by Lois Tverberg

Throughout the Bible there is a recurring image that is mysterious to modern, Western Christians: blood. We like abstract concepts like atonement and salvation, but if we really want to understand these ideas as the Bible explains them, we need to understand its cultural language, which includes the imagery of blood.

Throughout the Bible there is a recurring image that is mysterious to modern, Western Christians: blood. We like abstract concepts like atonement and salvation, but if we really want to understand these ideas as the Bible explains them, we need to understand its cultural language, which includes the imagery of blood.

The ancient Hebrews thought in concrete ways, expressing abstract ideas in terms of things they could see, touch and smell. In Hebrew, a person is not stubborn, he is “stiff-necked”; God is not slow to anger, he has “long nostrils”; God is not jealous, he is “red-faced.”

When God was speaking to them about blood, he spoke to them in this image-based language. Rather than being woodenly literal about what God said about blood, our best way to understand it is to imagine how they saw it, and then translate it into our own language.

Life is in the Blood

The ancient Hebrews believed that the blood of a creature contained its life. They could observe that a person or animal bleeding from a wound will grow faint, and with enough blood loss will die. Because no other damage had to be done than to let the blood run out, it was logical to observers that the life of the animal or person was going out with the blood.1 This has been a common understanding throughout the history of the world, and the sacred awe associated with blood is still held by traditional African cultures even now.2 The Bible reinforces that belief by saying:

For the life of the flesh is in the blood… For as for the life of all flesh, its blood is identified with its life. (Lev. 17:11, 14)

Because of this belief, it was understood that imbibing the blood of a powerful animal would allow a person to acquire its “life,” to take on some of its power: this is still practiced in animistic cultures today. The Bible is unique among documents of its time for forbidding the consuming of blood.

Although they could kill and eat animals, God himself owned the “life” of the creature, and the blood had to be given back to him by being poured on an altar, or on the ground.3 We read this as an outmoded regulation from ancient times. We should instead look at it as if God was speaking their language in order to teach them a profound idea — that God alone is the creator and possessor of the life of every creature. He says:

But you must not eat meat that has its lifeblood still in it. And for your lifeblood I will surely demand an accounting. I will demand an accounting from every animal. And from each man, too, I will demand an accounting for the life of his fellow man. Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed; for in the image of God has God made man. (Gen 9:4-6)

This helps us to understand the odd regulation about not eating the meat of strangled animals in Acts 15:20. The early church had made a decision that the Gentiles entering the church did not need to take on the full requirements of Torah observance, but they needed to observe the basic laws that God had given even the Gentiles.

They noted that the prohibition of eating animals with the blood still in them came from Genesis, not from the laws of Moses that were given specifically to the Israelites. They wanted them to abandon this practice used in idolatrous ceremonies to show that they had abandoned idol worship, and out of respect for God’s ownership of every life.

The Preciousness of Human Life

An important moral law God was teaching through the prohibition of bloodshed in Genesis 9:6 is that human lives are precious to God — he made us in his image, so by taking a human life, we are destroying the one thing in creation that uniquely bears God’s likeness. The sanctity of life may seem second nature to us, but the idea was unprecedented in ancient, pagan cultures.4

We don’t often contemplate how this singular idea has transformed our entire civilization to the point that it is what makes us “civilized.” Hospitals, orphanages and charities of all types have arisen our of the belief that human life must be preserved at any cost.

Jews have a profound way of expressing this idea that comes from the first case of shedding of innocent blood, Cain’s murder of Abel. God says to Cain,

“The voice of your brother’s blood (bloods, literally) is crying to Me from the ground.” (Gen. 4:10)

The Hebrew word for blood is dam, and the plural is damim. When the Bible talks about murder, or “bloodguilt,” it usually uses the plural form, damim. Using the logic that the blood contains the life of a person, to speak of blood in the plural implies that a murder doesn’t just take the life of one person, it takes the lives of many.

Jews therefore have a tradition that the voice of the “bloods” crying out from the ground was actually the voices of all of the future descendants of Abel that would have ever lived. From this they have a saying, “To take the life of one person is like taking the life of a whole world, and to save the life of one person is like saving a whole world!”5

Innocent Blood

Related to this understanding that the blood contained the life of a person was the idea that the blood of an innocent victim of murder would curse the ground. (Of course, blood didn’t literally have to be shed — the phrase “to shed innocent blood” meant the murder of innocent people, in whatever manner.) In many cultures in Africa today, the land must be abandoned, and never farmed again until atonement is made for the bloodshed.6

The ancient person would understand that this was why Cain could never farm again, because the land was cursed by his murder. They would also see it as the reason for the flood — to both destroy the wicked people of the earth, and purify the earth itself from the blood that had been shed.

The “shedding of innocent blood” was such a great crime that the only way to get rid of it was to take the life of the murderer. If the murderer was unknown, an animal had to be sacrificed to atone for the murder. Otherwise, if not atoned for, it eventually would bring terrible judgment.

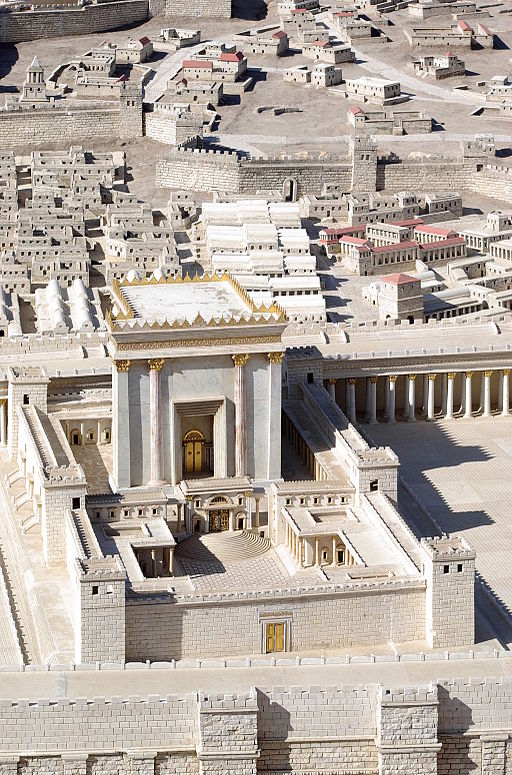

The sin that finally caused God to let kingdom of Judah be destroyed was the shedding of innocent blood. This was because of the murder of the prophets and faithful Jews, and the abhorrent practice of infant sacrifice:

The LORD sent Babylonian, Aramean, Moabite and Ammonite raiders to destroy Judah… Surely these things happened to Judah according to the LORD’s command, in order to remove them from his presence because of the sins of Manasseh and all he had done, including the shedding of innocent blood. For he had filled Jerusalem with innocent blood, and the LORD was not willing to forgive. (II Kings 24:2-4, edited)

Jesus also said that this was would bring judgment on His generation as well, when Jerusalem would be besieged and the temple burned. He said that God would punish the corrupt temple leaders because of the righteous blood that they shed:

And so upon you will come all the righteous blood that has been shed on earth, from the blood of righteous Abel to the blood of Zechariah son of Berekiah, whom you murdered between the temple and the altar. (Matt 23:35)

Covenants Sealed with Blood

Another place blood is always seen is in the formation of covenants. In Genesis 16, when God makes a covenant with Abraham to give him the land, he tells him to sacrifice five animals and make a blood path, an ancient method of covenant-making. God later asks Abraham to take on the covenant of circumcision, where his own blood is shed, as is that of all his male descendants (Genesis 17:10).

When God makes the covenant with Moses and the Israelites at Mt. Sinai, they are sprinkled with blood to seal the covenant (Ex. 24:8). In other ancient cultures, two men making a covenant would cut their arms and mingle the blood, saying by that act that they were now bound to each other by the covenant, as their lives were intertwined by their blood. A covenant was a way to form a new peaceful relationship between two parties, and the blood of the covenant signified that their very lives were devoted to it.7

Blood Used for Atonement

In the Levitical laws, God explains that he will allow His people to atone for their sins through the blood of animals. It is a substitution of their blood for that of the guilty person, the animal’s life for the person’s life. Leviticus 17 explains that because the blood represents the life of the animal, the blood makes atonement for the life of the person:

In the Levitical laws, God explains that he will allow His people to atone for their sins through the blood of animals. It is a substitution of their blood for that of the guilty person, the animal’s life for the person’s life. Leviticus 17 explains that because the blood represents the life of the animal, the blood makes atonement for the life of the person:

For the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have assigned it to you for making atonement for your lives upon the altar; it is the blood, as life, that effects atonement. (Lev. 17:11)

Once again God is using a cultural language that they would understand: by allowing them to use animal blood for atonement, he is beginning to teach them that although sin demands punishment, he will provide a way for them to find forgiveness for their sins by means of a substitution. He is pointing ahead to the ultimate substitutionary death of Christ.

The Blood of Christ

Now we can see some of the logic behind Jesus’ words at the Last Supper, when he brings new significance to the third cup of the Passover meal, the Cup of Redemption:

Then he took the cup, gave thanks and offered it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. (Matt. 26:27-28)

Here we see Jesus using the image of blood in two ways: he is explaining that the shedding of his blood on the cross is the substitution of his life for ours, granting us eternal redemption from our sins. He is also saying that his blood ratifies a new covenant between God and man, whereby we now have a new relationship with God if we personally partake of Christ’s atonement.

Here we see Jesus using the image of blood in two ways: he is explaining that the shedding of his blood on the cross is the substitution of his life for ours, granting us eternal redemption from our sins. He is also saying that his blood ratifies a new covenant between God and man, whereby we now have a new relationship with God if we personally partake of Christ’s atonement.

The blood of Christ is both an atonement for sin and the seal of a new covenant, and every time we take communion, we remind ourselves of our forgiveness. We remind ourselves of our new loving fellowship with God, because of the covenant sealed by the blood of Christ.

~~~~

1 “Blood,” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, available online at studylight.org.

2 Milly Erema, “Teaching the Bible Using Ugandan Cultural Resources with Specific Reference to the Old Testament,” Western Theological Seminary Master’s Thesis, 2001.

3 Deuteronomy 16:23.

4 Nahum Sarna, Exploring Exodus, p 177 Schocken Books, 1996.

5 Nahum Sarna, JPS Torah Commentary, Genesis, p. 34, Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

6 See reference 2.

7 Article, “Covenants,” Jewish Encyclopedia, p 318-322, Funk and Wagnalls, c.1906-1910. Available online at jewishencyclopedia.com.

Photos: Official Navy Page from United States of AmericaMass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Jonathan Sunderman/Mass Communication Specialist 3r [Public domain], William-Adolphe Bouguereau [Public domain], Branislav Belko on Unsplash, Eczebulun [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most important day of the year for Jews. It begins before sunset the night fore, and includes a 25 hour fast from both food and water, and ceasing of all work. It is a day set aside to “afflict the soul,” to ask for atonement for the sins of the past year. Even Jews who otherwise are not observant will observe this day.

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most important day of the year for Jews. It begins before sunset the night fore, and includes a 25 hour fast from both food and water, and ceasing of all work. It is a day set aside to “afflict the soul,” to ask for atonement for the sins of the past year. Even Jews who otherwise are not observant will observe this day.