by Lois Tverberg

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Matthew 5:3

Who are those who are the poor in spirit, and how do they possess the kingdom of heaven? It helps a lot to know the idioms of Jesus’ time and his references to the scriptures. The phrase “poor in spirit” is an allusion to Isaiah 66:2:

This is the one I esteem: he who is humble (poor, ani) and contrite in spirit, and trembles at my word. Isaiah 66:2

The word “poor” is ani in Hebrew, and is also often translated “afflicted,” and often used to refer to groups of people like widows and orphans who were dependent on charity to survive. A person who is “poor in spirit” sees himself as needy and helpless without God, and yearns desperately for God’s presence in his life. Like a recovering addict, he can only survive each day by leaning on God. The opposite type of person is someone who is “great of spirit” who is bold and self-reliant, who has no need of anyone’s help, especially not God’s. He is one who feels that he is “the captain of his fate, the master of his soul.”

The word “poor” is ani in Hebrew, and is also often translated “afflicted,” and often used to refer to groups of people like widows and orphans who were dependent on charity to survive. A person who is “poor in spirit” sees himself as needy and helpless without God, and yearns desperately for God’s presence in his life. Like a recovering addict, he can only survive each day by leaning on God. The opposite type of person is someone who is “great of spirit” who is bold and self-reliant, who has no need of anyone’s help, especially not God’s. He is one who feels that he is “the captain of his fate, the master of his soul.”

The overall picture of Isaiah 66:2 is that God looks with favor on those who know they are inadequate to run their own lives, but show reverence for God, and are sorry for their sins. When we bring this picture of a person who is “poor in spirit” into Jesus’ saying in the beatitudes, it fits with the Kingdom of Heaven as we understand it hebraically.

The “kingdom of Heaven” is the same thing as the “kingdom of God” — it is not being used to refer to heaven after we die. Rather, it describes God’s reign over the lives of people here on earth. Not all people are in God’s kingdom, but a person enters the kingdom by enthroning God as his king, committing himself to doing God’s will. (1)

So we see now that a person who is poor in spirit is one who sees his need for God’s reign over his life, and submits to his rules. God’s kingdom consists of exactly this kind of people — those who are humble and needy enough to yearn after him.

(1) For a more complete understanding of the Kingdom of Heaven, see the following articles: What is the Kingdom of Heaven? and The Kingdom of Heaven is Good News

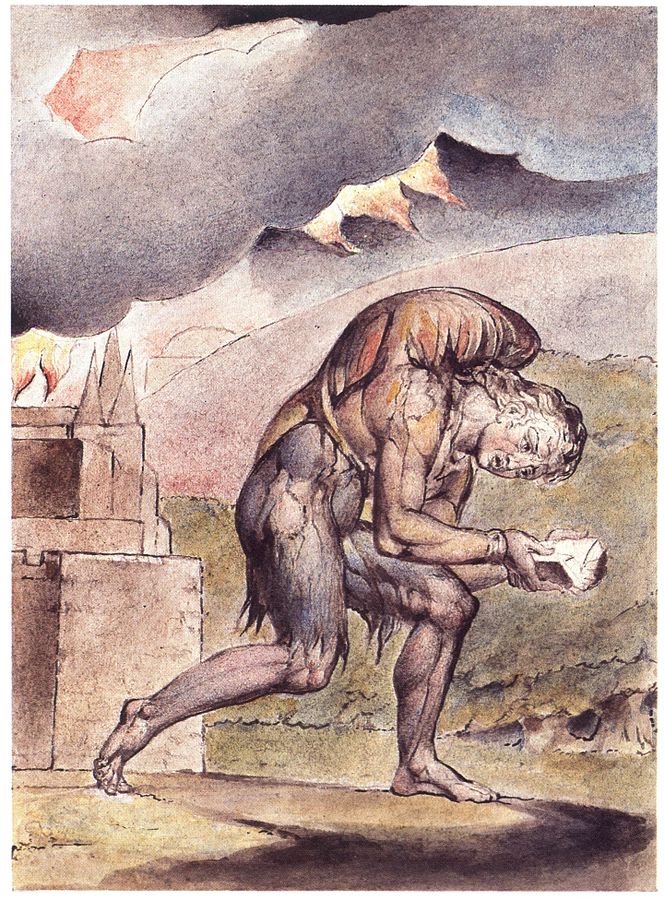

Photo: William Blake

On the other hand, in Israel, murder always called for capital punishment rather than monetary fines, as in other cultures. Other nations also demanded brutal punishments for people of lower classes for minor offenses against the rich. Israel, in contrast, treated all criminals alike. Their punishment was far more humane, usually demanding restitution to the victim rather than bodily damage to the offender.

On the other hand, in Israel, murder always called for capital punishment rather than monetary fines, as in other cultures. Other nations also demanded brutal punishments for people of lower classes for minor offenses against the rich. Israel, in contrast, treated all criminals alike. Their punishment was far more humane, usually demanding restitution to the victim rather than bodily damage to the offender.