by Lois Tverberg

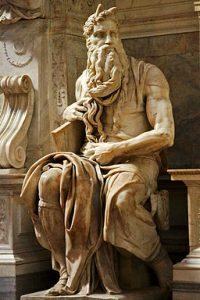

On Mt Sinai, God hides Moses in the cleft of a rock and passes by in all his glory. He then makes this fundamental declaration about his nature:

The LORD, the LORD, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin. Yet he does not leave the guilty unpunished; he punishes the children and their children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation. Exodus 34:6-7

This description of God, that He is “gracious and compassionate, slow to anger, abounding in lovingkindness…” is quoted nine times in the Old Testament. This description of God’s mercy comes up several times in the psalms (Psalm 86, 103, & 145 and others) and was probably part of many worship liturgies during Bible times.

Usually when this passage is quoted later in the Bible, the line about punishing children for the sins of the fathers is not included. This is satisfying to us, because we struggle with that line that seems quite unfair. There is actually a reason for it, if you look understand the culture and look closely at the text.

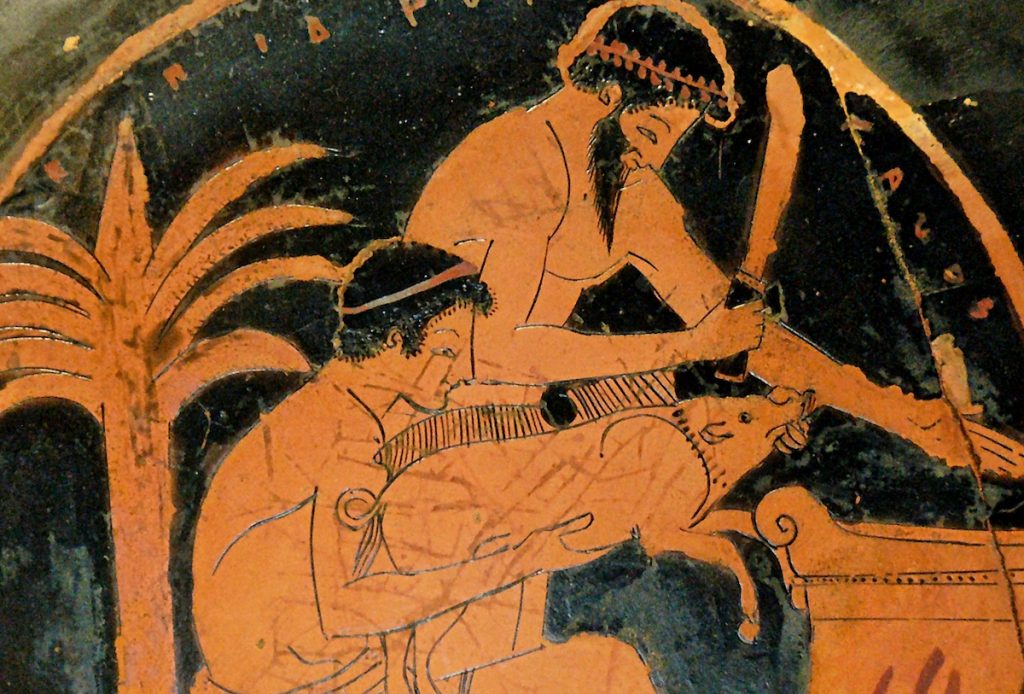

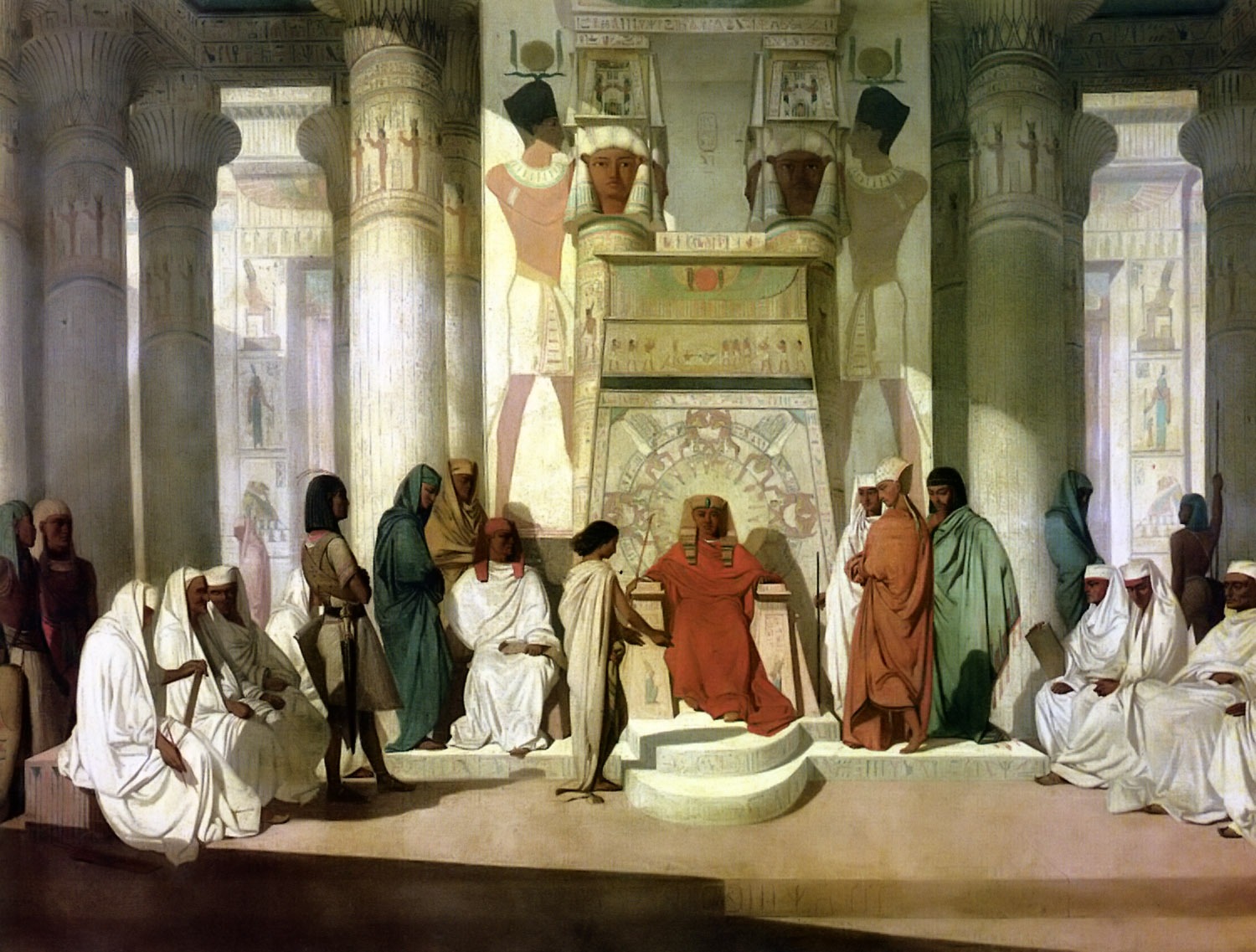

Tribal peoples like the Israelites saw their primary identity as being a part of a family or clan rather than as an individual. They worked together in everything and prospered or suffered together.

Tribal peoples like the Israelites saw their primary identity as being a part of a family or clan rather than as an individual. They worked together in everything and prospered or suffered together.

It was assumed that the group was responsible for the conduct of all of its members. If one sinned, especially the leader, they would all bear guilt and suffer misfortune for it. They saw themselves as a tightly-knit team. If one player fumbles the football, the whole team gets the penalty, of course. God’s statement about his justice extending to the third generation made complete sense in that world.

A New Idea in Ezekiel’s Time

In Ezekiel’s time, God pushes back on communal thinking that was pervasive in the ancient world. In Ezekiel 18, the people were quoting a proverb reflecting this kind of thought: ‘The fathers eat the sour grapes, but the children’s teeth are set on edge (Ezekiel 18:2). Surprisingly, God tells them not to quote this proverb anymore because he strenuously disagrees with punishing children for the sins of their parents!

This chapter in Ezekiel is actually one long argument against the idea that children should be punished for their parent’s sin. It sounds like the prophet has a hard time getting people to agree with him that an individual should be judged on his own terms, not in terms of the actions of his ancestors.

If a righteous man turns from his righteousness and commits sin, he will die for it; because of the sin he has committed he will die. But if a wicked man turns away from the wickedness he has committed and does what is just and right, he will save his life. Because he considers all the offenses he has committed and turns away from them, he will surely live; he will not die. (Ezekiel 18:25-27)

Therefore, O house of Israel, I will judge you, each one according to his ways, declares the Sovereign LORD. Repent! Turn away from all your offenses; then sin will not be your downfall. Rid yourselves of all the offenses you have committed, and get a new heart and a new spirit. Why will you die, O house of Israel? For I take no pleasure in the death of anyone, declares the Sovereign LORD. Repent and live! (Ezekiel 18:30-32)

So, we see that God himself sees that each person himself is accountable before him, and that it is unjust to condemn people for sins committed before their time.

Children who Carry on in Sin

How do we interpret Exodus 34:6-7 in the light of this passage? The picture of several generations being condemned for a sin may be describing the generational pattern of sin that we see in families. A father who abuses his wife often has sons who abuse their wives. Families do teach and reinforce patterns of sins (or righteousness) to their members that go on for generations. This is especially true in cultures which don’t send children to school, where children learn only from their parents and close relatives. Could it be that the children aren’t being punished for their parent’s guilt, but that the children have carried on in the family sins themselves?

The answer from Ezekiel is that the consequences of sin only extend to the generations that keep on in the sin of the ancestors. There is always hope, if the children will just repent and change their ways. God doesn’t take pleasure in the judgment of anyone, but bids us all to repent and live!

Photo: hannahpirnie and William Warby

To learn more about the communal style of thinking in the Bible, see chapter 7, “Reading the Bible as a ‘We'” in Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus (available in the En-Gedi Resource Center bookstore.)

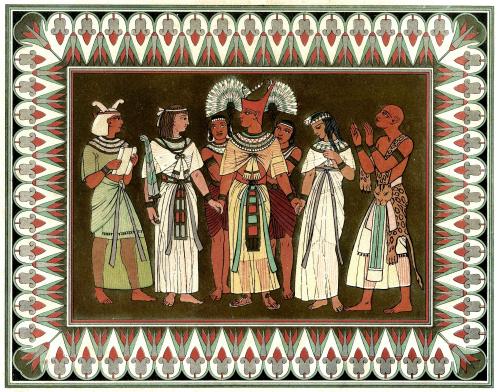

An interesting thing to note was that it seems that even though Joseph had great power in Egypt, he was still a slave even then and not free to leave. In the passage above, when Joseph wanted to travel to Canaan to bury his father, he had to ask permission. Scholars believe that the officials, chariots and horsemen who went with him were there partly to honor Jacob, but also to guard Joseph to make sure that he returned to Egypt.

An interesting thing to note was that it seems that even though Joseph had great power in Egypt, he was still a slave even then and not free to leave. In the passage above, when Joseph wanted to travel to Canaan to bury his father, he had to ask permission. Scholars believe that the officials, chariots and horsemen who went with him were there partly to honor Jacob, but also to guard Joseph to make sure that he returned to Egypt.

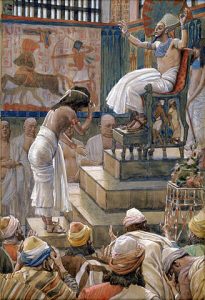

The story of the exodus from Egypt was a defining event in the life of Israel, when God heard their cries and saved them from their enemies. In Jesus’ time, it took on a heightened significance because the people were suffering under severe oppression of a foreign government, and they saw themselves as reliving the afflictions of Egypt. They prayed for a Messiah to come as a second Moses who would free them from bondage to the pagan ruler, just as he did before.

The story of the exodus from Egypt was a defining event in the life of Israel, when God heard their cries and saved them from their enemies. In Jesus’ time, it took on a heightened significance because the people were suffering under severe oppression of a foreign government, and they saw themselves as reliving the afflictions of Egypt. They prayed for a Messiah to come as a second Moses who would free them from bondage to the pagan ruler, just as he did before.

In the next weeks En-Gedi’s Water from the Rock series will focus on Exodus, specifically God’s redemption of the Israelites from Egypt. Christians generally don’t see this story as especially significant. But for thousands of years, Jewish readers have considered it a defining point their history, when God reached down into world events in an unprecedented way. The story of redemption is also central to the rest of the Scriptures, as the foundation of God’s relationship with the people of Israel. We can see the story’s critical importance just by noticing the many references that are made to it throughout the Bible. Here are just a few:

In the next weeks En-Gedi’s Water from the Rock series will focus on Exodus, specifically God’s redemption of the Israelites from Egypt. Christians generally don’t see this story as especially significant. But for thousands of years, Jewish readers have considered it a defining point their history, when God reached down into world events in an unprecedented way. The story of redemption is also central to the rest of the Scriptures, as the foundation of God’s relationship with the people of Israel. We can see the story’s critical importance just by noticing the many references that are made to it throughout the Bible. Here are just a few: