by Lois Tverberg

The Bible is an ancient book, and the honest reader will admit that many passages are hard to understand. Sometimes Jesus’ words can be the most difficult, and prone to speculation and even misinterpretation. A case in point is Jesus’ saying from the Sermon on the Mount:

The light of the body is the eye: if therefore thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light. But if thine eye be evil, thy whole body shall be full of darkness. (Matt 6:22-23, KJV)

Every Bible translation attempts to explain this obscure saying by clarifying the phrases about one’s “eye.” Various translations use terms like clear eye/bad eye (NASB), healthy eye/unhealthy eye (NRSV), eyes are good/eyes are bad (NIV). None of these adequately explain Jesus’ idea to modern readers.

This opens the door for all sorts of interpretations. John Wesley, who lived in the 1700’s, interpreted the “single eye” as being utterly devoted to pleasing God, and the “evil eye” as having our interests devoted anywhere else, to distract us from God.1 While his interpretation is well within traditional understanding, others come to different conclusions.

One author sees Jesus as saying that we should deeply appreciate our physical senses and ability to see.2 In contrast, a well-known New Age teacher believes that Jesus was speaking of the “third eye chakra” or inner eye of enlightenment. When humans were first created perfect, she says, they were enlightened by this third eye, but after the fall, it is now only reached through meditation.3

One author sees Jesus as saying that we should deeply appreciate our physical senses and ability to see.2 In contrast, a well-known New Age teacher believes that Jesus was speaking of the “third eye chakra” or inner eye of enlightenment. When humans were first created perfect, she says, they were enlightened by this third eye, but after the fall, it is now only reached through meditation.3

While Wesley’s interpretation agrees more with the Scriptures as a whole, we still have to admit that he was guessing at the meaning of the strange phrase, without knowing its cultural context. Christians have the frustrating task of defending one interpretation over another, when are all based in subjective interpretation.

A Cultural Perspective — A Good Eye

A better way to discern what Jesus was saying is to look at his words in the context of his first century culture. All languages have idioms — figures of speech that don’t make sense literally, like “raining cats and dogs,” “beating around the bush” or “pulling someone’s leg.” We should expect that Jesus’ sayings may contain cultural idioms that we don’t understand.

Indeed, in the Greek gospels we find many idiomatic phrases that sound awkward or don’t make sense in Greek, even though they make perfect sense in Hebrew.4 By looking at the Semitic idioms in the Old Testament and in Jewish literature of Jesus’ day, we can get a much clearer understanding of Jesus’ teaching, and have more confidence about Jesus’ message.

One interesting hypothesis is that Jesus may have been using a Hebraic idiom that contrasts a “good eye,” ayin tovah, and a “bad eye” or “evil eye” ayin rah. The Hebraic understanding of “seeing” goes beyond taking in visual information in the eyes — it refers to one’s outlook on life and attitude toward others. It can even mean to respond according to a need that is seen. For example, the phrase Jehovah Jireh is often translated to “God will provide,” but it means, literally, “God will see,” meaning that when God sees our need, he will respond.

An idiom that emerged out of this idea is that a person with a “good eye” is generous — he sees the needs of others and wants to help them. In contrast, one with an “bad eye” or “evil eye” is blind to the needs of others and is greedy and focused on his own self-gain. We find these idioms in Proverbs:

Prov. 22:9 He who is generous (literally, has a good eye) will be blessed, for he gives some of his food to the poor.

Prov. 23:6 Do not eat the food of a stingy man (literally, an evil eye), do not crave his delicacies; for he is the kind of man who is always thinking about the cost.

Prov. 28:22 A man with a bad eye hastens after wealth and does not know that want will come upon him.

In fact, Jesus uses the idiom of “evil eye” for greed elsewhere in the gospels. At the end of the parable of the landowner who pays all the laborers the same, the landowner says to the workers, ‘Is it not lawful for me to do what I wish with what is my own? Or is your eye evil because I am generous?’ (Matt. 20:15). The Greek phrase there, opthalmous sou ponerous is identical to that in Matt 6:23, the passage that we are examining.

Interestingly, if this is our interpretation of the passage in Matthew 6, Jesus’ saying suddenly fits into the larger context of this passage. Here is the longer context of that saying:

But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys, and where thieves do not break in or steal; for where your treasure is, there your heart will be also. The eye is the lamp of the body; so then if your eye is clear, your whole body will be full of light. But if your eye is bad, your whole body will be full of darkness. If then the light that is in you is darkness, how great is the darkness! No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth. (Matt 6:21-24, NASB)

Right before the “eye” analogy, Jesus tells his listeners to “store up treasures in heaven,” which is an idiom for giving money to the poor.5 Afterward he says, “No one can serve two masters … you cannot serve God and wealth.” (Matt 6:24). If Jesus is using the idioms “good eye” and “evil eye” to mean generosity and greed with money, the teaching about ones “eye” now fits perfectly into a longer saying about how to use money in a way that honors God.

Having a Single Eye

Any hypothesis needs to be re-evaluated in light of new evidence, and one scholar points out that the Greek wording of the passage does not say “good,” kalos, but “single, simple,” haplous. The idea of “singleness of eye” as a virtue is also found in other Greek documents from Jesus’ time, and “singleness,” haplotes, as a virtue is used several other places in the New Testament.6 This can also give us insight on Jesus’ meaning in this passage. One document reads:

Any hypothesis needs to be re-evaluated in light of new evidence, and one scholar points out that the Greek wording of the passage does not say “good,” kalos, but “single, simple,” haplous. The idea of “singleness of eye” as a virtue is also found in other Greek documents from Jesus’ time, and “singleness,” haplotes, as a virtue is used several other places in the New Testament.6 This can also give us insight on Jesus’ meaning in this passage. One document reads:

“I never slandered anyone, nor did I censure the life of any man, walking as I did in singleness of eye” (3:4)… “And now hearken to me, my children, and walk in singleness of heart… The single [minded] man covets not gold… There is no envy in his thoughts, nor [does he] worry with insatiable desire in his mind. For he walks in singleness, and beholds all things in uprightness of heart… Keep, therefore, my children, the law of God, and attain singleness…7

Here the idea of “singleness of eye” means sincerity, simplicity, and a freedom from envy for money. It is the opposite of having a “double heart” as in Psalm 12:2: “They speak falsehood to one another; with flattering lips and with a double heart they speak.” A person with a “single eye” is one of integrity who does not have a secret agenda of self-advancement. Along with sincerity of spirit, he also has an integrity toward money that keeps him from covetousness and greed. Another passage from about the same time also gives insight:

The good man has not an eye of darkness that cannot see; for he shows mercy to all men, sinners though they may be, and though they may plot his ruin … His good mind will not let him speak with two tongues, one of blessing and one of cursing, one of insult and one of compliment, one of sorrow and one of joy, one of hypocrisy and one of truth, one of poverty and one of wealth; but it has a single disposition only, simple and pure, that says the same thing to everyone.8

Interestingly this passage talks about a man’s “eye” in terms of his caring for the needs of others, and contrasts an “eye of darkness” to a disposition of “singleness.” The contrast is between pretending to care about others with an inward attitude of self-advancement, compared to having a genuine concern for others, without hidden motives.9

Reading Jesus’ Words Again

In light of these idioms, here is my dynamic translation of Matthew 6:21-24, incorporating the idiomatic language he appears to be using:

So give generously to the poor and invest your energy and resources in eternal things, because when you do, your priorities and outlook will change. Your outlook toward others shows your true inner self. If you have a sincere, un-envious heart that wants to help others, your whole personality will shine because of it. But if you are blind to the needs of others and are self-centered and greedy, your soul will be dark indeed. You cannot be a slave to your own greed and try to serve God — you have to choose.

In this entire passage, Jesus seems to be equating how we use our money with our basic attitude on life, and says that our generosity is the true measure of us as persons. When you get right down to it, if money rules us, God doesn’t. It is one of Jesus’ many teachings on money and what our attitude should be about it. In our materialistic culture, his words hit home.

In this entire passage, Jesus seems to be equating how we use our money with our basic attitude on life, and says that our generosity is the true measure of us as persons. When you get right down to it, if money rules us, God doesn’t. It is one of Jesus’ many teachings on money and what our attitude should be about it. In our materialistic culture, his words hit home.

This cultural study of the phrase “single eye” and “bad eye” can shed a lot of light on Jesus’ teachings. It should make us eager to learn more when we see that the strange phrases that we sometimes find in the Bible had parallels in other ancient texts that can help explain them.

Our interpretation of Jesus’ words can be much more solid, so that we have confidence that we are hearing Jesus’ ideas and not just our own. Otherwise, our interpretations are based on speculation from personal experience that can lead us down all sorts of strange paths, as some have gone on in understanding Jesus’ words about “the single eye.”

As important as it is to read the Bible accurately, it is even more important that once we understand Jesus’ teaching, we take it to heart and change our lives because of it. Are we people of sincerity and integrity? Do we use our money to help others, and find ways to meet their needs? Or, in our hearts, is our own comfort and wealth our number one priority? Jesus is saying that we can’t be his followers if we are greedy and self-centered. We need to choose who we will serve — God or ourselves.

~~~~

1 John Wesley, On A Single Eye – Sermon available at this link.

2 Herbert Lockyer, All the Parables of the Bible (Zondervan, 1988), 149-50.

3 Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Lost Teachings of Jesus (Summit University Press, 1986), 281.

4 This is the subject of the book Understanding the Difficult Words of Jesus: New Insights from a Hebraic Perspective by Bivin & Blizzard, 1994, Destiny Image Publishers.

5 See Matthew 19:2, Mark 10:21, Luke 18:22 and “The Best Long-Term Investment: Making Loans to God” at www.jerusalemperspective.com.

6 See “If Your Eye Be Single” by Steven Notley at www.jerusalemperspective.com.

7 Testament of Issachar, 3:4, 4:1-2, 5-6; 5:1 (quoted in the article Notley article above). The Testament of Issachar is of the body of literature called the “pseudepigrapha” – Jewish writings from 200 B.C. to 200 A.D. that are not canonical, but show the cultural expressions and religious understandings of that time.

8 Testament of Benjamin 4:2-3 (quoted in the article Notley article above). Also of the pseudepigrapha.

9 James speaks about the wrongness of having a “double mind” in vs. 1:8 and 4:8 and the importance of sincerity of the tongue in 3:9-12. He uses a very similar phrase as in this passage in 3:9 — having a tongue of “blessing and cursing” — which should not be the case. A related word to haplous used in the gospels, haplotes, meaning “singleness,” is used often in the New Testament for sincerity, especially in exhortations to have a “single heart” (See 2 Cor. 1:12, 11:3, Eph. 6:5, Col. 3:22).

It should be noted that Hebrew does not use “single eye” as an idiom for sincerity. More likely, since Matthew’s Greek readers wouldn’t have understood “good eye” any more than we do, he translated this phrase by using haplous, since Greeks used it to mean generosity. Matthew would have been using a Greek idiom to translate a Hebrew idiom. This may also be true for the Testament of Issachar, which is preserved in Greek, even though it was originally written in Hebrew.

Photos: Normann Copenhagen; Vladimer Shioshvili; Internet Archive Book Images [No restrictions]

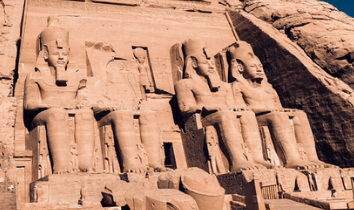

God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers.

God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers. When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4

When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4

In a later source, the Babylonian Talmud, it says “He who judges his neighbor favorably will be judged favorably by God” (Shabbat 127a). It is interesting to see how reminiscent this is of Jesus’ saying, “with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” To “judge in favorable terms” was considered as important as visiting the sick, devotion in prayer, or teaching the Scriptures to your children!

In a later source, the Babylonian Talmud, it says “He who judges his neighbor favorably will be judged favorably by God” (Shabbat 127a). It is interesting to see how reminiscent this is of Jesus’ saying, “with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” To “judge in favorable terms” was considered as important as visiting the sick, devotion in prayer, or teaching the Scriptures to your children! What would happen if each group stopped assigning negative motivations to the other group? What if the “hymns only” group started saying, “Maybe the younger members of our church think that they can bring new meaning to the service by putting it in their own style…” What if the “rock band” enthusiasts started saying, “Maybe the older members find more meaning in what’s familiar rather than in what sounds strange to them…”

What would happen if each group stopped assigning negative motivations to the other group? What if the “hymns only” group started saying, “Maybe the younger members of our church think that they can bring new meaning to the service by putting it in their own style…” What if the “rock band” enthusiasts started saying, “Maybe the older members find more meaning in what’s familiar rather than in what sounds strange to them…” While we can discern sin in practice, only God knows the motive of the heart. We need to leave final judgment up to him. To judge another is to presume to have both the knowledge and authority of God himself. So when we are in a situation where we are tempted to condemn someone, we need to step back, hand the situation over to the Lord, and remind ourselves that it is his job to render judgement, not ours. As we read in James 4:12, “There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the One who is able to save and to destroy; but who are you who judge your neighbor?”

While we can discern sin in practice, only God knows the motive of the heart. We need to leave final judgment up to him. To judge another is to presume to have both the knowledge and authority of God himself. So when we are in a situation where we are tempted to condemn someone, we need to step back, hand the situation over to the Lord, and remind ourselves that it is his job to render judgement, not ours. As we read in James 4:12, “There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the One who is able to save and to destroy; but who are you who judge your neighbor?”