by Lois Tverberg

Throughout Jesus’ time on earth, the focus of his teaching was the Kingdom of God. In fact, he says, “I must preach the good news of the kingdom of God to the other towns also, because that is why I was sent” (Luke 4:43). Even though Jesus’ ministry focused on it, many things he says about it leave us scratching our heads. Is it now or in the future? Why is it so important to him? Why is it good news? Once again, having a knowledge about Jesus’ first century Hebrew culture will greatly clarify his teaching.

Kingdom of Heaven & Kingdom of God

First of all, we read two different phrases in the gospels: “kingdom of heaven” and “kingdom of God.” In Matthew, “kingdom of heaven” is used, while in Mark and Luke, “kingdom of God” is used. This is because in Jesus’ day, and even now, Jews show respect for God by not pronouncing his  name, but substituting another word. For example, the prodigal son says, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and in your sight” (Luke 15:21). So, Matthew is preserving the culturally-correct “kingdom of heaven” while Mark and Luke are explaining that “heaven” is a reference to God. The actual words that came out of Jesus’ mouth were probably “Malchut shemayim” (mahl-KUT shuh-MAH-eem), which was a phrase common in rabbinic teaching in his day. Malchut, which we translate as “kingdom,” actually refers more to the actions of a king — his reign and authority, and anyone who is under his authority. Shemayim is Hebrew for “heavens.” A simple way of translating it would be “God’s reign,” or “how God reigns” or “those God reigns over.”

name, but substituting another word. For example, the prodigal son says, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and in your sight” (Luke 15:21). So, Matthew is preserving the culturally-correct “kingdom of heaven” while Mark and Luke are explaining that “heaven” is a reference to God. The actual words that came out of Jesus’ mouth were probably “Malchut shemayim” (mahl-KUT shuh-MAH-eem), which was a phrase common in rabbinic teaching in his day. Malchut, which we translate as “kingdom,” actually refers more to the actions of a king — his reign and authority, and anyone who is under his authority. Shemayim is Hebrew for “heavens.” A simple way of translating it would be “God’s reign,” or “how God reigns” or “those God reigns over.”

But what does it really mean?

Apparently, the discussion of Jesus’ day was focused on how and when God would establish his kingdom on earth. They were thinking of prophecies like those in Zechariah that say that one day,

The LORD will be king over the whole earth. On that day there will be one LORD, and his name the only name. (Zech. 14:9)

We may wonder why they felt that God wouldn’t be king from the beginning of creation, but they believed that as long as the world was filled with evil and other nations worshipped other gods, the people of the world refused to acknowledge him as its king. Especially in Jesus’ day this feeling was very strong. God’s people, Israel, were suffering at the hands of the Romans. They longed for the day that God would come to save his people and fully establish his reign over the earth.

The reason the ministry of Jesus focuses on the kingdom was because it was the role of the Messiah to establish God’s kingdom on earth. Messianic passages in the Old Testament focus on how God was going to anoint a king from the people of Israel to reign over the whole world, and that he would bring God’s kingdom to earth (see Is. 11, Ps. 2, 72, Dan. 2 and others). Because Jesus was the Messiah, he was describing his own mission as the Anointed King sent by God.

We can imagine that there would be much speculation in Jesus’ time about how God would establish his reign over the whole world. Obviously, they thought, when the Messiah came, he would establish God’s reign by conquering the enemies of Israel. They read many prophecies about the Messiah that were images of a mighty king who defeated his foes and then took the throne, for instance:

The kings of the earth take their stand and the rulers gather together against the LORD and against his Anointed One (Messiah, in Hebrew). … Then he rebukes them in his anger and terrifies them in his wrath, saying, I have installed my King on Zion, my holy hill. … You will rule them with an iron scepter; you will dash them to pieces like pottery. (Ps. 2:2,5-6, 9)

And, they read about the great and dreadful “day of the Lord” where he would come to judge the enemies of Israel, and they longed for that day. Messianic prophecy also talks about a “suffering servant” and a “Prince of Peace,” but the people of Jesus’ day expected that the Messiah would bring God’s judgment. This attitude was pervasive in Jesus’ time. The Essenes formed ascetic communities in the desert and called themselves the “sons of light,” waiting for the great war when God would destroy the “sons of darkness,” which was everyone except them. Even Jesus’ disciples were convinced that this was Jesus’ mission. They asked him “Lord, is it at this time You are restoring the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6). And, in the words of John the Baptist, we hear him warning his listeners that because the Messiah was here, the judgment of God was imminent:

Indeed the axe is already laid at the root of the trees; so every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.

His winnowing fork is in his hand to thoroughly clear his threshing floor, and to gather the wheat into his barn; but he will burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire. (Luke 3:9, 17).

Jesus’ Teaching About the Kingdom

Jesus teaching about the kingdom was to correct his people’s expectations of his messianic role, and even their understanding of God’s nature itself. Those around him wanted God to reign over the earth by destroying anyone who didn’t acknowledge him as king. Jesus, in contrast, says that God would establish his kingdom on earth, not by judgment, but by mercy to sinners, who would be reconciled with God through Jesus’ atoning death. This is the fundamental message of Jesus — the good news of the kingdom of God is that the Messiah had come, and was building his kingdom by bringing forgiveness to anyone who would repent, rather than bringing God’s judgment to the world.

If we see this as Jesus’ message, it gives insight on parables about the kingdom that are hard to understand otherwise. One seems to be directly intended to correct John the Baptist’s picture of the Messiah coming in judgment to establish God’s kingdom. We hear from John that “the axe is already laid at the root of the tree“, ready to chop it down because it doesn’t bear fruit. But Jesus tells the parable:

A man had a fig tree which had been planted in his vineyard; and he came looking for fruit on it and did not find any. And he said to the vineyard-keeper, ‘Behold, for three years I have come looking for fruit on this fig tree without finding any. Cut it down! Why does it even use up the ground?’ And he answered and said to him, ‘Let it alone, sir, for this year too, until I dig around it and put in fertilizer; and if it bears fruit next year, fine; but if not, cut it down. (Luke 13:6-9)

The point of this parable is to emphasize God’s mercy rather than his imminent judgment. Jesus seems to be speaking about the same tree that John was, only here the tree is given another chance, rather than being chopped down. Was John the Baptist wrong about Jesus? No, actually, because Jesus will eventually return in judgment, just as John said. When Jesus speaks about his return, he says that then he will come to separate the sheep from the goats, and judge the world. John was just premature in his timing, as were Jesus’ disciples. This is probably why John asks Jesus, “Are you the one who is to come, or should we look for another?” He was expecting Jesus to bring the judgment of God, but this was to come later.

The point of this parable is to emphasize God’s mercy rather than his imminent judgment. Jesus seems to be speaking about the same tree that John was, only here the tree is given another chance, rather than being chopped down. Was John the Baptist wrong about Jesus? No, actually, because Jesus will eventually return in judgment, just as John said. When Jesus speaks about his return, he says that then he will come to separate the sheep from the goats, and judge the world. John was just premature in his timing, as were Jesus’ disciples. This is probably why John asks Jesus, “Are you the one who is to come, or should we look for another?” He was expecting Jesus to bring the judgment of God, but this was to come later.

What are the implications of Jesus’ teaching?

Even though the main difference between Jesus’ picture of the kingdom of God and those around him was in the timing of the judgment, this difference had profound implications for the kind of kingdom it is, and the character of God himself.

The picture that most had about the kingdom is that it would be established through God’s judgment. It seems to be a logical answer to the problem of evil. In one sudden event, God would assert his power and vanquish his enemies, the “wicked” of the nations around them, and those of their own nation who were “sinners.” Only the righteous would be left to be God’s Kingdom. They assumed that they were the righteous that would survive the judgment, and that their enemies would not survive. This was good news to those who were the “righteous,” who were on God’s side, because they would have the victory.

Jesus utterly disagrees with this. He says that God’s kingdom had come to earth, but it would be a time of healing and forgiveness. He said that his kingdom would start out small like a mustard seed, but would grow as people would accept Christ and enthrone God as their King. In Jesus’ understanding, a person was brought into the kingdom of God when the person decided to accept God as his King, and it is something that happens in a person’s heart, not a political movement or visible display of God’s power. His idea was very close to that of other rabbis who said that when a person committed himself daily to love God with all of his heart, soul, mind and strength, that he had “received upon himself the kingdom of heaven.” This kingdom would be invisible, like leaven that some how works its way through bread to make it rise. We can hear this in this conversation:

Now having been questioned by the Pharisees as to when the kingdom of God was coming, He answered them and said, “The kingdom of God is not coming with signs to be observed; nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or, ‘There it is!’ For behold, the kingdom of God is in your midst.” (Luke 17:20 – 21)

Jesus is saying through this that he was the Messiah, and he truly had brought God’s kingdom to earth. But it would be a very different kind of kingdom because it would grow through forgiveness of sin rather than judgment. It was good news to the sinners who knew that if God came in judgment, they would be the ones to be judged!

Also, because the kingdom was growing slowly by God’s mercy toward sinners, it would be like like wheat that grows up among “tares,” or weeds (Matt 13:24-30), representing evil. When the tares were found growing in the field, instead of pulling them out, the farmer waited until the end. The farmer was merciful, preferring to leave the weeds alone in his desire not to harm the wheat. Once again, this contrasts with John’s saying that the Messiah would come to winnow — meaning to separate the wheat from the chaff, or good from evil, for destruction. Again, Jesus is saying that God’s kingdom had truly come to the earth, but evil would not be ended, so it would not be a kind of utopia. Rather, it would grow in the midst of evil because of God’s mercy, so that there was still hope for the enemies if they chose to repent and enter.

If we have this understanding, many of Jesus’ sayings make more sense. His kingdom is made up of the poor in spirit, those who know they are guilty of sin, who come to God for forgiveness. The tax collectors and prostitutes were the first to enter Jesus’ kingdom of mercy, and the last were the outwardly religious who really were hoping for God to judge their enemies. The merciful, who do not want to see God’s judgment come on others, are shown mercy themselves. One day, the kingdom would come in power when Jesus returns to judge, but he would wait as long as possible to allow as many to enter as can.

Jesus’ picture of the kingdom of God gives us a profoundly different understanding of God’s character. It shows that God is, at his very heart, merciful and wanting no one to perish. He teaches us to love our enemies, because he himself is merciful toward his enemies, giving them time to change their ways. It is easy to see what our response must be to Jesus’ message. We must examine ourselves, know that no one is righteous in the eyes of God, and repent and receive God as our King. Only because the Messianic King came to die to establish his Kingdom, rather than to kill his enemies, can we, his former enemies become members of his Kingdom and children of his Father.

~~~~

To explore this topic more, see chapter 12, “Jesus and the Torah” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 163-179.

To explore this topic more, see chapter 12, “Jesus and the Torah” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 163-179.

Photos: Johannes Plenio on Unsplash, Annie Spratt on Unsplash, David Köhler on Unsplash, Johannes Plenio on Unsplash

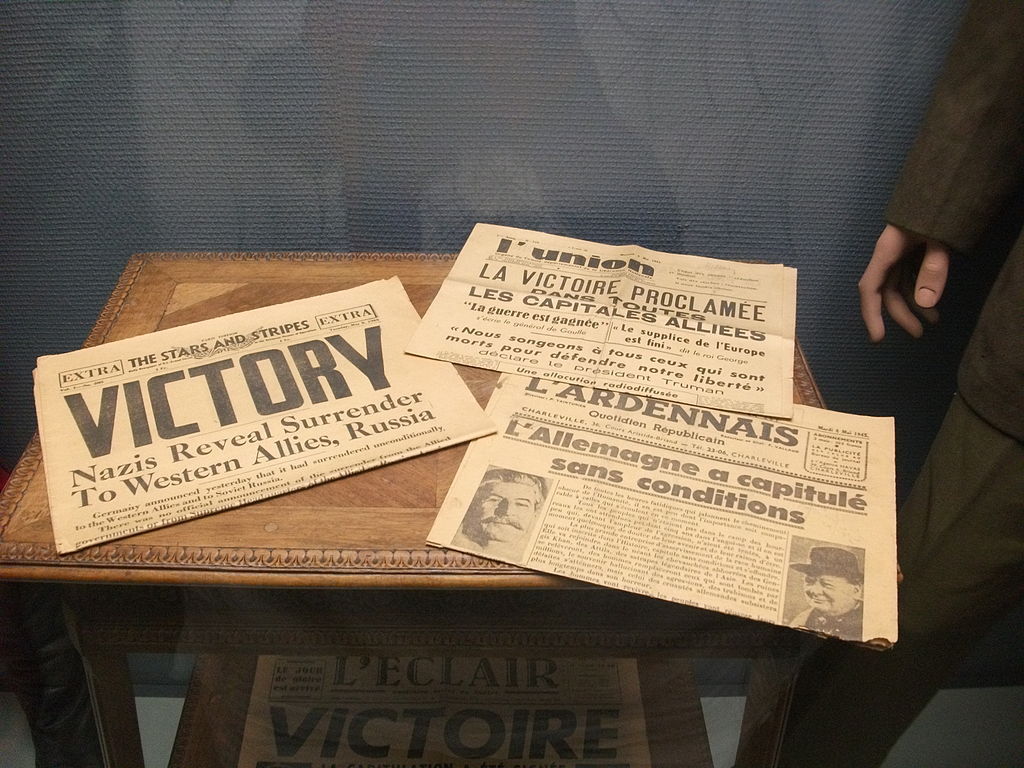

Interestingly, the Hebrew word besorah, which we translate to “good news,” has exactly that connotation. It is news of national importance: a victory in war, or the rise of a powerful new king. The word was used in relation to the end of the exile (Isaiah 52:7) and the coming of the messianic King (Isaiah 60:1). Often it is news that means enormous life change for the hearer.

Interestingly, the Hebrew word besorah, which we translate to “good news,” has exactly that connotation. It is news of national importance: a victory in war, or the rise of a powerful new king. The word was used in relation to the end of the exile (Isaiah 52:7) and the coming of the messianic King (Isaiah 60:1). Often it is news that means enormous life change for the hearer.