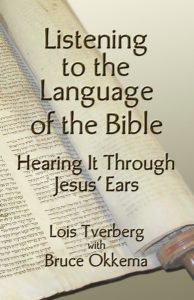

by Lois Tverberg

Anyone who does much study of the Bible will notice that often it speaks in odd-sounding, poetic phrases. Some translations of the Bible interpret these for readers, but others leave them quite literal and hard to understand.

Anyone who does much study of the Bible will notice that often it speaks in odd-sounding, poetic phrases. Some translations of the Bible interpret these for readers, but others leave them quite literal and hard to understand.

Why does the Bible have such an odd “accent”? Because it comes to us from languages and cultures different from ours. If we want to hear the Bible for what it really is saying, we need to get a sense for its idioms and thought patterns.

This is especially true as we read the Old Testament, which reflects an ancient culture very different from our modern, Western mindset. We can avoid misunderstanding when we realize that even words that have been translated literally may have originally carried a different connotation than they do in English.

Besides making the Bible clearer, hearing its words as they were originally meant is a tremendously enriching experience, giving us wonderful new insights into God’s word.

Rich Hebrew Words

The Old Testament was written in Hebrew, and even though the New Testament was written in Greek, it was written almost entirely by Jews growing up in a Hebrew-speaking, Semitic-thinking culture. Because of this, its ideas come out of a Hebraic world-view. Having a sense for the style of the Hebrew language is therefore very important for understanding the Bible and gives us clues on the thinking patterns of its writers.

Hebrew has a small vocabulary, and each word often has a greater depth of meaning than our corresponding word, to describe many related things. For example, the Hebrew word for house, beit, can mean house, temple, family or lineage. Also, the Hebrew language lacks abstractions, and uses physical pictures to express abstract ideas, like being “stiff-necked” (stubborn) or “heart was lifted up” (was prideful), which sound poetic to us.

Hebrew also often uses the identical word to describe a mental activity as the physical result of the activity. For example, to listen can mean just to listen, but it usually means to obey the words you hear, which is the result of listening. I have found it amazingly useful in my study of the Bible to get a sense of these wider meanings, so that I can get a fuller understanding of what this odd poetry really means.

Here are a few examples of the idiomatic meanings words can have in Hebrew, in addition to their literal meaning in English.

Name – Authority, reputation, essence, identity

“In the name of Jesus” means, “by the authority of Jesus,” or “for the sake of Jesus.” Often it speaks about the temple as where “God’s Name dwells,” which really means his authority and presence. See the examples below:

He who receives a prophet in the name of a prophet shall receive a prophet’s reward; and he who receives a righteous man in the name of a righteous man shall receive a righteous man’s reward. (Meaning, because they know the person’s identity as a prophet or righteous man) (Matt. 10:41)

But as many as received him, to them he gave the right to become children of God, even to those who believe in his name. (Meaning, those who believe in Jesus’ identity as the Son of God) (John 1:12)

Son – Descendant, including grandsons and later descendants, disciples

The Israelites, both male and female were called “sons of Israel,” and the Messiah was supposed to be a “son of David.” It was assumed that descendants would share the character of their forefathers too, so a “son of David” would be expected to be kingly and powerful. Jesus says peacemakers will be called “sons of God,” because they are like God in character (Matt 5:9)

House – Family, descendants, disciples, possessions, the temple

House – Family, descendants, disciples, possessions, the temple

God plays on the multiple meanings of the word when King David asks if he can build a “house” for God (a temple) and God answers that he would build a “house” for David, meaning a kingly lineage that will never end (see 1 Chron. 17:4, 10). We are God’s house: his temple, but also his family.

Law (Torah) – Instruction, guidance, teaching – comes from the word for “to point, aim, or guide“

In Jewish translations it is usually rendered as “instruction” or “teaching.” It has a very positive understanding in terms of being God’s word that contains his guidance for living. This is one of the most misunderstood of words in church tradition, where the “Law” has taken on a negative idea of a legalistic body of oppressive rules.

Visit – Pay attention to, come to the rescue of, bring to judgement (a very wide range of meaning indeed!)

Then Joseph said to his brothers, “I am about to die. But God will surely visit you (come to your aid) and take you to the land he promised on oath to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.” (Gen. 50:24)

What is man that you are mindful of him, the son of man that you visit (take notice of) him (Ps. 8:5)

Now go, lead the people to the place I spoke of, and my angel will go before you. However, in the day when I visit, I will visit their sin upon them. (Meaning, I will pay attention to their sin and punish them.) (Ex. 32:34)

Interestingly, Jesus seems to be playing on this when, at the cleansing of the temple, he says,

“For the days will come upon you when your enemies will throw up a barricade against you, and surround you and hem you in on every side, and they will level you to the ground and your children within you, and they will not leave in you one stone upon another, because you did not recognize the time of your visitation.” (Luke 19:43-44)

The “time of their visitation” could mean the time God has come to their rescue in the person of Christ, but for those who ignore him, it will be the source of their punishment, when God “visits” their sins on them through the destruction of the temple.

Listen, hear – Take heed, be obedient, do what is asked

The Shema is the first word of the Jewish “Pledge of Allegiance,” and it means “Hear.” But really, it means “take heed” or “obey.” In fact, almost every place we see the word “obey” in the Bible, it is translated from the word shema, to hear. When Jesus says, “He who has ears to hear, let him hear,” he is calling us to put his words into action, not just listen.

Remember – Do a favor for, come to the aid of

After the flood, God “remembered” Noah and dried up the waters, meaning that he rescued him, and Hannah says God “remembered” her when she conceived — he did her a favor. The Psalms often plead with God to “remember his people” in the sense of coming to their rescue.

Forget – Ignore, not act on

The cupbearer “forgot” Joseph — actually meaning he ignored his request. God “forgets” our sins — meaning he will never hold them against us, not that his omniscient mind actually loses the memory of them.

Know – Have a relationship with another person, even intimately, to care for another

Adam knew his wife Eve, and she conceived, and bore Cain. (Gen. 4:1)

The righteous man knows (cares for) his animals… (Prov. 12:10)

I will give them a heart to know Me, for I am the LORD; and they will be My people, and I will be their God… (Jer. 24:7)

Having a sense for this way of speaking will be a lot of help to those who want to explore their meaning in passages. Newer translations (ESV, NIV, etc.) tend to explain these words, while older translations (King James) will use a direct, literal meaning.

While it is nice to not struggle to understand, often the poetry and wordplays and parallels between passages are obscured in less literal translations. My recommendation is to have more than one translation available, and compare to see the range of interpretations for passages.

One thing we should notice about Hebrew verbs is that they tend to stress action and effect, rather than just mental activity. Our own Western frame of reference stresses that our intellectual life is most important, while the Hebrew assumes that actions will result from it. In the Hebrew sense, if you “remember” someone, you will act on their behalf. If you “hear” someone, you will obey their words. If you “know” someone, you will have a close relationship with them.

When you read a word that sounds like it is talking about mental activity, stop and think in terms of the action that is expected to result. If you are reading the scripture to apply to your own life, make sure that it goes beyond thought to concrete action: that you are a doer of the word, and not a hearer only.

~~~~

Photos: Nicole Honeywill on Unsplash, Scott Webb on Unsplash, Acabashi [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Any student of language knows that each one frames the world in different ways. Often the same word is used for more than one thing that the culture considers equivalent, but distinguishes when differentiation seems important.

Any student of language knows that each one frames the world in different ways. Often the same word is used for more than one thing that the culture considers equivalent, but distinguishes when differentiation seems important. The word hokmah describes the ability to function successfully in life, whether it is by having the right approach to a difficult situation, or the ability to weave cloth. It is practical and applicable to this world, not just otherworldly.

The word hokmah describes the ability to function successfully in life, whether it is by having the right approach to a difficult situation, or the ability to weave cloth. It is practical and applicable to this world, not just otherworldly.