by Lois Tverberg

For the foolishness of God is wiser than man’s wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than man’s strength. (1 Corinthians 1:25)

Many have seen the musical Fiddler on the Roof and recall that the father, Tevya, had an amusing habit of chewing over every issue with several rounds of, “On the one hand… but on the other hand…!” This habit of looking at things in terms of two contrasting viewpoints is distinctly Jewish, and a part of their Eastern-thinking culture.

Often the two points of view are left unresolved and simply accepted as a paradox. Western-thinking Christians, however, often struggle to find systematic treatment of every issue, and are frustrated by how the Bible sometimes seems to be contradictory. Rather than trying to make the Bible more “logical” by Western standards, we’ll have a deeper understanding of it if we learn to read it with “both hands,” as Jesus, Paul and Jews over the ages have done.1

Paradoxes throughout Bible

If you think about it, many of the most important truths of the Bible are paradoxical. God is both omniscient, but yet he is present at certain times in a unique way, like at the burning bush. Jesus is both fully human and fully God. God is loving and in control, and yet he allows tragedy and injustice to take place.

Jesus’ words also often come in paradoxes. He says that “if anyone wants to be first, he must be the very last” (Mk 9:35) and that “he who loves his life will lose it, while he who hates his life will keep it for eternity” (Jn 12:25).

Jesus’ words also often come in paradoxes. He says that “if anyone wants to be first, he must be the very last” (Mk 9:35) and that “he who loves his life will lose it, while he who hates his life will keep it for eternity” (Jn 12:25).

When Western-thinkers find a paradox in the Bible, they often are tempted to resolve the conflict by rejecting one side for the other. For instance, the question of whether humans have free will or whether our actions are predestined has divided Christians for centuries.

Some reject free will entirely, as if humans are only puppets in God’s hands. Others reject the idea that God is in control, imagining that God is wringing his hands in heaven, hoping that in the end everything will come out OK. Many churches have divided over these issues.

In contrast, the rabbinic answer was simply, “God foresees everything, yet man has free will.”2 Their observation was that passages in Scripture actually support both points of view! Pharaoh hardened his own heart, and yet God hardened his heart (Ex 7:3, 13; 8:15). God foresaw that it would take 400 years for the Canaanites to become so evil that he would evict them from their land (Gen 16:15). But he also offered the choice to the Israelites to take on his covenant or not (Dt 30:19).

Amazingly, the rabbis simply embrace the two ideas in tension with each other rather than needing to seek resolution. By doing so, they are actually being true to the text by not ignoring passages that don’t fit their theology. They see that God alone can understand some things.

Balancing Mercy and Justice in a Parable

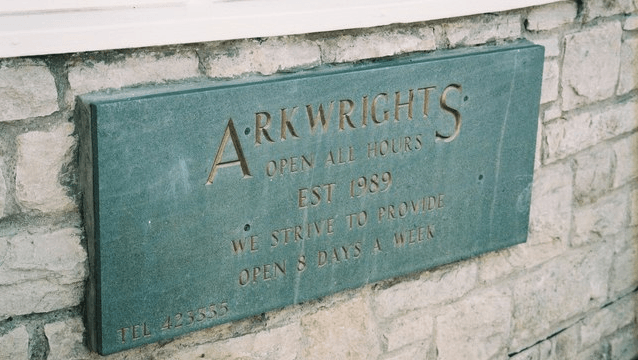

One Jewish way of comprehending contrasting truths is to put them into a parable. For instance, God describes himself as both slow to anger and forgiving, yet he says he will punish the wicked to the third and fourth generation (Ex. 34:6-7). Some have concluded that the God of the Old Testament was full of judgment, but is now full of love, since Christ died for our sins. If we read more closely, however, we find that neither is the case.

God forgave the Israelites for worshipping the golden calf, but then forbade Moses, his greatest prophet, from entering the promised land because he struck the rock. Likewise, Jesus spoke about the coming judgment more than anyone else in the New Testament, yet he told the woman caught in adultery that her sins had been forgiven. He said, “Woe to you, blind guides!” (Matt 23:16) but later said, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Lk 23:34).

How can God be both just and merciful? The rabbis told the following parable:

“This may be compared to a king who had a craftsman make for him an extremely delicate, precious goblet. The king said, ‘If I pour hot liquid into it, it will burst, if I pour ice cold liquid into it, it will crack!’ What did the King do? He mixed the hot and the cold together and poured it into it, and it did not crack.” Even so did the Holy One, blessed be He, say: “If I create the world on the basis of the attribute of mercy alone, it will be overwhelmed with sin; but if I create it on the basis of the attribute of justice alone, how could the world endure? I will therefore create it with both the attributes of mercy and justice, and may it endure!” (Genesis Rabbah 12:15, adapted.3)

This parable doesn’t use detailed theological terms to explain why God is merciful sometimes and why he chooses to judge at other times — it merely points out that both are needed in order for God to reign over creation while allowing it to survive. Parables like this show the difference between Jewish and Christian thought, because they attempt to comprehend by describing through story, without the assumption that humans can explain God’s mysterious ways.

Besides being a wise approach to looking at the nature of God, this parable also illustrates the “both hands” approach of Judaism as to how we should live. It points out that a blend of mercy and judgment is often what we need in our lives.

Besides being a wise approach to looking at the nature of God, this parable also illustrates the “both hands” approach of Judaism as to how we should live. It points out that a blend of mercy and judgment is often what we need in our lives.

Parents struggle with the balance of enforcing rules along with showing grace to their children — not being too strict, yet not letting their kids run wild. Or, when our spouses do something that hurts us, should we forgive them and let it slide, or, should we bring our hurt and anger to their attention?

Christians tend to think there must be only one right way to act in these situations — either to never let sin go unpunished, or to always be forgiving. In reality, we need to have both discernment and balance. Even God walks the difficult line between mercy and judgment! We can turn to him for guidance because he knows our struggles beyond what we could ever imagine.

“Weighing” the Laws Against Each Other

Another way Jewish thought seeks balance is in its approach to the law. Christians have traditionally understood all of the commandments to be of equal importance, but in the time of Jesus, the rabbis “weighed” the laws so that in a situation where two laws conflict with each other, a person knew which one to follow.

For instance, the command to circumcise on the eight day took precedence over the Sabbath (Jn 7:22). This came out of an effort to live by God’s laws in all situations, rather than arbitrarily ignoring some and doing others. They would describe the laws in terms of being “light,” kal, and “heavy,” hamur. Certain principles derived from the Bible were used to organize laws relative to each other, and the focus of many rabbinic debates was how to prioritize them.

One rabbinic principle is Pikuach Nephesh (pi-KOO-akh NEH-fesh), which is the preservation of life.4 The rabbis saw that Leviticus 19:16 says, “Do not stand by while your brother’s blood is shed” — meaning if someone’s life is in danger, you must intervene. The Torah also says the law was given in order to bring life, (Ex. 30:15-16), so they concluded that all laws (except a few) should be set aside to save a human life.5

Because of this, Jewish doctors and nurses go to work on the Sabbath, because they may potentially save a life, and if a person is ill, he or she is supposed to eat on Yom Kippur, the day when eating and drinking are strictly forbidden. Even the possibility of saving a life is enough to put this principle into effect. The rabbis would disagree with the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ policy of refusing blood transfusions in a medical emergency, because of the prohibition against drinking blood in Genesis 9:4. The weightier law is to save life!

An interesting example shows the contrasts in approach to the law. Imagine you lived in Europe during World War II and were hiding Jews in your home, and a Nazi came demanding to know where they were. Should you lie or tell the truth? According to the principle of Pikuach Nephesh, you should lie to save their lives. There is also biblical precedent in Exodus, when the midwives lied to Pharaoh rather than to kill the Israelite boys, and God rewarded them (Ex. 1:19-21).

An interesting example shows the contrasts in approach to the law. Imagine you lived in Europe during World War II and were hiding Jews in your home, and a Nazi came demanding to know where they were. Should you lie or tell the truth? According to the principle of Pikuach Nephesh, you should lie to save their lives. There is also biblical precedent in Exodus, when the midwives lied to Pharaoh rather than to kill the Israelite boys, and God rewarded them (Ex. 1:19-21).

Surprisingly, Christians have sometimes come to the opposite conclusion. The theologian St. Augustine actually said, “Since, then, eternal life is lost by lying, a lie may never be told for the preservation of the temporal life of another.”6 He would conclude that a person must answer the Nazi truthfully no matter what. It appears that in his thinking, all rules are absolute. This logic forces one to conclude that law to intervene to save life (Lev. 19:16) and the law against lying (Lev. 19:11) are irreconcilable.

Jesus Weighed the Laws Too

Jesus used the principle of Pikuach Nephesh when he was arguing what may be done on the Sabbath in Luke 6, when he said, “I ask you, which is lawful on the Sabbath: to do good or to do evil, to save life or to destroy it?” Both activities under debate in that chapter were an effort to preserve life — the plucking of grain to satisfy hunger, and the healing of the man’s hand.

The point was not that Jesus was throwing aside the Sabbath as unimportant, because keeping the Sabbath was extremely important throughout the Torah. It was the “sign of the covenant” which was symbolic of a Jew’s commitment to all of the Sinai covenant (Ex. 31:13). Jesus was saying that as important as it is to honor the Sabbath, human life is even more important. He concluded, “The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27).

How then do we prioritize our obedience? The idea of “weighting” the laws of the Torah was likely the rationale for the question, “Of all the commands, which is greatest?” (Mark 12:28-30). The lawyer was asking, “What is our ultimate priority as we try to obey God?” Jesus’ answer, of course, was to quote the commands that said that we should love God wholeheartedly, and love our neighbor. Everything we do should be towards that end.

Jesus illustrates his point with the parable of the Good Samaritan, which points out the wrong priorities of the two characters who wanted to go worship at the Temple rather than helping the dying man. Of course, the right thing to do in this case was to attend the needs of the wounded man, showing him the love of God.

Jesus illustrates his point with the parable of the Good Samaritan, which points out the wrong priorities of the two characters who wanted to go worship at the Temple rather than helping the dying man. Of course, the right thing to do in this case was to attend the needs of the wounded man, showing him the love of God.

Does this mean we can ignore God’s standards altogether? Not at all! Reading Matthew 5, one wonders if Jesus was accused of this, and he needed to defend his approach. There he emphatically said he came not to undermine the law, but to explain it and live by it faithfully.7

He then said that anyone who breaks one of the least of these commandments will be called least in the kingdom of heaven. He was emphatically stating that we should aim to be obedient in all ways, but that we should always aim to love, and that sets our priorities for how we should obey. As Tevya would phrase it, on the one hand, be obedient, but on the other hand, choose to love!

This is a wise word for how to discern what to do when two commands conflict with each other. If you must choose one over the other, choose the one that shows the most love. If you don’t do yard work on Sunday (or Saturday), but your elderly mother really needs her lawn mowed and it’s the only day you can help, you should do it then. Or, if your family celebrates holidays with a tradition that you don’t embrace, seek to do what is loving rather than dividing the family over it. Choose the most loving path. Jesus himself would probably do the same thing in your situation, and indeed, he is using you to do it.

~~~~

To explore this topic more, see chapter 10, “Thinking with Both Hands” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 130-41.

To explore this topic more, see chapter 10, “Thinking with Both Hands” in Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2012, p 130-41.

1 Two other excellent references for further reading are: Our Father Abraham: Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, by Marvin Wilson (Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI, 1989) pp 150-153; and The Gospel According to Moses: What My Jewish Friends Taught Me About Jesus, by Athol Dickson (Brazos Press, Grand Rapids, MI, 2003), pp 63-80.

2 Rabbi Akiva, (who lived between about 50-135 AD) Mishnah, Avot 3:16.

3 See “Jewish Concepts: Loving-kindness” from jewishvirtuallibrary.org for more.

4 B. Talmud, Shabbat 132a.

5 There were three laws that were so weighty that they could not be broken to save life, and these were idolatry, sexual immorality, and murder. These also were the three laws given to the Gentiles who were entering the early church in Acts 15, according to David Bivin. See New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus: Insights from His Jewish Context, pp. 141-144.

6 As quoted by J. Telushkin, The Book of Jewish Values, (Bell Tower, New York, 2000), p. 100.

7 See the article “What Does It Mean to ‘Fulfill the Law.’“

Photos: Portland Center Stage [Flikr], Sébastien Bourdon [Public domain], , Balthasar van Cortbemde [Public domain]

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).

According to Acts, the reason Christians have not been required to observe the Torah was not because it has ended, but because we are Gentiles (at least most of us).