremony that precedes the Passover dinner, which begins very late. As they talk about God’s redemption of people from Egypt, the people relive that hardship for just an hour while they are hungry for dinner but have only dry bread and bitter herbs to eat. Finally, they feast on a meal of wine and meat and wonderful food, reminding themselves of the joy of God’s redemption.

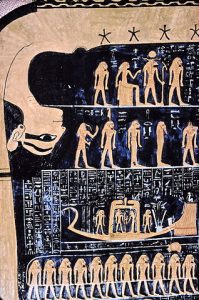

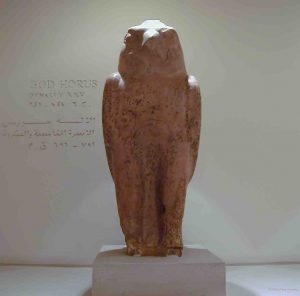

It is important to understand that in Hebrew, the word for “know,” yada, is more broad than in English, describing personal experience, not just intellectual knowledge. To “know” God in this sense is not just to have heard a name, but having awe for him from encountering his power directly. Pharaoh had no fear of this God because he had never experienced God’s power.

It is important to understand that in Hebrew, the word for “know,” yada, is more broad than in English, describing personal experience, not just intellectual knowledge. To “know” God in this sense is not just to have heard a name, but having awe for him from encountering his power directly. Pharaoh had no fear of this God because he had never experienced God’s power. The very first instruction that God gave the Israelites as they were leaving Egypt was to establish a new calendar that was utterly unlike the Egyptian calendar. This may not seem significant to us, but how we measure time is fundamental for how we look at life. Our calendars define the importance of the day to the entire culture, saying whether we should work, rest or worship, or think about some great event in our past.

The very first instruction that God gave the Israelites as they were leaving Egypt was to establish a new calendar that was utterly unlike the Egyptian calendar. This may not seem significant to us, but how we measure time is fundamental for how we look at life. Our calendars define the importance of the day to the entire culture, saying whether we should work, rest or worship, or think about some great event in our past.

him to somehow go convince Pharaoh to release the Israelites from slavery all on his own. What an impossibility that a stuttering 80-year old shepherd could do such a thing! Perhaps he imagined that God was telling him to raise up a rebellion who could demand release from Pharaoh. In his younger days when he was passionate for justice, maybe he could have done it, but not now. Surely God couldn’t use him.

him to somehow go convince Pharaoh to release the Israelites from slavery all on his own. What an impossibility that a stuttering 80-year old shepherd could do such a thing! Perhaps he imagined that God was telling him to raise up a rebellion who could demand release from Pharaoh. In his younger days when he was passionate for justice, maybe he could have done it, but not now. Surely God couldn’t use him.