by Lois Tverberg

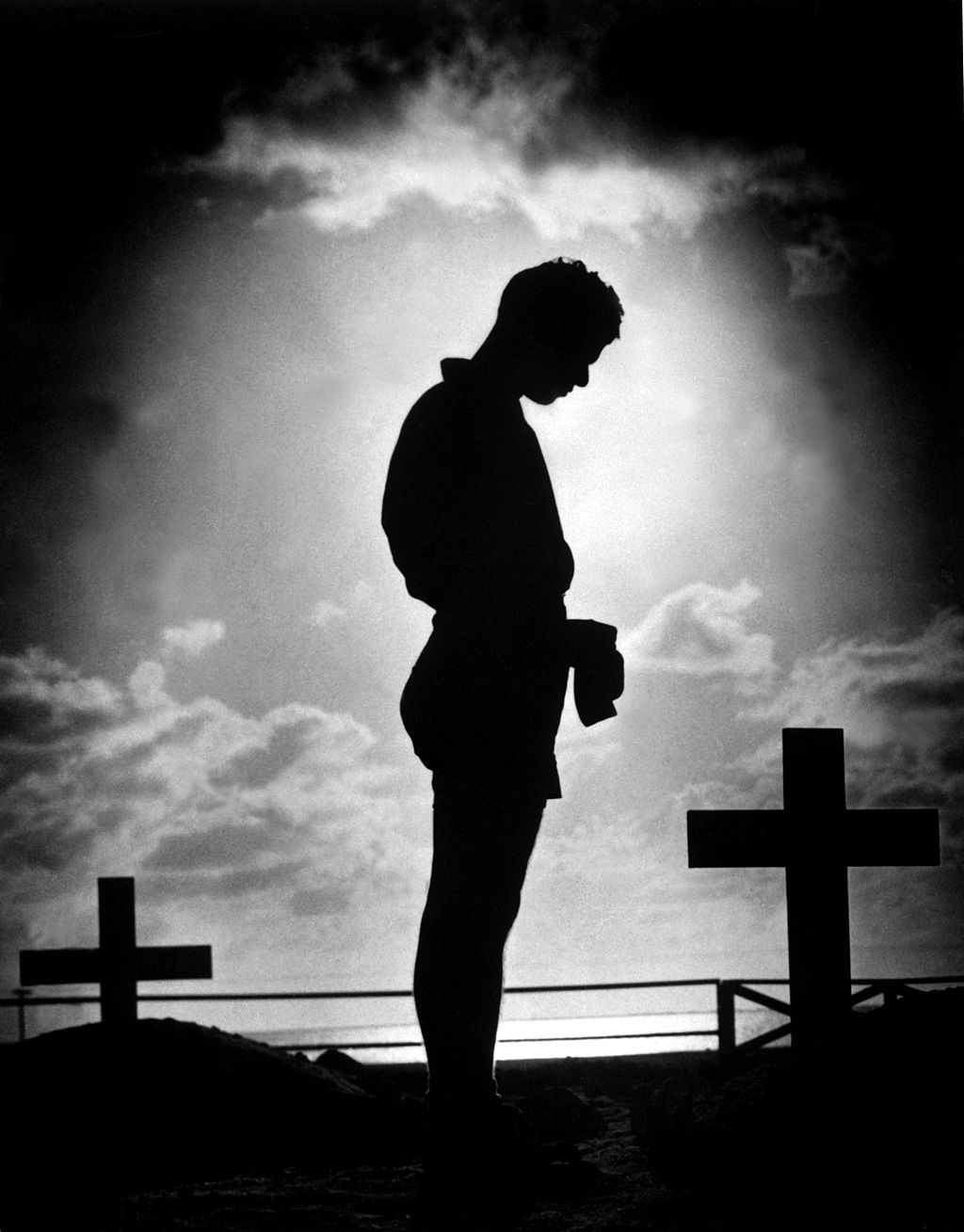

And do not lead us into temptation, but deliver us from evil … (NASB) or – the evil one. (NIV) Matthew 6:13

This is a line from the Lord’s prayer that is confusing to many. Some translations say “deliver us from evil,” others say “deliver us from the evil one.” Does it mean evil in general, or Satan in particular? And why would we ask God not to tempt us? Since Jesus told us to pray this way, certainly it would benefit us to clarify his words.

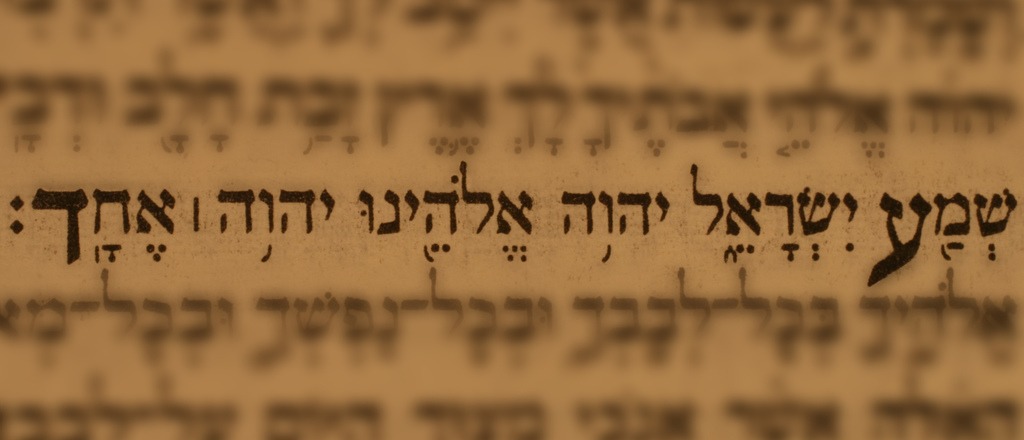

A key to understanding is to look at how the phrase “deliver us from evil” is used in both the Bible and in other Jewish prayers. In Psalm 121 it says,

The LORD is your keeper; The LORD is your shade on your right hand. The sun will not smite you by day, nor the moon by night. The LORD will protect you from all evil; He will keep your soul. (Psalm 121:5-7)

Here, protection from evil means protection from harm in general. And indeed the Hebrew word “ra” (evil or bad) is broad, and can include injury and misfortune as well as moral evil. In Psalm 141, the prayer asks for protection against doing evil:

Set a guard over my mouth, O LORD; keep watch over the door of my lips. Let not my heart be drawn to what is evil, to take part in wicked deeds with men who are evildoers; let me not eat of their delicacies. (Psalm 141:3-4)

Other Jewish prayers include the words “protect us from evil,” and can give us some insight. In the Talmud* a prayer expands on the meanings of the Hebrew word ra, “evil,” by saying, “Deliver me…from a bad person, a bad companion, a bad injury, an evil inclination, and from Satan, the destroyer.” Four times the word for “evil” is used, and here it is a petition to ask God to deliver the person from harm, but also from sin and the company of those who would cause a person to sin as well, and even Satan.

What about the line before “keep us from evil,” which is “lead us not into temptation”? This phrase is a Jewish way of saying “Do not let us succumb to the temptation of sin.” It is a parallelism to the next line, meaning, “Do not let us succumb to the evil inside us, do not let us sin.” Once again it is asking God to protect us from the evil we ourselves can do.

We would not go wrong in understanding these two lines as meaning, “Oh Lord, help us to keep doing your will, and don’t let us be led away from your path. Keep us from the evil within us and from spiritual forces of evil, and keep us from all harm and calamity too.” It is an all-encompassing plea for God to protect us from what is outside us, but what is inside as well.

~~~~

To explore this topic more, see chapter 5, “Get Yourself Some Haverim” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 66-77.

To explore this topic more, see chapter 5, “Get Yourself Some Haverim” in Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, Zondervan, 2009, p. 66-77.

*The Talmud is a compendium of Jewish commentary written about 300 AD, containing oral traditions from Jesus’ time and before. This quote is from Berachot 16b.

A major source for this article is Deliver Us From Evil, by Dr. Randall Buth, in the online jounal www.JerusalemPerspective.com.