What did Jesus mean when he said that he “came not to abolish the Law but to fulfill it”? (Matthew 5:17)

Pastor Andy Stanley recently published an article in Christianity Today called “Jesus Ended the Old Covenant Once and for All” which is based on the idea that to “fulfill the Law” means “to bring it to an end.”1 An honest reader can’t avoid noticing that this interpretation seems strained. In just the next few verses, we find Jesus saying quite forcefully the very opposite. What is going on here?

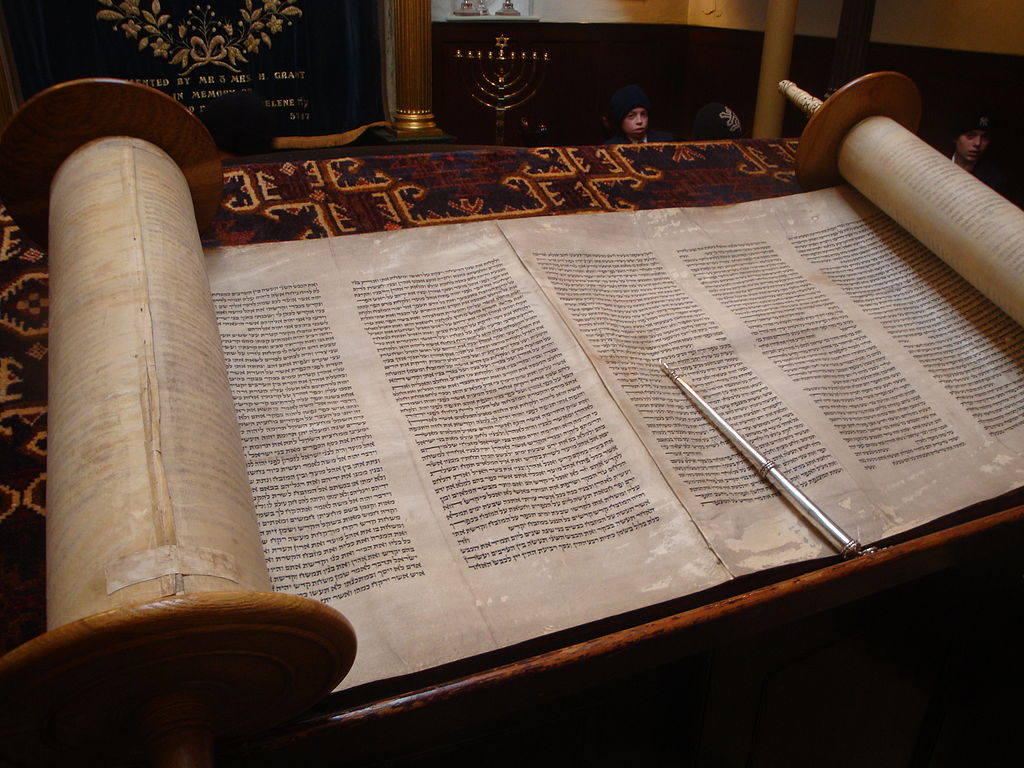

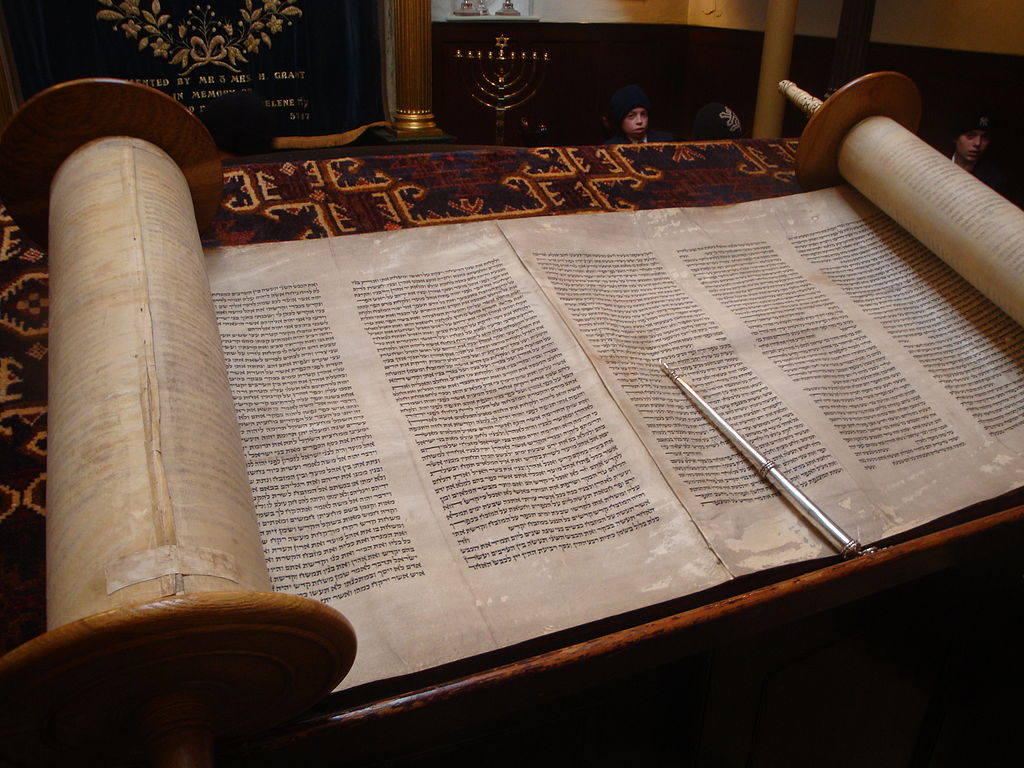

The key is that the phrase “fulfill the Law” is a rabbinic idiom. It is found several other places in the New Testament and in Jewish sayings too. Hearing it in context will shed light on its true meaning.

.

To Fulfill the Torah

The translation of “to fulfill” is lekayem in Hebrew (le-KAI-yem), which means to uphold or establish, as well as to fulfill, complete or accomplish. David Bivin has pointed out that the phrase “fulfill the Law” is often used as an idiom to mean to properly interpret the Torah so that people can obey it as God really intends.2

The word “abolish” was likely either levatel, to nullify, or la’akor, to uproot, which meant to undermine the Torah by misinterpreting it. For example, the law against adultery could be interpreted as only about cheating on one’s spouse, but not about pornography. When Jesus declared that lust also was a violation of the commandment, he was clarifying the true intent of that law, so in rabbinic parlance he was “fulfilling the Law.”

Imagine a pastor preaching that cheating on your taxes is fine, as long as you give the money to the church. He would be “abolishing the Law” – causing people to not live as God wants them to live.

Here are a couple examples of this usage from around Jesus’ time:

If the Sanhedrin gives a decision to abolish (uproot, la’akor) a law, by saying for instance, that the Torah does not include the laws of Sabbath or idolatry, the members of the court are free from a sin offering if they obey them; but if the Sanhedrin abolishes (la’akor) only one part of a law but fulfills (lekayem) the other part, they are liable.3

Go away to a place of study of the Torah, and do not suppose that it will come to you. For your fellow disciples will fulfill it (lekayem) in your hand. And on your own understanding do not rely.4 (Here “fulfill” means to explain and interpret the Scripture.)

Fulfilling the Law as Obedience

The phrase “fulfill the Law” has another sense, which is to carry out a law – to actually do what it says. In Jewish sayings from near Jesus’ time, we see many examples of this second usage as well, including the following:

If this is how you act, you have never in your whole life fulfilled the requirement of dwelling in a sukkah!5 (One rabbi is criticizing another’s interpretation of the Torah, which caused him not to do what it really intends.)

Whoever fulfills the Torah when poor will in the end fulfill it in wealth. And whoever treats the Torah as nothing when he is wealthy in the end will treat it as nothing in poverty.6 (Here it means “to obey” – definitely the opposite of “fulfill in order to do away with.”)

These two meanings of “fulfill” shed light on Jesus’ words on in Matthew 5:19:

…Anyone who breaks one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

Here the two actions of “practicing” and “teaching others to do the same” are an exact parallel to the two idiomatic senses of “fulfill.” In contrast, the words “break” and “teach others to break” are the idiomatic senses of “abolish.”

With this in mind, you can see that Matthew 5:19 parallels and expands on Jesus’ words about fulfilling and abolishing the Torah in Matthew 5:17. By understanding this idiom we see that Jesus was emphatically stating that his intention was to explain God’s Word and live it out perfectly, not to undermine or destroy it.

With this in mind, you can see that Matthew 5:19 parallels and expands on Jesus’ words about fulfilling and abolishing the Torah in Matthew 5:17. By understanding this idiom we see that Jesus was emphatically stating that his intention was to explain God’s Word and live it out perfectly, not to undermine or destroy it.

Why was Jesus emphasizing this point? Most likely because the Jewish religious leaders had accused him of undermining the Torah in his preaching. Jesus was responding that he was not misinterpreting God’s law, but bringing it to its best understanding.

Furthermore, if any of his disciples twisted or misinterpreted its least command, they would be considered “least” in his kingdom. Jesus’s entire ministry as a rabbi was devoted to getting to the heart of God’s Torah through what he said and how he lived.

Notice that on at least one occasion, Jesus leveled this same charge against the Pharisees. He accused them of nullifying the law to honor one’s mother and father by saying that possessions declared corban (dedicated to God) could not be released to support one’s elderly parents (Mark 7:11–12).

Certainly Jesus fulfilled the law by obeying it perfectly. But as a rabbi, he also “fulfilled” it by clarifying its meaning and enlightening people about how God truly wanted them to live.

Part II What Paul Said

In the past, the idea that “Christ brought the Law to an end by fulfilling it” has been the traditional rationale of why Christians are not obligated to keep the laws of the Old Testament.

We overlook the fact that in Acts 15, the early church declared that Gentiles were not obligated to convert to Judaism by being circumcised and taking on the covenant of Torah that was given to Israel. Instead they were told that they must simply observe the three most basic laws against idolatry, sexual immorality and murder, the minimal observance required of Gentile God-fearers.7

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).

Paul, of course, was zealous in saying that Gentiles were not required to observe the Torah when some insisted they become circumcised and take on other observances. He himself still observed the Torah, and proved it to James when asked to do so in Acts 21:24-26. Yet he still maintained that Gentiles were saved apart from observing it.

Paul supported this idea by pointing out that the Gentiles were being filled with the Holy Spirit when they first believed in Christ, not after they had become Torah observant (Gal. 3:2-5).

He also pointed out that Abraham did not observe the laws of the Torah that were given 400 years later, but was justified because of his faith. (Gal. 3:6-9)8 He concluded that all who believe are “Sons of Abraham” even though this very term was usually reserved for circumcised Jews.

Paul’s use of “Fulfill the Law”

An important part of this discussion is that Christians widely misunderstand the word “Torah,” which we translate as “law.” We associate it with burdensome regulations and legal courts. In the Jewish mind, the main sense of “Torah” is teaching, guidance and instruction, rather than legal regulation. Note that a torah of hesed, “a teaching of kindness” is on the tongue of the Proverbs 31 woman (Proverbs 31:26).

Why would torah be translated as law? Because when God instructs his people how to live, he does it with great authority. His torah demands obedience, so the word takes on the sense of “law.” But in Jewish parlance, torah has a very positive sense, that our loving Creator would teach us how to live. It was a joy and privilege to teach others how to live life by God’s instructions. This was the goal of every rabbi, including Jesus.

Why would torah be translated as law? Because when God instructs his people how to live, he does it with great authority. His torah demands obedience, so the word takes on the sense of “law.” But in Jewish parlance, torah has a very positive sense, that our loving Creator would teach us how to live. It was a joy and privilege to teach others how to live life by God’s instructions. This was the goal of every rabbi, including Jesus.

The question then becomes, if the Torah is God’s loving instructions for how to live, why would Gentiles be excluded from its wonderful truths? Surprisingly, in both Romans and Galatians, after Paul has spent a lot of time arguing against their need to observe the Torah, he actually answers this question by explaining how they can “fulfill the Law.” He says:

Let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another, for he who loves his fellowman has fulfilled the law. The commandments, “Do not commit adultery,” “Do not murder,” “Do not steal,” “Do not covet,” and whatever other commandment there may be, are summed up in this one rule: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Love does no harm to its neighbor. Therefore love is the fulfillment of the law. (Rom. 13:8-10)

For the whole law is fulfilled in one word, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (Gal. 5:14)

If Paul is using first idiomatic sense of “fulfill the Torah,” he is saying that love is the supreme interpretation of the Torah–the ultimate summation of everything that God has taught in the Scriptures.

Paul was reiterating Jesus’ key teaching about loving God and neighbor that says “All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments” (Matt. 22:40). The two laws about love are not just more important than the rest, they are actually the grand summation of it all.

About a century later, Rabbi Akiva put it this way: “Love your neighbor as yourself – this is the very essence (klal gadol) of the Torah.”9 Love is the overriding principle that shapes how all laws should be obeyed.

.

Love as Fulfilling the Torah

Paul also seems to be using the second idiomatic sense of “fulfill the Torah” (as obedience) to say that loving your neighbor is actually the living out of the Torah. When we love our neighbor, it is as if we have done everything God has asked of us. A Jewish saying from around that time has a similar style:

If one is honest in his business dealings and people esteem him, it is accounted to him as though he had fulfilled the whole Torah.10

The point of the saying above is that a person who is honest and praiseworthy in all his dealings with others has truly hit God’s goal for how he should live. He didn’t cancel the Law, he did it to the utmost!

Similarly, Paul is saying that when we love our neighbor, we have truly achieved the goal of all the commandments. So instead of saying that the Gentiles are without the law altogether, he says that they are doing everything it requires when they obey the “Law of Christ,” which is to love one another.

For him, the command to love is the great equalizer between the Jew who observes the Torah, and Gentile who does not, but who both believe in Christ. Paul says,

“For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision has any value. The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love.” (Galatians 5:6)

Part III Is Christ the End of the Law?

Paul tells us in Romans 10:4 that the “telos” of the law is Christ, which has been translated “Christ is the end of the law” (see NIV 1984). Much debate has occurred over this line. However, few have noticed the surprising way that telos is used elsewhere in the New Testament.

Believe it or not, we find two other places where the verb form of teleos (to end, complete) is used together with nomos (law) in the sense of in the sense of keeping or fulfilling (obeying) it!

Then he who is physically uncircumcised but keeps (teleo) the law will condemn you who have the written code and circumcision but break the law. (Romans 2:27)

If you really fulfill (teleo) the royal law according to the Scripture, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” you are doing well. (James 2:8)

Certainly in these two passages, the sense of teleo is not “terminate, bring to an end.”

Certainly in these two passages, the sense of teleo is not “terminate, bring to an end.”

Let’s also examine the other verb that is used in a similar context, pleroo (“to fulfill,” in the sense of filling up). This is what is used in Matthew 5:17, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill (pleroo) them.”1

Note how the verb pleroo is used in these other passages:

Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore love is the fulfilling (pleroo) of the law. (Romans 13:10)

For the whole law is fulfilled (pleroo) in one word: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (Galatians 5:14)

Like teleo, the sense of pleroo here is that of upholding the Torah rather than simply seeking its termination.

Christ is the Goal of the Torah

So, how should we read Romans 10:4? In light of the rest of Paul’s writing, I think it’s wise to take a two-handed approach. Scholars point out that while telos can mean “end,” it can also mean “goal” or “culmination.” They suggest that Paul’s wording in Romans 10:4 is deliberately vague, conveying two ideas at once. Christ is both the goal and the end of the Law, they conclude.

Christ is the climactic goal of the Torah, the living embodiment of the holiness and compassion toward which God was aiming. Jesus is the “Word made flesh.” He is the only one who has ever perfectly lived out the Torah.

Christ is the climactic goal of the Torah, the living embodiment of the holiness and compassion toward which God was aiming. Jesus is the “Word made flesh.” He is the only one who has ever perfectly lived out the Torah.

If the Torah is God’s teaching for how to live as his people, in what sense could it end? I’d point out two things. As Christians, we believe that Jesus took upon himself the punishment we deserve for our inability to keep God’s commands. As such, he brought the law to the end of its ability to separate us from God because of our sin. For that we rejoice!

Second, God’s policy for centuries had been to separate Israel from the influence of its pagan neighbors. He did this so that he could train his people properly, like a parent teaching a child (Galatians 3:24). In Christ, God gave a new command that went in the opposite direction. Instead of maintaining their distance, Jesus’ followers were to go into the world and make disciples of all nations (Matthew 28:19).

The instant Peter visited the first Gentile, the policy of separation collided with the new policy of outreach. According to Jewish law, Peter could not accept Cornelius’s hospitality because Gentiles were “unclean.” But God had given him a vision in which unclean animals were declared “clean.” (Acts 10:9-16)

With the guidance of the Spirit, the church ruled in Acts 15 that Gentile believers did not need to enter into the covenant that was given on Mount Sinai. The “dividing wall of hostility” that the Torah put up to keep the Gentiles away was brought to an end (Ephesians 2:14).

What about God’s Covenant with Israel?

The Torah also contains God’s covenant with Israel. Did Jesus bring this covenant to an end? Absolutely not, Paul exclaims! Just look at Romans 11:

I ask, then, has God rejected his people? By no means! …As regards the gospel, they are enemies for your sake. But as regards election, they are beloved for the sake of their forefathers. For the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable. Romans 11:1, 28-29

Paul mourns deeply for his Jewish brothers who have been alienated from God’s promises, and he longs for them to believe in their Messiah. He pictures Israel, the family of Abraham, as an olive tree that Gentiles have been grafted into. Some of Israel’s branches have been cut off, but he’s is optimistic that they can be grafted in again. In no way does Paul think of God’s covenant with Israel as nullified, though.

In Conclusion

As Gentiles, Christians are not obligated to keep the Mosaic covenant. It was given to Israel, not to the world. We are saved by faith because of Christ’s atoning death, not by keeping laws we were never given.

How then are we to live? Paul and the other New Testament writers spend most of their letters discussing this very subject. In Acts 15:21, the Jerusalem Council points out that that Gentile believers will hear Moses preached every weekend in the synagogue. Certainly they will learn how to live from hearing the Torah preached.

The Apostles knew that we can discover great wisdom within the Torah because Christ himself was the goal toward which it was aiming. This is our goal too—to be filled with the love and goodness of our Lord and Rabbi, Jesus.

~~~~~

Certainly much, much more could be said about these issues. My point is to share a few language and cultural insights that challenge our reading, not deal exhaustively with Pauline theology.

For an alternative perspective on Jesus and the Law, see chapter 12, “Jesus and the Torah” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 163-179. The rabbinic idiom “fulfilling the law” is discussed on p 176-77.

For an alternative perspective on Jesus and the Law, see chapter 12, “Jesus and the Torah” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 163-179. The rabbinic idiom “fulfilling the law” is discussed on p 176-77.

1 Andy Stanley elaborates on this interpretation in his new book Irresistible: Reclaiming the New that Jesus Unleashed for the World. (Harper Collins, 2018) His idea is that Christians need to distance themselves from the Old Testament because Jesus came to bring Judaism to an end. (Yes, he really said this.) He tries to soft-pedal this idea by saying that his true purpose is to make the Bible more inviting to seekers. But he uses classic Marcionistic and supercessionistic arguments to make his point, and ignores everything written by New Testament scholars in the past 50 years. This was a truly awful book that was painful to read.

2 See the chapter “Jesus’ Technical Terms about the Law” (pp. 93-102) in New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus: Insights from His Jewish Context, by David Bivin (En-Gedi Resource Center, 2007).

3 Mishnah, Horayot 1:3. The Mishnah is a compendium of Jewish law that contains sayings from 200 BC to 200 AD. This saying was very early, from before 70 AD.

4 Mishnah, Pirke Avot, 4:14.

5 Mishnah, Sukkot 2:7

6 Mishnah, Pirke Avot 4:9

7 See “Requirements for Gentiles” in New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus: Insights from His Jewish Context, by David Bivin, pp. 141-144. The three commandments against idolatry, sexual immorality and murder were considered the three most heinous sins, and also sins that Gentiles were particularly prone to commit.

Scholar David Instone-Brewer points out that “strangling” was likely a reference to infanticide, which was practiced by Gentiles but abhorrent to Jews. See the article, “Abortion, What the Early Church Said.”

8 See the article “Family is Key to the “Plot” of the Bible.”

9 Rabbi Akiva, (who lived between about 50-135 AD); B. Talmud, Bava Metzia (62a). Also see the article, The Shema and the First Commandment.

10 Mekhilta, B’shalach 1 (written between 200-300 AD).

Bible quotations are from the ESV. Compare translations of Romans 10:4 here.

Image credits – Wikipedia, Herman Gold, Glen Edelson Photography, József Molnár, Stephen Baker, Matt Botsford, Kate Bergin.

Back when I was in college, I took part in a performance of Handel’s Messiah. Having grown up in a Christian home that mostly only read the Gospels and Paul, I was puzzled by the haunting lyrics of one chorus. It sounded like it was straight out of the New Testament, but I had never heard it before. I was moved to tears by each line:

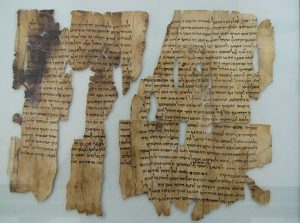

Back when I was in college, I took part in a performance of Handel’s Messiah. Having grown up in a Christian home that mostly only read the Gospels and Paul, I was puzzled by the haunting lyrics of one chorus. It sounded like it was straight out of the New Testament, but I had never heard it before. I was moved to tears by each line: For many years, I was quite thrilled at my Bible study discovery. If I had known my Old Testament better, maybe it would not have been that special. Then I began to learn more about archeology and the discovery of the the Dead Sea Scrolls. In 1948, many ancient scrolls and fragments were uncovered in the Essene community of Qumran, in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea in Israel.

For many years, I was quite thrilled at my Bible study discovery. If I had known my Old Testament better, maybe it would not have been that special. Then I began to learn more about archeology and the discovery of the the Dead Sea Scrolls. In 1948, many ancient scrolls and fragments were uncovered in the Essene community of Qumran, in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea in Israel.

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).