by Lois Tverberg

As we read the story of Passion week, we often bump into scenes that don’t quite make sense to us. Why did Jesus choose his last week to overturn the tables in the temple courts? Did the same crowd love Jesus on Palm Sunday when he rode into Jerusalem, then call for his execution one week later? At Jesus’ trial, why was Jesus accused of saying that he would destroy and rebuild the temple?

A few pieces of historical data can shed a lot of light on this story. Understanding who was accusing Jesus, and what their expectations were for the Messiah can help answer our questions and link together events that seem unrelated. We will also find that Jesus fulfilled his role as Messiah in ways that we may never have considered before.

Important Data to Consider

A detail that is little known, but critical for understanding Jesus’ last week, was the corruption of the temple priesthood that existed in Jesus’ time. In Israel the temple was the heart and soul of the faith of the people of Israel, understood to be where God’s very presence dwelled.

A detail that is little known, but critical for understanding Jesus’ last week, was the corruption of the temple priesthood that existed in Jesus’ time. In Israel the temple was the heart and soul of the faith of the people of Israel, understood to be where God’s very presence dwelled.

In the hundred years preceding Jesus’ ministry, however, the priestly leadership had become extremely corrupt. Throughout the history of Israel, high priests were chosen by lot from among the Levites. Herod felt threatened by the power of the priesthood, so he ignored biblical law and appointed the high priest himself. The position was subsequently bought with bribes from wealthy Sadducean families, who agreed to keep peace with Rome in exchange for wealth from the temple tithes and the sale of sacrificial animals.

The priestly family that had been in power for many years in Jesus’ time was the house of Annas (or, Ananias), who himself served for 9 years and then appointed several sons and one son-in-law, Caiaphas. This family was extremely wealthy and corrupt, functioning much like a “mafia.”1 The “godfather” was Annas, who controlled the position even when his sons were given the title of High Priest.

The family of Annas owned the flocks from which the sacrificial animals had to come. They also controlled the money-changing tables at the Temple, which were called “booths of Annas.” They charged greatly inflated prices on sacrificial animals, extorted money, and stole funds intended to support other priests who had no other income.2

The Jews of Jesus’ time hated this corruption, and one group, the Essenes, entirely divorced themselves from worship at the temple, considering it to be defiled. John the Baptist also spoke against the priesthood, saying that the Messiah would come to clear “his threshing floor” — an allusion to the temple, which David first established on a threshing floor3 (Matt 3:12, 2 Sam 24:13).

Jesus’ Conflict with the Priests

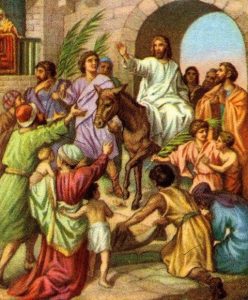

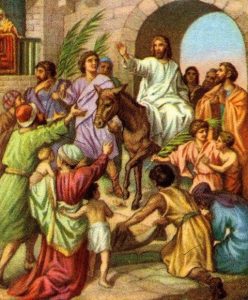

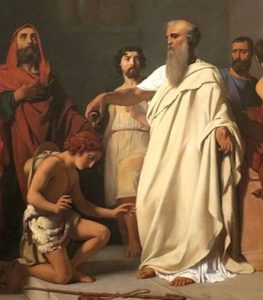

When Jesus, the brilliant yet humble rabbi rode into Jerusalem on a donkey, he employed a king’s entrance like what was foretold in the scriptures (1 Ki. 1:38-40, Zech. 9:9). He was proclaiming himself as the Messiah, God’s anointed king.

The first thing Jesus did after his triumphal entry was to enter the temple courts and drive out the sellers. Jesus’ denunciation of the sellers was much more than just wanting the worship area to be free from commerce. He was aiming at the high priest’s family itself, as he assaulted the “booths of Annas” where they were getting rich from temple worship by forcing faithful Jews to buy their overpriced sacrifices.

If Jesus was speaking rabbinically, his words to the sellers carried much more power than their literal meaning. He said, “My house is to be a house of prayer, but you have made it a den of thieves” (Luke 19:46), which is an allusion to Jeremiah 7:11, where God was denouncing the wicked religious leaders of Jeremiah’s era. God had said that the temple had become a “den of thieves,” and if they didn’t repent he would destroy it.4

Rabbis frequently hinted to part of a scripture to make a strong statement that referred to the rest of the passage. In fact, during Jesus’ last week, he alluded to many passages about the destruction of the temple, as well as openly prophesying about it. He seemed to be linking the coming destruction of the temple in 70 AD with the corruption of the priesthood of his day.5

At one point during Jesus’ last week, he told a very pointed prophetic story against the priests, the “Parable of the Vineyard” in Luke 20:9-16. In that story, wicked tenants refused to give their landowner his money, and killed his servants and finally his son. The landowner responds by having them put to death.

At one point during Jesus’ last week, he told a very pointed prophetic story against the priests, the “Parable of the Vineyard” in Luke 20:9-16. In that story, wicked tenants refused to give their landowner his money, and killed his servants and finally his son. The landowner responds by having them put to death.

This story was specifically aimed at the priestly leaders, whose corruption was famous.6 They were robbing God, the landowner, and killing those God sent to enforce his law, including his Son, Jesus. Once again, it pointed toward the priests being destroyed because of their sin. The religious leaders realized that they were being rebuked and wanted to arrest him immediately. Sadly, this parable has been thought by many to be aimed at the Jews in general, rather than the temple leadership of Jesus’ time.

The Passover Plot

When Jesus entered Jerusalem and made his rightful claim to be the Messianic King, he set into motion the events that he knew would lead to his death. He was greatly popular with the people, and because of that, the religious leaders were afraid all the people would follow him (John 11:48). They were obligated to squash all rebellion and keep the peace, so that the Romans would allow them to keep their positions of power.

Moreover, by challenging the temple “racket,” Jesus was bringing the wrath of the powerful priestly syndicate down on his head. The religious leaders couldn’t touch him when he was surrounded by large crowds of followers, but they wanted to end his life. They needed someone who knew how to find him at night when he was in his secluded camp outside of the city, away from the crowds.

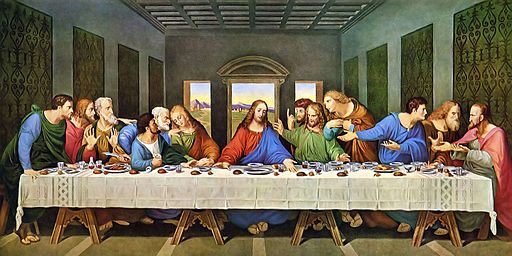

Choosing the night of Passover was a perfect scheme, because every religious Jew would be in his home celebrating the Passover meal that started at sundown. The celebration usually went until almost midnight, and most people would immediately go to bed after having a large meal with several glasses of wine.

The streets would be deserted of the throngs that had come for the feast, and it would be easy for Judas to lead the soldiers to where they could seize Jesus. The arrest and trial of Jesus occurred well after midnight on Passover night, because the whole city was asleep, except Jesus’ enemies who needed to convict him before the crowds heard about it.

Who rejected Jesus, and who didn’t?

An important conclusion from this is that the people who called for Jesus’ crucifixion were not the same crowd as the one that hailed him as Messiah the week before. The council that met at such a late hour on a major holiday for a hasty conviction was likely not the entire Sanhedrin, but a quickly assembled group of sympathizers.

The mob that gathered early Passover morning to shout “crucify” consisted of the Sadducean priests, the elders and their supporters. They were the ones who demanded Jesus to be crucified and Barabbas released, because Jesus had offended them by denouncing their corruption.

Later, a large number of people came out to follow him to the cross and mourn for his death, but those who taunted him were the priests and Roman soldiers. Jesus was as popular with the masses at his death as he was one week earlier!

Later, a large number of people came out to follow him to the cross and mourn for his death, but those who taunted him were the priests and Roman soldiers. Jesus was as popular with the masses at his death as he was one week earlier!

Historically, the stories of Jesus’ Passion have been read with the understanding that the Jews as a whole were acting together to destroy Jesus. This may be because in John’s account, he frequently uses the term “the Jews,” which we assume refers to the whole nation. More likely, as a Jew himself, he was speaking of the Jewish leaders who opposed Jesus, or perhaps the “Judeans” — the Jews who lived in and around Jerusalem who rejected the Galilean rabbi.7

John also reported that Jesus had great popularity — so much so that the priests feared that the whole nation would believe in him (John 11:48), and that many even among the leaders believed in him (John 12:42)! By knowing more about the issues and populations of first century Judaism, we can see that those responsible for his death were a few of those in power who saw his kingship as a threat to their own corrupt empires.

We can see that Jesus’ movement was far from rejected by the Jews. Fifty days after Jesus’ resurrection, on Pentecost, three thousand people became believers, and according to Acts 21:20, soon tens of thousands of Jews would believe in him. One Jewish scholar believes that as many as 50,000 people, including many Pharisees and priests, became believers in Jerusalem alone.8

This was a substantial proportion of the city’s population of that time, suggesting that a very large movement in Judaism was the foundation of the early church. We should therefore read the words in the New Testament about the “Jewish rejection of Jesus” as wondering why every single Jew did not believe in him, rather than that the Jewish people as a whole rejected him. Within a hundred years, the church had become largely Gentile, but the early church was almost entirely Jewish for many years.

In the book of Acts, we read that Annas and the high priests also continued their persecution of Jesus’ followers for several years. They first commissioned Paul to kill members of the church (Acts 9:14, 26:10-12), then later put him on trial for being a believer himself (Acts 25:2).

They also were responsible for the death of Stephen (Acts 6:12 ) and later, James, the brother of Jesus.9 The house of Annas and the rest of the Sadducean aristocracy that controlled the temple finally came to an end when Jerusalem was destroyed in 70 AD, just as Jesus predicted.

Prophecies Fulfilled

Of course, God ultimately was fully in control, allowing evil men to put to death his righteous Son. Even the details that we may not have known are actually part of what was prophesied about the coming of the Messiah, and show how God worked out his plan. For example, one of the roles of the Messiah was to enter the temple and purify the priesthood. Malachi says,

“See, I will send my messenger, who will prepare the way before me. Then suddenly the Lord you are seeking will come to his temple; the messenger of the covenant, whom you desire, will come,” says the LORD Almighty But who can endure the day of his coming? Who can stand when he appears? For he will be like a refiner’s fire or a launderer’s soap. He will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver; he will purify the Levites and refine them like gold and silver. (Mal. 3:1-3)

This may explain why, as soon as Jesus formally announced his Messiah-ship by entering Jerusalem on a donkey, he entered the temple and prophetically cleansed it.

This may explain why, as soon as Jesus formally announced his Messiah-ship by entering Jerusalem on a donkey, he entered the temple and prophetically cleansed it.

Another place we see fulfilled prophecy is in the words of Jeremiah 23, which were also about the corrupt leadership of Israel that caused God to destroy the temple in Jeremiah’s time. Here they are called evil “shepherds”:

“Woe to the shepherds who are destroying and scattering the sheep of My pasture!” declares the LORD. Therefore thus says the LORD God of Israel concerning the shepherds who are tending My people: “You have scattered My flock and driven them away, and have not attended to them; behold, I am about to attend to you for the evil of your deeds,” declares the LORD. “Then I Myself will gather the remnant of My flock out of all the countries where I have driven them and bring them back to their pasture, and they will be fruitful and multiply. I will also raise up shepherds over them and they will tend them; and they will not be afraid any longer, nor be terrified, nor will any be missing,” declares the LORD. “Behold, the days are coming,” declares the LORD, “When I will raise up for David a righteous Branch; and He will reign as king and act wisely and do justice and righteousness in the land. (Jer. 23:1-6)

Here the coming of the Messiah is linked to the destruction of corrupt leaders. This is also true in Ezekiel 34:1-23, where God himself regathers his sheep, punishes the “shepherds” that are abusing and robbing the people, and sends the Messiah to reign over them. Now Jesus’ words in John 10 take on new depth, as we see who the “thieves and robbers” really were:

So Jesus said to them again, “Truly, truly, I say to you, I am the door of the sheep. All who came before Me are thieves and robbers, but the sheep did not hear them. I am the door; if anyone enters through Me, he will be saved, and will go in and out and find pasture. The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy; I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly. I am the good shepherd; the good shepherd lays down His life for the sheep… I have other sheep that are not of this sheep pen. I must bring them also. They too will listen to my voice, and there shall be one flock and one shepherd.” (John 10:7–11, 16)

Here, the “good shepherd” is the one who opposes the bad shepherds and gathers his people together, the faithful Jews who recognized him as their true King. It also included the Gentiles who are “not of this sheep pen.” Jesus was alluding to the passages in Jeremiah and Ezekiel to explain his mission.

Jesus also prophesied that the temple would be destroyed and another built without hands (John 2:19, possibly quoted in Mk: 14:58). In one sense, he was speaking about his body, but it is possible that he was also speaking about the church. When the Spirit was poured out on the believers on the day of Pentecost, God’s Spirit that filled the temple had found its new “house.”

The early church understood this to be the case, speaking often of the believers as being God’s temple (See Eph. 2:19–22, 1 Pet. 2:4-5). This too was a fulfillment of prophecy, as Jesus was the true “Son of David,” who, like Solomon, would be commissioned to build the temple.10 In Zech. 6:12-13, it also speaks of the Messiah as the one who would build the temple, sit on the throne, and be its new High Priest. Once again Jesus fulfilled prophecy in a way that we may not have realized.

Conclusion

It is amazing how a few more historical details about first century Judaism can shed new light on the story of Jesus’ Passion and the founding of the early church. Rather than undermining the power of the story, seeing its context shows even greater ways that God used Jesus’ death and resurrection to accomplish his plan.

We see that the Jewish people as a whole were not responsible for his execution: although of course we all are to blame for Jesus’ death for our sins. From the beginning of history, God had planned to use the corruption of Jesus’ time to establish Jesus as King and High Priest of a kingdom that would have no end.

~~~~

1 Flavius Josephus The Wars of the Jews IV, 3.7.

2 Brian Kvasnicka, Vying with Roman-allied Priests: Tribute and Tithe-evasion in First-century Roman Judea, presentation at the 2004 Society for Biblical Literature annual meeting.Also, Josephus, Antiquities 20.9.2 (205-207): “but as for the high priest Ananias, … he was a great hoarder up of money; he also had servants who were very wicked, who joined themselves to the boldest sort of the people, and went to the thrashing floors, and took away the tithes that belonged to the priests by violence, and did not refrain from beating such as would not give these tithes to them. So the other high priests acted in the like manner, as did those his servants without anyone being able to prohibit them; so that [some of the] priests, that of old were wont to be supported with those tithes, died for want of food.”

3 See Randall Buth and Brian Kvasnica, “Temple Tithes and Tax Evasion: The Linguistic Background and Impact of the Parable of the Vineyard, the Tenants and the Son,” in Jesus ‘ Last Week: Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels -Volume One (ed. R. Steven Notley et al.; Leiden: Brill, 2006), 65-73.

4 See the En-Gedi article “Hearing Jesus’ Hidden Messages.”

5 Jesus’ final week is full of scripture allusions to the corruption of the temple and its coming destruction. For example, “the stones will cry out” (Lk 19:40) refers to Hab. 2:11; “you did not know the way of peace” (Lk 19:42) refers to Is. 59:8; “he whom the stone falls” (Lk 20:18) refers to Dan. 2:34 -35, 44; and “the dry tree” (Lk 23:31) refers to Ezek. 20:47. Use a very literal translation (King James or New American Standard) to compare these texts, and read the OT scripture reference in its greater context.

6 Brian Kvasnicka, The Climactic Economic and Halachic Tensions in Jesus’ Last Week: The Parable of the Vineyard Tenants and Son and the Temple Demonstration, presentation at the 2004 Society for Biblical Literature annual meeting.

7 An excellent further reference is Misconceptions about Jesus and the Passover, a lecture series by Dwight Pryor, available at www.jcstudies.com.

8 Shmuel Safrai, as quoted by Dwight Pryor in Misconceptions about Jesus and the Passover.

9 Flavius Josephus, “Antiquities” 20.9.1.

10 See the En-Gedi article “Builder of the House.”

Photos: Berthold Werner [Public domain], David Köhler on Unsplash, Unknown publisher of Bible Card [Public domain]

In the past couple weeks, I have been reminded of an image from one of the traditions of Sukkot, the feast of tabernacles, that will be celebrated next week. God tells his people to build booths and live in them for seven days, in order to remember how he brought them out of Egypt and kept them safe in the booths they lived in. This was to remind them of how God took care of them so that their feet did not swell and their clothes did not wear out. To this day, Jewish people have observed the tradition of building a sukkah.

In the past couple weeks, I have been reminded of an image from one of the traditions of Sukkot, the feast of tabernacles, that will be celebrated next week. God tells his people to build booths and live in them for seven days, in order to remember how he brought them out of Egypt and kept them safe in the booths they lived in. This was to remind them of how God took care of them so that their feet did not swell and their clothes did not wear out. To this day, Jewish people have observed the tradition of building a sukkah.

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most important day of the year for Jews. It begins before sunset the night fore, and includes a 25 hour fast from both food and water, and ceasing of all work. It is a day set aside to “afflict the soul,” to ask for atonement for the sins of the past year. Even Jews who otherwise are not observant will observe this day.

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most important day of the year for Jews. It begins before sunset the night fore, and includes a 25 hour fast from both food and water, and ceasing of all work. It is a day set aside to “afflict the soul,” to ask for atonement for the sins of the past year. Even Jews who otherwise are not observant will observe this day.