Welcome to En-Gedi…

Featured Article: (from Parables and Stories)

Featured Article: (from Parables and Stories)

Does God Forget Sins?

by Lois Tverberg

The Bible has many difficult ideas for us to grasp, and some seem quite impossible. We know that God is infinite and created all things, and knows the future and the ancient past. Often, however, we read that God “remembered” something or “forgot” something, which implies that he has limits to his mental capacity. In particular, we read that if we repent, God will not remember our sins:

I, even I, am the one who wipes out your transgressions for My own sake, And I will not remember your sins. (Is. 43:25)

In moments of anger God says that he will forget his people, as if an infinite God can forget anything:

Therefore behold, I will surely forget you and cast you away from My presence, along with the city which I gave you and your fathers. (Jer. 23:39)

Another related question to this one about God “forgetting” is what God expects of us, since when God forgives, it says he does not remember our sins. Does God expect us to actually forget the sins committed against us as part of our forgiveness of them? Does he feel that we haven’t truly forgiven unless we have forgotten the sin as well? Who really can do that?

Hebraic Insights on This Dilemma

We can get some help with this difficulty when we look at the concepts contained in the Hebrew words. Often our difficulties in reading the Bible come from a lack of understanding of this. Because Hebrew is a word-poor language, most words have a wider scope of meaning than in English.

Usually the usage overlaps our English words, and if we know that there is an extended meaning, it enriches the passage for us. Sometimes, however, our English usage doesn’t really fit a passage well at all, and we need to learn the Hebraic definition in order to understand the original intent of the passage.1

Understanding the Hebrew words that we translate into “remember” and “forget” can give us several important insights. In English, our definition of the word “remember” focuses entirely on the idea of recalling memories and bringing ideas into our thoughts. To forget is the exact opposite: to fail to bring a certain memory to mind. Our concept is concerned entirely with mental activity and whether or not information is present or not. So for us, remembering and forgetting is entirely a mental activity.

Understanding the Hebrew words that we translate into “remember” and “forget” can give us several important insights. In English, our definition of the word “remember” focuses entirely on the idea of recalling memories and bringing ideas into our thoughts. To forget is the exact opposite: to fail to bring a certain memory to mind. Our concept is concerned entirely with mental activity and whether or not information is present or not. So for us, remembering and forgetting is entirely a mental activity.

In contrast, in Hebrew, the word zakor, “remember,” has a much wider definition.2 It includes both remembering as well as the actions taken because of remembering. It can often imply that a person did a favor for someone, helped them, or was faithful to a promise or covenant. This helps us to understand verses like the following:

But God remembered Noah and all the beasts and all the cattle that were with him in the ark; and God caused a wind to pass over the earth, and the water subsided. (Gen. 8:1)

Then God remembered Rachel, and God listened to her and opened her womb. (Gen. 30:22)

The passage about Noah doesn’t mean that God suddenly recalled that a boat was floating out on the flood, and then realized that he should do something about it. When God remembered Noah, he acted upon his promise that Noah’s family and the animals would be rescued from the flood.

In the other passage, God did a favor for Rachel by answering her prayer for a son. The verb is focused on the action, not the mental activity on God’s part. God paid attention to her needs, listened to her prayer, and answered it. Here, “remember” means “to intervene,” focusing on God’s action.

The Idea of Forgetting

Interestingly, the Hebrew words for forget, shakach and nashah are not the exact opposites of zakor, “remember.” To “forget” in Hebrew also means to ignore, neglect, forsake, or willfully act in disregard to a person or covenant. It is to act as if you have forgotten. Frequently the Bible says, “Do not forget the Lord your God” meaning, do not forsake him, be loyal to him.

Interestingly, the Hebrew words for forget, shakach and nashah are not the exact opposites of zakor, “remember.” To “forget” in Hebrew also means to ignore, neglect, forsake, or willfully act in disregard to a person or covenant. It is to act as if you have forgotten. Frequently the Bible says, “Do not forget the Lord your God” meaning, do not forsake him, be loyal to him.

To “forget” usually has a negative connotation close to what the American slang term “to blow off” means today. For instance,

So watch yourselves, that you do not forget the covenant of the LORD your God which he made with you, and make for yourselves a graven image in the form of anything against which the LORD your God has commanded you. (Deut. 4:23)

The idea is that they would willfully ignore their covenant, not necessarily forget that they made it. In the passage discussed earlier (Jer. 23:39), when God says he will “forget” his people, it means that he will spurn them as his people, not lose their memory from his mind.

When we read with an emphasis on action, rather than mental activity, it clarifies that God is not necessarily losing information from his mind. For instance:

How long, O LORD? Will You forget me forever? How long will You hide Your face from me? (Psa. 13:1)

The psalmist is saying “why do you ignore my prayers and not intervene in my crisis?” God doesn’t forget, but sometimes it seems as if he does.

Remembering Sins

The key to understanding is in the phrase “remembering sins.” The idea of “remembering sins” takes the idea of action and puts it into a negative framework. It really contains the idea that God give the person what he deserves for the sin — he will punish sin, not just keep it on his mind. We find it in this poetic parallelism, where one phrase is synonymous with the other:

They have gone deep in depravity as in the days of Gibeah;

He will remember their iniquity, he will punish their sins. (Hosea 9:9)

To “remember iniquity” is the same as to “punish their sin.” It is automatically negative, implying that God will intervene to bring justice. So to not remember sins is to decide to not punish them:

If a wicked man restores a pledge, pays back what he has taken by robbery, … he shall surely live; he shall not die. None of his sins that he has committed will be remembered against him. (Ezekiel 33:15-16)

The man who has been forgiven in the passage above will not have his sins “remembered against” him: implying that he will not be punished for them. Because Hebrew focuses on the action rather than the thought, it doesn’t imply that God somehow has no memory of them in his infinite mind. It means that he has decided not to act upon them.

Interestingly, “forget” is almost never used in combination with sins! The Bible does say often that God does “not remember” our sins, meaning that when he forgives, he chooses to never act on them.

Implications From These Meanings

By understanding that Hebrew focuses on action rather than on mental recall, we can now get some insight on how God can “forget” people, but yet not forget. Or how he can choose not to “remember” our sins, and yet not lose them from his memory. God chooses to put them aside, to ignore them and not bring them up after we have repented.

Any married person knows what this is like — to be hurt by a spouse yet “decide to forget” — to put it out of your mind even though the memory doesn’t goes away. A person who loves another who has hurt him or her simply chooses not to act in revenge for the sin. Once you have done this, the memory itself tends to decline.

Any married person knows what this is like — to be hurt by a spouse yet “decide to forget” — to put it out of your mind even though the memory doesn’t goes away. A person who loves another who has hurt him or her simply chooses not to act in revenge for the sin. Once you have done this, the memory itself tends to decline.

The Hebraic idea of “remembering sins” really encompasses the idea of vengeance and punishment for them, not just knowing about them. When God says he will not remember our sins, he is deciding to forgo prosecuting us for them. This can be very freeing in terms of understanding God’s expectations for us.

When a person has hurt us repeatedly, we often wonder whether forgiveness means to pretend that the person won’t act the same way again. Are we allowed to protect ourselves, even if we hope they’ll change? The idea that we can decide not to “remember” someone’s sins in terms of seeking revenge is very freeing, because it allows us to discern the difference between remembering with a heart of revenge, versus remembering in order to make a situation better.

In some ways, if God could simply delete things from his memory banks, he would have a much easier job than humans who can’t erase their memories. When we forgive a person, we need to choose to put aside our grievances, and often we need to do that over and over again as the memory returns to our minds.

It shows more love to be hurt and choose to not remember many times than to simply be able to forget about an incident. The more we love one another, the easier it become to remove the memory of the past from our minds. In this sense, perhaps God’s infinite love really does entirely remove our sins from his infinite mind.

~~~~

1 See En-Gedi’s article “Listening Through Jesus’ Ears“

2 Another good article on this subject is “The Biblical Concept of Remembrance,” by Doug Ward.

Photos: Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash, Peter Pryharski on Unsplash, Truthout (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Does God Want Us To Fear Him?

by Lois Tverberg

Understanding the extended meanings of Hebrew words often corrects our misunderstandings of the Bible and explains things that seem to not make sense. Sometimes they can even change our attitude toward God! This is what happens when we understand the broader meaning of the word “fear,” yirah, in Hebrew, and especially in the context of the “Fear of God,” a common expression throughout the Bible.

Understanding the extended meanings of Hebrew words often corrects our misunderstandings of the Bible and explains things that seem to not make sense. Sometimes they can even change our attitude toward God! This is what happens when we understand the broader meaning of the word “fear,” yirah, in Hebrew, and especially in the context of the “Fear of God,” a common expression throughout the Bible.

The idea that we should “fear the Lord” is found hundreds of times in the Old Testament. To many people this is a source of anxiety, and may make us not want to read about the God who appeared to require fright and dread among his people.

It may surprise people to know that even in the New Testament, the “fear of God” is often found. The Gentiles who worship the God of the Jews are called “God-fearers” and the early church was said to be built up in the “fear of the Lord” (Acts 9:31). Paul even speaks of the “fear of Christ” in Ephesians 5:21.

This is because the “fear of the LORD” was an extremely rich idea that goes far beyond our literal understanding, and is wonderfully positive in application. By understanding the Hebrew meaning of “fear,” and the rich Jewish thinking about the “Fear of the Lord,” we can shed great new light on this issue.

The key to understanding the Hebraic idea of “fear” is to know that like many Hebrew words, it has a much broader sense of meaning than we have in English. To us, “fear” is always negative: it is the opposite of trust, with synonyms of fright, dread and terror.

In Hebrew, it encompasses a wide range of meanings from negative (dread, terror) to positive (worship, reverence) and from mild (respect) to strong (awe). In fact, every time we read “revere” or “reverence,” it comes from the Hebrew word yirah, literally, to fear. When fear is in reference to God, it can be either negative or positive. The enemies of God are terrified by him, but those who know him revere and worship Him, all meanings of the word yirah.

How Should We “Fear the Lord”?

Many Christians understand “the Fear of the LORD” as the fear of the punishment that God could give us for our deeds. It is true that everyone should realize that they will stand at the judgment after they die, but a Christian who knows his sins have been forgiven should not have this kind of fear of God anymore: although many still do.

Many Christians understand “the Fear of the LORD” as the fear of the punishment that God could give us for our deeds. It is true that everyone should realize that they will stand at the judgment after they die, but a Christian who knows his sins have been forgiven should not have this kind of fear of God anymore: although many still do.

People who have been steeped in this kind of “punishment mindset” have a very hard time loving God. This is what John speaks against when he says, “There is no fear in love; but perfect love casts out fear, because fear involves punishment, and the one who fears is not perfected in love.” (1 John 4:18).

Interestingly, in rabbinic thought, fearing God’s punishment is also understood to be an incomplete and inferior understanding of the term Yirat Adonai, “Fear of the Lord.”1 At its core is self-centeredness: what will happen to me because of God’s knowledge of my deeds?

Knowing the broader implications of the word “fear” in Hebrew, the rabbis came to a different conclusion, that the best understanding of the term Yirat Adonai is of having awe and reverence for God that motivates us to do His will.

This helps many passages make sense and show why the “Fear of the Lord” is so highly praised in the Bible:

The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom, and knowledge of the Holy One is understanding. (Prov. 9:10)

In the fear of the LORD there is strong confidence, and his children will have refuge. The fear of the LORD is a fountain of life, that one may avoid the snares of death. (Prov. 14:26-27)

The “fear of the Lord” in these passages is a reverence for God that allows us to grow in intimate knowledge of Him. It teaches us how to live, and reassures us of God’s power and guidance. It gives us a reverence of God’s will that keeps us from getting caught in sins that will destroy our relationships and lives.

A Sense of God’s Presence

One aspect of Yirat Adonai that the Jewish people have focused on is the idea that we should be constantly aware of the presence of God. Over the top of Torah closets in many synagogues is the phrase “Know Before Whom You Stand,” reminding the congregation that an infinitely powerful God is close at hand.

People sometimes tell stories of how on the death bed of a family member, they had a strong sense of the presence of God, and have felt great reassurance from it, bringing a sense of awe for him at that time. Or in worship, there is no greater thrill than to feel spine-tingling awe at the grandeur of God.

In this sense, to “fear” God is to be filled with awe, and it is one of the most profound experiences of our lives, spiritually. We can see why the “fear of the LORD” as an awesome sense of his presence around us is really the essence of our life of faith.2

In this sense, to “fear” God is to be filled with awe, and it is one of the most profound experiences of our lives, spiritually. We can see why the “fear of the LORD” as an awesome sense of his presence around us is really the essence of our life of faith.2

In some areas of Christianity, there is a lack of thinking of God as present with us now. God is spoken of in abstract terms, as if he is a theory rather than a being, and we sound live like we don’t expect to have any interaction with him until we die.

This is partly because of our Greek heritage, which focused on the spiritual world as being utterly apart from the material world. While our culture may have taught us that, the biblical witness is that God’s Spirit is very much present in the world with us now.

There is an enormous difference between study of the Bible that has Yirat Adonai, reverence for God, and a purely intellectual approach. The emphasis on reverence for God in Judaism is illustrated by a famous quote from Abraham Heschel that says that while Greeks (Europeans and Americans) study to comprehend, Jews study to revere. Higher education in biblical studies in Western countries tends to be entirely intellectual, and Christians who take academic Bible classes often find them dry.

What they are looking for is God’s voice speaking through the scriptures, and to find it they need Yirat Adonai. The rabbis had an excellent saying: that a scholar who does not have Yirat Adonai is like a man who owns a treasure chest and has the inner keys but not the outer keys.3 He has a treasure but can’t get at it. To study the Bible without reverence is a dry enterprise that will never unlock its true meaning.

Our Moral Foundation

Another thing Yirat Adonai gives us is an inner moral foundation. When we know God knows our thoughts, we are compelled to act not just for what other people think, but for what God thinks. This is what Paul refers to in Col. 3:22 when he says “Slaves, in all things obey those who are your masters on earth, not with external service, as those who merely please men, but with sincerity of heart, fearing the Lord.” Reverence of God gives us an inward sincerity, because we don’t do things just for external appearances, but to please God who knows our heart.

One humorous old rabbinic story illustrates this point:

A great rabbi once caught a ride on a horse-drawn wagon, and as the wagon passed a field full of ripe produce, the driver stopped and said, “I’m going to get us some vegetables from that field. Call out if you see anyone coming.” As the driver was picking vegetables, the rabbi cried out, “We’re seen! We’re seen!” The frightened man ran back to the wagon, and looked and saw no one nearby. He said, “Why did you call out like that when there was nobody watching?” The rabbi pointed toward heaven and said, “God was watching. God is always watching.”4

An awareness of God’s presence will motivate us to obey him. We may still think of it as a fear of punishment, but it does not have to be this way in believers. When we have reverence for someone, we feel terrible to know we’ve disappointed them.

In times of my life when I’ve worked for someone whom I greatly respected, their praise for my work has been critical to me. Or, when we love someone, we earnestly want their approval on our lives. Indeed, the “fear of Christ” that Paul talks about should really be a sense of Christ’s majesty, and a longing to please him. When we know he is always with us, it causes us to try to live as the disciple he wants us to be.

Yirat Adonai – What God desires most

Amazingly, God says that what he truly desires is that we “fear Him”:

Now, Israel, what does the LORD your God require from you, but to fear the LORD your God, to walk in all His ways and love Him, and to serve the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul… (Deut 10:12)

In this passage, the first words are to fear God, and they are equivalent with the rest of the passage — to fear God is to revere him, which will cause us to walk in his ways and serve him with all our being. Properly understood, there is no greater desire that we should have than to have a “fear of the LORD,” an awesome sense of God’s presence in our lives that will transform us into the people that he wants us to be.

~~~~

1 From “Fear of YHWH and Hebrew Spirituality” a lecture by Dwight Pryor, president of the Center for Judaic-Christian Studies. This was from the monthly Haverim audio tape series, October 2003. These tapes are a very rich resource — see jcstudies.com to sign up.

2 In an effort to constantly have a sense of God’s care for us, the Jews from Jesus’ day up until the present have had a wonderful tradition of uttering prayers to “bless the Lord” many times a day to remind themselves that He is the source of every good thing. When I’ve tried this in my own life, sensing God’s immediacy becomes unavoidable. For more, see “The Richness of Jewish Prayer.”

3 From the Talmud, Tractate Shabbat 31b. See the article “Fear of God” at jewishencyclopedia.com.

4 As quoted by Joseph Telushkin in The Book of Jewish Values, p 10. Copyright 2000, Bell Tower. ISBN 0-609-60330-2. (This is an outstanding book on practical ethics and how we should live: a favorite of mine.)

Photos: Sonya [CC BY-SA 2.0], Mélody P on Unsplash, Joshua Earle on Unsplash, Zac Durant on Unsplash

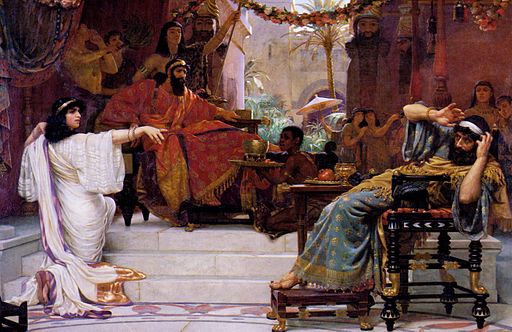

Esther: The Rest of the Story

by Lois Tverberg

The feast of Purim is the annual celebration of the salvation of the Jews from destruction that is described in the book of Esther. It is the story of how Esther and her uncle Mordecai saved the Jewish people in about 500 BC in Persia.

In the story, an advisor to the king, Haman, was angered by the fact that Mordecai would not bow down to him, so he convinced the king to issue an edict calling for the destruction of the entire Jewish people. Esther saved the Jews by risking her life to plead to the king to annul the edict, and by exposing Haman’s plot against them.

In the story, an advisor to the king, Haman, was angered by the fact that Mordecai would not bow down to him, so he convinced the king to issue an edict calling for the destruction of the entire Jewish people. Esther saved the Jews by risking her life to plead to the king to annul the edict, and by exposing Haman’s plot against them.

Interestingly, the name of God is never mentioned in the story, although his hand is clearly present in every event. A tradition that celebrates this is to dress up in costumes and masks on Purim, to celebrate that sometimes even God wears a “mask” — that he is present even when he doesn’t seem to be. The feast is often celebrated with silly plays (shpiels) based on the story of Esther, and is lighthearted to celebrate God’s care for his people even when he doesn’t seem to be present.

The Longer Epic of this Story

The story of Esther is actually the culmination of a much longer saga that stretches over 1300 years in the life of Israel. A key to the story is the identity of Haman, who is described as an “Agagite.”

Agag was the king of the Amalekites in Saul’s time, so Haman is an Amalekite. While we hear about so many “ite” groups in the Old Testament that they all seem to be the same, the Amalekites have the distinction of being thought of by Jews as Israel’s worst enemy of all time.

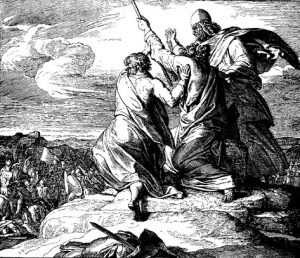

The Amalekites were the first nation that ever attacked Israel, and they did this almost immediately after Israel had left Egypt, when they first entered the wilderness (Exodus 17). Being the first to attack, they became symbolic of all of the nations that want to destroy Israel.

The Amalekites were the first nation that ever attacked Israel, and they did this almost immediately after Israel had left Egypt, when they first entered the wilderness (Exodus 17). Being the first to attack, they became symbolic of all of the nations that want to destroy Israel.

The Amalekites also chose a particularly cowardly and brutal way to attack, by coming from the rear and killing the elderly and weaker Israelites that were straggling behind. As a result, God was furious with the Amalekites, and singled them out for divine judgment:

Then the LORD said to Moses, “Write this in a book as a memorial and recite it to Joshua, that I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven.” Moses built an altar and named it The LORD is My Banner; and he said, “The LORD has sworn; the LORD will have war against Amalek from generation to generation.” (Ex. 17:14-16)

The words seem contradictory — that God will be continually at war with Amalek, and yet he will blot them out. How can both be true? But oddly they are. The Amalekites continually plagued the Israelites throughout their history. When Israel first tried to enter the promised land but lost faith in God, the Amalekites were there to attack them.

Later, Saul was given the command to destroy them and leave nothing alive, even children or animals (1 Sam. 15:7-9). He instead disobeyed God and kept some of the best animals for himself, and let King Agag live.

According to Jewish thought, a demonic hatred of Israel was associated with that nation, and by taking any booty that was contaminated by that spirit, or letting anything of theirs escape, Saul allowed this spirit of destruction to come back to terrorize Israel again. King David and King Hezekiah also fought against them during their reigns, and they were back again during the time of Esther.

In the story of Esther there are several motifs hinting that the Amalekites are back to try once again to destroy Israel. Often when the text speaks of Haman as an enemy of the Jews, it specifically emphasizes his nationality as an “Agagite,” a descent of the Amalekite king:

Then the king took his signet ring from his hand and gave it to Haman, the son of Hammedatha the Agagite, the enemy of the Jews. (Esth. 3:10)

For Haman the son of Hammedatha, the Agagite, the adversary of all the Jews, had schemed against the Jews to destroy them and had cast Pur, that is the lot, to disturb them and destroy them. (Esth. 9:24)

There are more parallels between this story and that of Saul that hint that this is the completion of Saul’s unfinished work. The narrator is explicit in showing that Mordecai and Esther are from the family of Saul, fellow Benjaminites and descendants of his line (Esth. 2:5-6).

While Saul kept some of the booty for himself, the story of Esther points out repeatedly that the Jews took none of the plunder after they were allowed to kill Haman and his descendants. By not committing Saul’s sin, they finally had victory.

Help for Hard Passages

This story has helped me understand some of the difficult commands of God. God had said to Saul,

Now go and strike Amalek and utterly destroy all that he has, and do not spare him; but put to death both man and woman, child and infant, ox and sheep, camel and donkey. (1 Sam. 15:3)

After Saul disobeyed God, not through showing mercy to the people, but instead by keeping some of the best livestock for himself, God said that he had regretted making Saul king, and decided to remove him from the throne.

It shocks us that God could give such a horrible command and be so angry to see it not carried out. God’s harsh command to Saul to destroy every living thing of the Amalekites was because this was a nation bent on the destruction of Israel, without whom the world would have no Savior. Israel was nearly annihilated in Esther’s time because of Saul’s disobedience. Sometimes God’s commands are incomprehensible, but if we had his perspective, we would see his logic.

The Epic Goes On

Interestingly, in Jewish thought, even though the Amalekites are no more, the demonic spirit of Amalek has lived from ancient times even until today. The forefather of the nation, Amalek, was Esau’s grandson. According to legend, when Esau was old, he said to his grandson Amalek: “I tried to kill Jacob but was unable. Now I am entrusting you and your descendents with the mission of annihilating Jacob’s descendents — the Jewish people. Carry out this deed for me. Be relentless and do not show mercy.” (This isn’t biblical, but it shows their attitude toward the Amalekites.)

Throughout history, there has been relentless anti-Semitism, persecution and attempts by other nations to annihilate the Jewish people. Hitler was considered to be a spiritual “descendant” of Haman. God has been continually at war with the spirit of Amalek from generation to generation, and only in the final judgment will this spirit of hatred be blotted out.

~~~~

(1) Alfred Edersheim, Bible History: Old Testament, 1890. Chapter 9, available at this link.

(2) JPS Torah Commentary on Deuteronomy, by Jeffrey Tigay. Jewish Publication Society, 1996, p 236.

(3) E. E. Halevy, Amalekites, Encyclopedia Judaica CD-ROM, Version 1.0, 1997

Photos: Otto Semler [Public Domain], Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld [Public domain], Ernest Normand [Public domain]

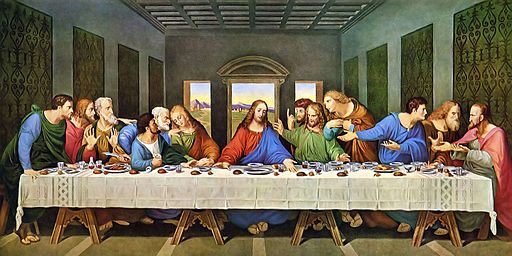

Has Da Vinci Painted Our Picture of Jesus?

by Bruce Okkema

Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” has come to be one of the most famous paintings of all time, yet many do not know its original setting. The image has been reproduced countless times the world over, and has become the subject of many paintings itself.

Because this painting is so well known, it has been highly influential in establishing a picture in our minds of what the last night before Jesus’ death must have been like. Unfortunately it is the wrong picture! Nearly every detail in the picture is culturally inaccurate.

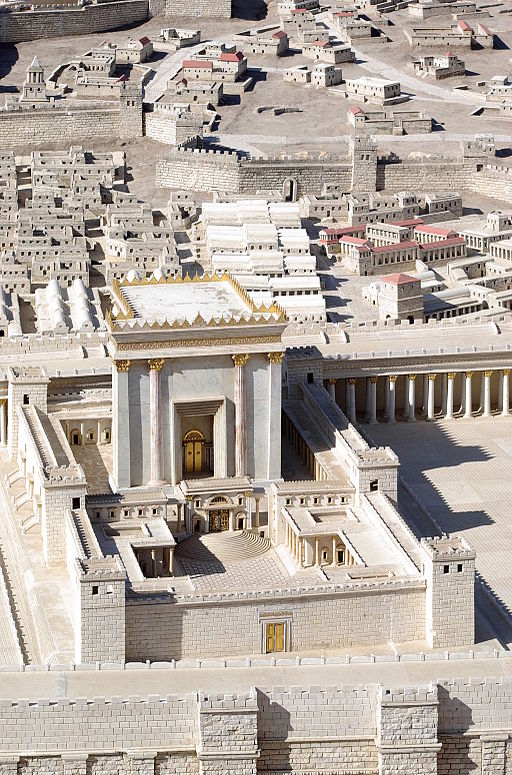

To list just a few: the people in the picture look European, certainly not Semitic. The supper that Jesus was participating in was a Jewish Passover Seder — Pesach in Hebrew. It was always celebrated after sundown, not with the blue sky as we see. These feasts have usually been celebrated with family, so there may have been other women and men dining with them, and children of all ages.

Jesus would have not been seated in the middle of a long table, he would have reclined on a couch or pillow on the floor, leaning on his left elbow. He certainly would not have been eating fish and leavened bread loaves! Rather, he would have been eating lamb, bitter herbs, and unleavened bread as was commanded in Exodus 12. To leave lamb off the menu for Passover is to forget an essential detail of the supper in which Jesus presents himself as the true lamb of Passover.1

At the point in the Seder when Jesus took the bread, broke it and said, “this is my body broken for you” (Luke 22:19), those present would have seen him hold up the unleavened bread, the “bread of affliction” that reminded them of God’s redemption from Egypt. It was free from leaven, representative of sin in this case, just as a pure sacrifice offered at the temple had to be free of leaven. Without that image, we miss the message in Jesus’ powerful words.

Does it matter that we have the wrong picture? It does if we want to understand Jesus — if we want to understand his culture. Our human mind always associates images with our thinking process; in one sense, we think in terms of pictures. If we use the wrong picture, we will likely miss the message, and the story will sound different than intended.

Da Vinci never intended for this painting to become the theological icon that it has become. The peculiar details that he incorporated into the painting (for example, 25 hands for 12 disciples) are the subject of many books, but it is certain that historical accuracy was not his objective.

Ironically, Da Vinci’s painting which has taken Jesus out of his context, has itself has been taken out of context. We usually see the image portrayed as if it were a painting on canvas, when actually it was a mural measuring 15’ x 29’ painted on a wall in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy.

Da Vinci was commissioned in 1494 by a patron of the town, Duke Ludovico, to paint a fresco in the monk’s dining hall there. Fresco is a technique using water-based paint applied directly to plaster while it is still wet, and requires the artist to work quickly before the plaster dries. Da Vinci simply could not paint this way; he wanted time to consider, to go back weeks, months, or even years later to add things.

Da Vinci was commissioned in 1494 by a patron of the town, Duke Ludovico, to paint a fresco in the monk’s dining hall there. Fresco is a technique using water-based paint applied directly to plaster while it is still wet, and requires the artist to work quickly before the plaster dries. Da Vinci simply could not paint this way; he wanted time to consider, to go back weeks, months, or even years later to add things.

So he decided to lay down a surface on the wall that would allow him to work as he usually did.2 He invented a technique of applying a mixture of oil and tempera over two layers of plaster, a technique that unfortunately proved to be unsuccessful. He could not have predicted that these materials would succumb to the attacks of pollution or humidity. Even during Leonardo’s lifetime the irreversible process of deterioration set in and pieces started flaking off the painting.3

The painting has undergone numerous restorations and remarkably survived a bombing raid in August of 1943, when a protective curtain hung over it prevented irreparable damage. Even so, the painting is just a shadow of what it originally was; its now dulling, neutral colors were once vivid and luminous.

The painting has undergone numerous restorations and remarkably survived a bombing raid in August of 1943, when a protective curtain hung over it prevented irreparable damage. Even so, the painting is just a shadow of what it originally was; its now dulling, neutral colors were once vivid and luminous.

As stated earlier, it was commissioned for a dining hall, but because we usually see the image cropped, we don’t realize that it was actually quite ingenious in its original setting.

Da Vinci made it look as though Jesus and his disciples were eating right there with the monks. The table at which the disciples sat was just like the ones the monks used, as were the dishes, the glassware, and even the tablecloth, with its blue embroidery and fringed ends. The architecture in the painting itself is an extension of the real architecture of the room in which it was painted. From the place occupied by the prior of the convent at meal-times, the painting appears as a continuation of the real refectory building, and the figure of Christ seems to offer the elements from the picture to the real spectators outside it. He chose to paint the moment when Jesus had just told his friends that one of them would soon betray him. The disciples were shown reacting in individual ways, with gestures and facial expressions that were very theatrical and full of emotion.4

Da Vinci’s intention was to present a character study, which is one of the reasons the painting took him four years to complete. The final work was preceded by a long series of preparatory drawings which are today in various collections around the world. The figures which gave Leonardo the greatest trouble were those of Christ and Judas, so much so that while the work was in progress, the prior of the convent went to the Ludovico, the Duke who had commissioned the work, to complain because they had not yet even been sketched.

“Perhaps the fathers know how to paint?” retorted Da Vinci to Ludovico. “How can they judge an artistic creation? For one whole year I have gone every day, morning and evening, to the Borghetto, where the scum of humanity live, to find a face that will express the villainy of Judas, and I have not yet found it. Perhaps I could take as a model the prior who has been complaining about me to your Excellency.”5

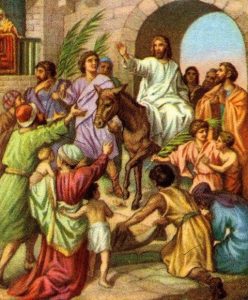

Understanding that Jesus was celebrating the Passover meal is critical for understanding how he fulfills its promises of redemption, and brings it to a new level in the lives of his followers. From the time Abraham told Isaac in Genesis 22:8 that “God himself will provide the lamb for the offering, my son” until now, the story of God’s redemption is the story that we have to get right.

Telling the story of how God himself redeemed his people out of Egypt, gave the covenant, and dwelled among them — all of this is commemorated during the Seder. It is vital to understanding Jesus and his ministry as the great fulfillment of that first act of redemption by God. The story is all about the sacrifice, the covenantal meal, blessing, teaching, and making disciples. This needs to be conveyed accurately in words and in pictures for those who come behind us to know the truth.

When you consider the impact that Da Vinci’s wrong picture has had in etching our picture of Jesus, intentionally or not, you can realize the seriousness of taking things out of context. Along with this, due to the innumerable “restorations” and re-paintings of Da Vinci’s work over 500 years, we cannot even be sure that what we see today is what he actually painted.

This scenario has been a great example of what we must not do with scripture. As we are learning and studying we should always be careful to keep things in their historical and cultural context. So as we listen, and dig, and teach, and paint, let us pray for much wisdom so that all those whom we disciple will hear a story, and see a picture that is bright, and clear, and true.

~~~~

1 Dwight A. Pryor, “Misconceptions about Jesus and the Passover” Series by the Center for Judaic-Christian Studies, Dayton, Ohio jcstudies.com

2 Diane Stanley, Leonardo Da Vinci, William Morrow & Company, New York, 1996

3 Francesca Romei, Leonardo Da Vinci, Peter Bedrick Books, New York, 1994

4 Diane Stanley, ibid

5 Liana Bortolon, The Life & Times of Leonardo, The Curtis Publishing Company, New York, 1997

Photos: Leonardo da Vinci [Public domain], Joyofmuseums [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], BB [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

What’s the Good News?

by Lois Tverberg

How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news, who proclaim peace, who bring good tidings, who proclaim salvation, who say to Zion, “Your God reigns!” (Isaiah 52:7)

Some kinds of news have the power to change our lives overnight — the birth of a baby, the diagnosis of cancer, the closing of a factory. The news of the end of a war or toppling of an evil government can mean new life for millions. We remember with great joy the end of World War II, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and even the toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein. People who had lived in fear of torture and murder for decades said that they felt like they had been “reborn.” It was as if a nightmare was suddenly over and a new day had come.

Interestingly, the Hebrew word besorah, which we translate to “good news,” has exactly that connotation. It is news of national importance: a victory in war, or the rise of a powerful new king. The word was used in relation to the end of the exile (Isaiah 52:7) and the coming of the messianic King (Isaiah 60:1). Often it is news that means enormous life change for the hearer.

Interestingly, the Hebrew word besorah, which we translate to “good news,” has exactly that connotation. It is news of national importance: a victory in war, or the rise of a powerful new king. The word was used in relation to the end of the exile (Isaiah 52:7) and the coming of the messianic King (Isaiah 60:1). Often it is news that means enormous life change for the hearer.

In Greek, there is an equivalent word, euaggelion, which we also translate as “good news, glad tidings, or gospel.” It also describes historic news of national importance. One place where this term is used is in the story of the angels who bring the news about the birth of Christ:

But the angel said to them, “Do not be afraid. I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is Christ the Lord. (Luke 2:10-11)

This announcement has a fascinating context. In Jesus’ time, there was a yearly announcement of the birthday of Caesar as “the euaggelion to the whole world.” The Roman Empire considered it great news to remind people of the ascendancy of this king and his reign over the known world. In the light of this, we see that the angels were doing the same thing, but in a much greater way — making an official proclamation to the all the nations about the birth of the true King of Kings, and the arrival of a new kingdom on earth.

When we learn that the word “evangelize” comes from euaggelizo (related to euaggelion), we can see the true power of the “good news” of the coming of Christ. Victory has been won in the war against Satan; and Christ, the true King, has come into power. This new King has come to extend an invitation to enter his kingdom and live under his reign. Like any regime change, the word “good” is far too bland to express the impact of this news that brings eternal life to its hearers. May the news of this King spread everywhere on earth!

~~~~

This article is an excerpt from Listening to the Language of the Bible, available in the En-Gedi bookstore.

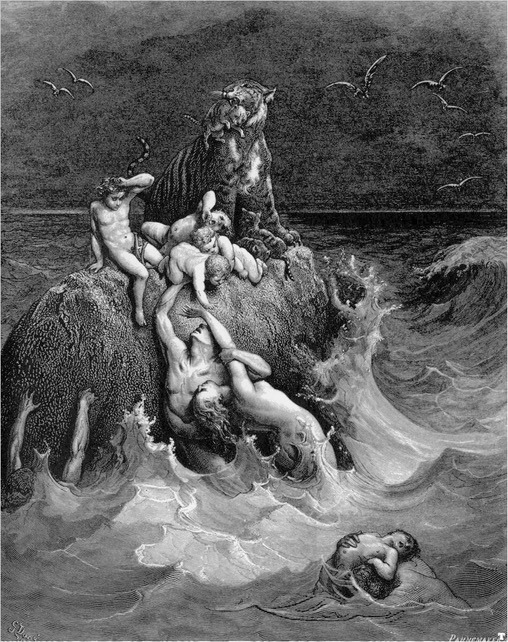

The Flood’s Deeper Message of Mercy

by Lois Tverberg

Most of us see Noah and the flood and as a story for children. We may think of wallpaper for the baby’s room with cartoons of cute animals, arks and rainbows. Others focus on its historicity — how the large the ark was, where it landed, or what geological features might remain.

These traditional ways of looking at the flood story miss its deeper significance, and reflect the difficulty Western Christians have with the Eastern way of communicating theological truth. The Bible’s writers saw theology in history, and composed their stories with an eye toward the meaning behind the events.

Most of us tend to simply read for historical details and miss the greater implications of Old Testament stories, thinking that we can only find theology in the New Testament. Surprisingly, if we look at the flood again, we find that this ancient narrative gives a profound answer to the difficult question of how a good God can tolerate sin.1

The Story of Sin in Genesis

When we read the story of the Fall, we don’t have much problem seeing the theological implications when Eve chooses to overrule God to eat from the tree. We understand what it says about rebellion and sin, and how they separate us from God. We often overlook that fact that the problem of sin is actually an important theme of several early chapters in Genesis, and culminates in the story of the flood.

Almost immediately after the fall, we read about Cain’s murder of Abel. It is ironic that these two were the first brothers ever born, representatives of all of us as children of Adam and Eve, but when one ignored the fact that he was his “brother’s keeper,” he destroyed him.2

From Eve’s small act of rebellion by eating the apple, sin grew until it led to murder, claiming the life of one of her children. Later in that same chapter, sin grew even worse, when Cain’s descendant, Lamech, bragged to his family that as violent as Cain was, he was much worse! He said,

For I have killed a man for wounding me; and a boy for striking me; If Cain is avenged sevenfold, then Lamech seventy-sevenfold!”3 (Genesis 4:24)

The words of Lamech show that sin doesn’t stop at murder. He went even beyond, claiming the right to kill for the smallest of offenses. With that kind of attitude, we aren’t surprised that in the very next generation, sin had reached its climax and provoked a response from God:

“Then the LORD saw that the wickedness of man was great on the earth, and that every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. The LORD was sorry that He had made man on the earth, and He was grieved in His heart. The earth was corrupt in the sight of God, and the earth was filled with violence (hamas).”4 (Genesis 6:5-6, 11)

In these first chapters of Genesis we can see that over just a few generations sin had infected humanity so completely that it grieved the heart of God. It was a theological statement about the wickedness of mankind, contrasted with the goodness of God who had a short time before declared his creation “very good.”

We might wonder what human beings could do that would cause God such grief, but if we remember the horrors the Nazis committed in concentration camps, or the deaths of thousands in torture chambers in Iraq, or the mass graves found in many places in the world, we understand. Humans really are capable of wickedness beyond the limits of the imagination.

The Theological Problem

How can a good and sovereign God tolerate sin? This is a classic question, debated for millennia. Some say that evil shows God is either not powerful or not good by giving the following argument:

1. A good God would destroy evil.

2. An all powerful God could destroy evil.

3. Evil is not destroyed.

4.Therefore, there cannot possibly be a good and powerful God.

It is interesting that we usually pass by a profound answer to this difficult question that comes only a few chapters after the Bible’s beginning.

The flood does show that the first proposition is true: A good God would destroy evil. In the flood epic, we see a righteous God’s response to the depth of human wickedness. We usually miss the fact that the deluge was the most horrific act of judgment that the world had ever seen!

Rather than being a cute children’s story, the horror of the flood was captured in a woodcut by Gustave Dore that shows storm waves crashing around a rock where a man and woman are clinging, trying to save the lives of their children. It truly was an event that would have been utterly shocking to our sensibilities, a scene of incredible devastation.5

So philosophers are right that a good God would act to end evil on earth. The problem is in the second thesis, that an all powerful God could destroy evil. The flood proved that no amount of destruction of human life will destroy evil. Evil is part of man’s basic inclination now, and to eliminate it, God would be forced to destroy mankind itself. Our earth today is still filled with violence: we are no different than the generation that made God regret he had made us. Surprisingly, God now has a different response:

“Never again will I curse the ground because of man, even though every inclination of his heart is evil from childhood. And never again will I destroy all living creatures, as I have done.” (Genesis 8:21)

It is hard to see what had changed after the flood, because the evil within man didn’t change. Instead, God vowed to restrain himself against universal judgment, even if it is deserved. For much of the next passage, God established laws against the bloodshed that filled the earth, and declared that life is precious, especially that of humanity. Humans are unique because we are made in the image of God. Could this be why God decided not to send another flood? Is it that in spite of our sinfulness, by bearing his image, we are still precious in his sight?

The Covenant of the Bow

In light of this, the sign of the rainbow has a profound message for us. The Hebrew word for “rainbow,” keshet, is used for “bow” throughout the rest of Scripture. It was the weapon of battle. The covenantal sign of the rainbow says that God has laid down his “bow,” his weapon; and he has promised not to repeat the judgment of the flood, even if mankind does not change. It is because people are so precious to him that he has constrained himself to finding an answer to the problem of sin other than the obvious one of universal judgment.

In light of this, the sign of the rainbow has a profound message for us. The Hebrew word for “rainbow,” keshet, is used for “bow” throughout the rest of Scripture. It was the weapon of battle. The covenantal sign of the rainbow says that God has laid down his “bow,” his weapon; and he has promised not to repeat the judgment of the flood, even if mankind does not change. It is because people are so precious to him that he has constrained himself to finding an answer to the problem of sin other than the obvious one of universal judgment.

Throughout the rest of the Bible, whenever God made a covenant, it was of monumental importance in his plan for the salvation of the world. The covenants with Abraham, with Israel on Mt. Sinai, and with King David to send the Messiah were all key events in salvation history.

We should realize that the covenant with Noah is just as important, because in it he promises to find another way to deal with the problem of sin than just to destroy sinners. It is the most basic covenant of all: to promise to find a way to redeem humanity from evil rather than just to judge it for its sin.

We know that Jesus promised to return to judge, so the day of reckoning is coming, but God sent Christ so that as many as possible could find his atonement before that time, so that God could show as much mercy as possible to the earth. His slowness to judge is not out of impotence, but out of his great mercy. As Peter says,

Long ago by God’s word the heavens existed and the earth was formed out of water and by water. By these waters also the world of that time was deluged and destroyed. By the same word the present heavens and earth are reserved for fire, being kept for the day of judgment and destruction of ungodly men. But do not forget this one thing, dear friends: With the Lord a day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years are like a day. The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. He is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance. (2 Peter 3:4-9)

Now we have a different way of looking at that classic debate, perhaps the way God sees it:

1. God is good and is able destroy all evil.

2. But in doing so, he would destroy humanity, which is precious to Him.

3. Evil is not destroyed.

4. God is infinitely good and powerful, but out of mercy, chooses to wait to judge. In response to sin, he sent his Son as an atonement for all who would receive him.

Even in this story at the very beginning of the Bible, we can see God’s ultimate desire for mercy rather than punishment for sin. He will finally bring it to maturity in Christ, who will extend a permanent covenant of peace with God through his atoning blood.

~~~~

1 See also Listening to the Language of the Bible, pp 51-52, available in the En-Gedi bookstore.

2 Ibid, pp 77-78.

3 Jesus may have been referring to Lamech in his teachings on being the opposite — seeking forgiveness instead of revenge. See “Lamech’s Opposite.“

4 It says something that the terrorist organization Hamas chose to name itself for the Hebrew word for “violence,” hamas, the very thing that grieved God’s heart so much that he regretted making humanity.

5 In September 2001, our Bible study was discussing the story of Noah. Our first response was why God didn’t just destroy the terrorists of 9/11 before they acted. From this story, we realized that no amount of destruction of evil human beings would rid us of the problem of evil in mankind.

Photos: Simon de Myle [Public domain], Gustave Doré [Public domain], Yulia Gadalina on Unsplash

Acts of Loving Kindness at Christmas

by Lois Tverberg

Many of us struggle with Christmas. It doesn’t really feel right to hunt for yet another expensive toy to give to already spoiled kids (or adults) on our list. Some have decided not to celebrate the holiday at all, because of the non-biblical traditions that are a part of it. Yet God redeemed us Gentiles from our pagan roots, and his gracious policy over the ages has been to transform rather than to cast aside.1 Instead of throwing out Christmas, perhaps we should ask how we can make our celebrations of the coming of our Messiah truly reflective of his love.

Many of us struggle with Christmas. It doesn’t really feel right to hunt for yet another expensive toy to give to already spoiled kids (or adults) on our list. Some have decided not to celebrate the holiday at all, because of the non-biblical traditions that are a part of it. Yet God redeemed us Gentiles from our pagan roots, and his gracious policy over the ages has been to transform rather than to cast aside.1 Instead of throwing out Christmas, perhaps we should ask how we can make our celebrations of the coming of our Messiah truly reflective of his love.

How can we bring more glory to Messiah Jesus at this time of year? Jesus’ Jewish culture asked a related question from the following verse:

The LORD is my strength and my song; he has become my salvation. He is my God, and I will praise him, my father’s God, and I will exalt him. (Exodus 15:2)

From this line, rabbinic thinkers saw the words “I will exalt him,” and asked the question, “How can mere mortals hope to exalt God, the Creator of the entire universe?” In the same way we could ask, how can we bring more glory to someone as infinitely wonderful as God’s own son, the Christ?

Beautifying His Commands

The rabbis had a wonderful answer. They said humans can bring more glory to God, who had all the glory in the heavens, by doing his will on earth in the absolute best and beautiful way possible. They called this hiddur mitzvah, meaning to beautify God’s commands. In the same way, we can do what Jesus commands in the absolute best way possible.

Christians may be surprised that the word mitzvah, meaning “command” or “commandment,” is positive rather than negative in Jewish culture. The word is found in many verses, like the following: “Keep my commands (mitzvot, pl.) and follow them. I am the LORD” (Lev. 22:31).

We tend to assume it refers to burdensome regulations, but the usual Jewish usage of mitzvah is that it is an opportunity to do something good God told you to do. People say things like, “I had a chance to do a mitzvah today when the elderly woman asked for my help.” The word is always used in a positive way, suggesting that doing what God has asked is a joy and a spiritual opportunity, not a burden.2

The idea of hiddur mitzvah (beautifying the command) goes even beyond this — that if God tells us to do something, we shouldn’t just do the minimum, but to perform it in the best way possible, sparing no expense or trouble. When one poor Jewish man was asked why he spent $50 for a citron, a lemon-like fruit required for the Feast of Sukkot, he replied, “Why would we worship God with anything less than the very best?” Using our resources sacrificially to do God’s will is a way of showing great love for God.

We can also see Jesus describing this behavior of hiddur mitzvah, going far beyond the minimum, in his story about the Good Samaritan. The Samaritan man obeyed God’s command to love his neighbor by personally caring for the wounded traveler, carrying him to the inn on his own donkey, and investing a large sum of his own money to care for him. As a Samaritan in Israel he even risked his own life, because as an enemy of the Jews, he could have been accused of being the attacker (Luke 10:33-35).

Good Works?

Christians from some traditions may worry about doing “works” — good things for others — thinking that it is a way of denying that we are saved by grace. It’s very important to remember that we are redeemed by faith in Christ, not because we’ve earned it. We can learn the correct attitude from Paul’s statement about works:

Christians from some traditions may worry about doing “works” — good things for others — thinking that it is a way of denying that we are saved by grace. It’s very important to remember that we are redeemed by faith in Christ, not because we’ve earned it. We can learn the correct attitude from Paul’s statement about works:

For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith – and this not from yourselves, it is the gift of God – not by works, so that no one can boast. For we are God’s workmanship, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do. (Eph. 2:8-10)

Paul says that salvation does not come from earning it through works, but it is a free gift from God through faith in the one he has sent. Surprisingly, though, the very next thing he says is that doing good works is the very purpose for which we were created! It is not that obeying God is the way we earn his love; rather it is that God, out of love, created us to serve him this way in the first place. Paul says something very similar to the rabbis:

For three things the world is sustained: For the study of scriptures (torah), for worshipping and serving God (avodah), and for deeds of lovingkindness (gemilut hesed).3

What this means is that for three great reasons God created humanity and allows the world to even keep existing: for humans to discover God’s great love through his Word; to worship him and want to serve him because of it; and then to show God’s love to those around us. Paul also says that we were created for this purpose, to bring God glory by doing loving acts that he even planned ahead of time. All of this comes back to the first question: how can humans increase God’s (and therefore Christ’s) glory? By glorifying God by reflecting his love.

Gemilut Hesed

One of the most beautiful concepts from Jesus’ culture is that of gemilut hesed (gem-i-LOOT HES-ed), acts of lovingkindness. In Jesus’ time, attention was given to giving money to the poor, and Jesus himself emphasized it.

As good as it was to give to the poor, gemilut hesed was considered even better. It is easy to hand a $10 bill to a poor man to give him money for a meal, but to invite him into your home and share a meal shows God’s love, and causes you to grow in love as well. Because of this, some Jews make a point to use some of their “giving dollars” to do gemilut hesed with their own hands.4 I know of a woman in Jerusalem who loved to read, so she invested in a library of books and then regularly found ways of loaning or even giving them to others. Certainly a Christian could do even more by buying and sharing good devotional books or Bible studies with others.

Considering how much money we spend on entertainment from movies, cable TV, etc, wouldn’t a wonderful Christian alternative be to “entertain” ourselves with gemilut hesed? To make a “hobby” out of a particular form of kindness to others? One Christian couple I know invested in a truck to use during snowstorms, to go up and down their country road pulling people out who had slid off the road. Another friend makes a habit of stopping to help or offer a cell phone to anyone stranded with road trouble. Yet another woman, who teaches classes on job hunting, enjoys helping friends find jobs if they need one or want one that suits them better.

What about making a practice of being kind to waitresses and tipping them generously? Or inviting single or elderly people home for Sunday dinner after church? As well as, of course, to share your faith in Christ? All these kind acts have the effect of showing God’s love to others in small and great ways. They likely will have an even bigger impact on ourselves and our families, as we see God’s love transform our hearts in the process.

What about making a practice of being kind to waitresses and tipping them generously? Or inviting single or elderly people home for Sunday dinner after church? As well as, of course, to share your faith in Christ? All these kind acts have the effect of showing God’s love to others in small and great ways. They likely will have an even bigger impact on ourselves and our families, as we see God’s love transform our hearts in the process.

During Christmas time, we celebrate God’s loving act of gemilut chesed, of coming to dwell among his people on earth. He went far beyond the minimum to display his love by healing the sick, feeding the hungry, and showing mercy to the leper and outcast, and finally by dying to save his people from their sins. What better way to celebrate his coming than to spare no expense to obey his commands in the best possible way, in order to show his tremendous love to the world.

~~~~

1 For some thoughts on what God might think about using pagan traditions like Christmas trees to worship him, see “Of Standing Stones and Christmas Trees.”

2 For an example of the positive Jewish attitude toward God’s commands (mitzvot), see “Mastering One Mitzvah,” from aish.com.

3 Verse 1:2 of Pirke Avot, (Sayings of the Fathers), a collection of rabbinic sayings written about 200 AD in the Mishnah. Many of these saying were attributed to rabbis who lived in Jesus’ time and even before, and many relate to things Jesus said as well. This saying is attributed to Simon the Righteous, who was said to live at the time of Ezra.

4 For many wonderful stories of the practice of Gemilut Hesed, see the outstanding book, The Book of Jewish Values, by Joseph Telushkin, (c) 2000, Bell Tower, New York

Photos: freestocks.org on Unsplash, Tom Parsons on Unsplash, Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

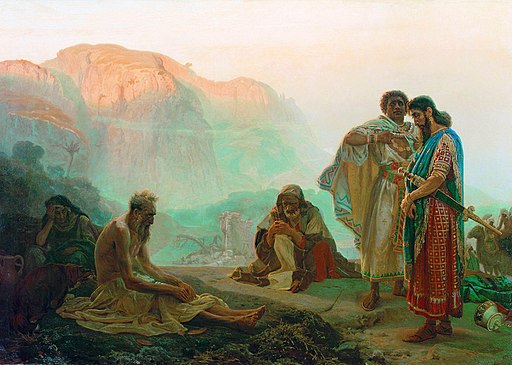

The Tsunami: Thoughts from Job and Jesus

by Lois Tverberg

When the tragic tsunami took the lives of over 200,000 people in Indonesia and other countries back in 2004, many were horrified by the suffering of so many people, and struggled with hard questions for God. Others discussed why it happened at that place and time, and wondered if it was an act of judgment from God. What would Jesus have said? Or Job? Let’s look at how these two key figures who were so acquainted with suffering would have seen the tragedies of today.

Wisdom from the Story of Job

It is interesting how the discussion around the tsunami resembled the debate between Job and his friends, Bildad, Eliphaz and Zophar. Job, of course, was a pious man who suffered for no reason he could find. His friends, however, asserted that God is all powerful, perfectly just, and knows every person’s sins, so therefore Job somehow had to have deserved his trials. Their logic seems flawless. Nonetheless, Job maintained his innocence and had very angry words for God about his lack of justice as he saw it. He bluntly said:

[God] stands alone, and who can oppose him? He does whatever he pleases… Why does the Almighty not set times for judgment? Why must those who know him look in vain for such days? Men move boundary stones; they pasture flocks they have stolen. They drive away the orphan’s donkey and take the widow’s ox in pledge. The fatherless child is snatched from the breast; the infant of the poor is seized for a debt.The groans of the dying rise from the city, and the souls of the wounded cry out for help. But God charges no one with wrongdoing. (Job 23:13; 24:1-3, 9, 12)

In the light of this harsh accusation, Job’s friends defended God, and said to Job:

“Far be it from God to do evil, from the Almighty to do wrong. He repays a man for what he has done; he brings upon him what his conduct deserves. It is unthinkable that God would do wrong, that the Almighty would pervert justice…Will you condemn the just and mighty One?” (Job 34:10-14, 17)

Truthfully, we must admit that Job’s friends have a very good point, and are trying to honor God. They echo many proverbs that say God rewards the actions of the righteous and punishes the wicked. If we didn’t know the rest of the story, we may even take their side.

God’s Surprising Response

It is fascinating to read God’s concluding words of the debate, because after all Job’s criticism, and the men’s strong defense of God’s honor, God was furious with Job’s friends! God said to Eliphaz,

“I am angry with you and your two friends, because you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has.” (Job 42:7)

It seems that God considered Job’s words that were spoken in anger at him to be truthful, while the other men’s theories defending his ways as untruthful. How could that be? We know that neither Job nor his friends knew God’s real reasons for allowing Job’s trials.

It wasn’t just that they didn’t know about Satan’s challenge, but that as finite humans, God’s eternal plan was utterly beyond them. God didn’t answer Job’s questions about evil because no human can grasp his unfathomable purposes. In spite of their ignorance, Job’s friends had the gall to presume to understand and speak for God, and accuse Job of sin. It should humble us when we want to put words in God’s mouth: how can we know for sure what he would say?

It is also interesting that God says that Job “has spoken what is right,” after Job’s accusations about God’s injustice toward the poor. When Job protested against their suffering, he actually was expressing the same compassion for the needy that God himself has. In contrast, Bildad, Eliphaz and Zophar’s theology had little concept of God’s love, so it was a misrepresentation of God’s heart.

While neither Job or his friends knew God’s future plans for redemption, Job at least understood God’s care for the suffering. Perhaps God would rather hear us ask angry questions that show concern for other’s pain, than for us to look for correct answers but not have love.

Our Christian culture tends to focus on theology concerning such things as the trinity, atonement, or free will vs. predestination, etc. Jewish culture over the millennia has tended to avoid this type of discussion because of the danger of the sin Job’s friends: claiming to have more knowledge of an infinite, mysterious God than we can possibly have. Since we are small and finite, we give God more honor by trying to love as he loves than to try to know all that he knows.

The Same Difficult Question in Jesus’ Age

The question of suffering came up often in Jesus’ time too, because he lived at a unique point in Jewish history. The people were greatly oppressed under Roman and Herodian rule, with extreme taxation and barbaric cruelty. Along with Jesus, thousands of other Jews were crucified by the Romans. Even before the Romans took power, the Greek Seleucids persecuted and executed any Jew who studied the Scriptures or circumcised their sons. Indeed, the suffering of the Jews before and during Jesus’ time was unmatched in their history until the Holocaust.1

This gave rise to an enormous theological problem that was reminiscent of Job’s situation: in the Old Testament, it was understood that when Israel suffered, it was because of its sins against God. The covenant at Sinai had been sealed with promises of blessings for obedience and curses for disobedience (Lev. 23, Deut. 28-29).

In Jesus’ time, for the first time in their history, they were being persecuted for their loyalty to God, and the most faithful people suffered most. Jesus responded at one point to this when he said:

Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you who hunger now, for you shall be satisfied. Blessed are you who weep now, for you shall laugh. Blessed are you when men hate you, and ostracize you, and insult you, and scorn your name as evil, for the sake of the Son of Man… But woe to you who are rich, for you are receiving your comfort in full. Woe to you who are well-fed now, for you shall be hungry. Woe to you who laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep… (Luke 6:20-26)

When we first read Jesus’ words, they seem too harsh. Why would Jesus proclaim that anyone who has enough to eat will go hungry? Or why would he want those who are happy to weep instead? Jesus was repeating many of the blessings and woes of Deut. 28, but instead of describing this life, he was saying that God’s reward will come later to many who did not feel his blessing here.

Indeed, those who were most faithful in trials will be rewarded most greatly. We cannot look at a persons’ earthly blessings and say that we know how much God approves of our lives. To the contrary, those of us who are comfortable should examine ourselves to see if we the ones who Jesus is speaking against.

Were The Galileans Worse Sinners?

A discussion very close to that about whether the tsunami was God’s judgment came up in Jesus’ life, when some Jews were murdered by Pilate:

Now there were some present at that time who told Jesus about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mixed with their sacrifices. Jesus answered, “Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans because they suffered this way? I tell you, no! But unless you repent, you too will all perish. Or those eighteen who died when the tower in Siloam fell on them – do you think they were more guilty than all the others living in Jerusalem? I tell you, no! But unless you repent, you too will all perish.” (Luke 13:1-5)

Once again, people were asking Jesus whether misfortune showed that God was punishing sin, and Jesus said this was not true. Instead, he reminded them that true judgment will come some day, but this age is a time of grace, when God is seeking out sinners and calling them to repent. Rather than feeling secure if we are prospering because we think we have God’s approval, Jesus says that we should examine ourselves, because soon it will be too late.

Looking at the Tsunami

As we study these examples from Job and from Jesus’ own words, we can see that questions like, “Why did God send a tsunami?” aren’t ones that God will answer to our satisfaction. God showed Job that the answers were utterly beyond him by challenging him to be a god himself — no human could hope to understand God’s ways.

When Jesus was here, he reminded us that misfortune here is not God’s judgment because in this life we are under his mercy. We should therefore examine ourselves now and come to him for forgiveness, because judgment will come in the end.

Whenever we see innocent people suffering, we can at least remind ourselves that while they would not have chosen their fate, God willingly came in the person of Christ to suffer as an innocent person out of his desire to forgive his people’s sins. That should always remind us of his empathy for suffering and his goodness, in which we can always put our trust, even if we don’t know all of his thoughts.

~~~~

Photos: Ilya Repin [Public domain], Brooklyn Museum [Public domain],

Who Are You Going to Work For?

by Lois Tverberg

Freedom is the theme of God’s greatest miracles in history. Jews look back on the freeing of Israel from bondage in Egypt as their foundation as a people. They still celebrate this yearly at Passover, when they commemorate the night they were liberated. Christians recall Jesus’ death and resurrection as an act that brought far greater freedom for all people who believe in him, from bondage to sin and death itself.

Freedom is the theme of God’s greatest miracles in history. Jews look back on the freeing of Israel from bondage in Egypt as their foundation as a people. They still celebrate this yearly at Passover, when they commemorate the night they were liberated. Christians recall Jesus’ death and resurrection as an act that brought far greater freedom for all people who believe in him, from bondage to sin and death itself.

In light of these two great acts of liberation from bondage, we may be uncomfortable with the fact that instead of speaking only of freedom, Jesus and Paul often speak about being “slaves” to God or Christ. Jesus says that “You cannot serve two masters, God and money” (Matt 6:24), and Paul says, “You were bought at a price” (1 Cor. 6:19 & 7:23). Paul and other New Testament authors also introduce themselves at the beginning of each book as being “slaves of Christ.”1

It seems paradoxical to speak about slavery and being set free simultaneously, but if we look back and understand God’s first redemption of Israel, we will see how this really is a theme from the beginning of the scriptures to the end. God set his people free from cruel masters to become his own, as their rightful Lord. Both at the first exodus and in Christ’s fulfillment, this picture teaches us much about what our relationship to God really is.

Set Free from Cruel Masters

The common belief of people in the ancient near east was that the world is filled with many spiritual beings that control nature and prosperity. These “gods” were unpredictable and cruel, and used humans as playthings and slaves to serve their own desires.2 Ancient people understood that all people were the slaves of the gods, and each tribe had its own gods that ruled over them, so that to survive, they had to appease the gods through religious ceremonies and magical incantations.

Because of these beliefs, many ancient writings reflect a perpetual sense of hopelessness, anxiety and fear of the spirit world that was hostile to humanity. Interestingly, this pessimistic worldview of polytheism is widespread, from ancient times even up to today.3

Knowing this helps us read the story of the redemption of Egypt as an ancient person would have understood it. They saw this story as a true spiritual battle between the God of Israel and the gods of the Egyptians. Not only were the Israelites in bondage to physical slavery, they were in bondage to these evil gods, including Pharaoh, who considered himself a god.

Knowing this helps us read the story of the redemption of Egypt as an ancient person would have understood it. They saw this story as a true spiritual battle between the God of Israel and the gods of the Egyptians. Not only were the Israelites in bondage to physical slavery, they were in bondage to these evil gods, including Pharaoh, who considered himself a god.

Each plague was directed at a specific god of the Egyptians: Hekt, the frog god; Hapi, the Nile god; Ra, the sun god, etc., and the final plague was against Pharaoh himself (Ex. 12:12). The imagery here is that as God fought and defeated each one, God was winning a battle to take his own people out of the hands of other “gods” so that he would be their God, and they would become his people — his “slaves” as it were (Ex. 6:7, 2 Sam. 7:23).

A key to understanding this is to look at the Hebrew word for “worship,” avad, which has parallels in other languages of the near east. Along with meaning “worship,” it also means “serve” or “work,” and the related noun, eved, means “servant” or “slave.” So, the “worshippers,” avadim, of a god could also be seen as the god’s servants or slaves.

When God challenged Pharaoh, “Let my people go so that they may avad me” (Ex. 8:1), this didn’t just mean so that they could worship him, but that they were to be freed from slavery to the false god Pharaoh, so that they could avad, serve and worship their rightful God.

God later commanded that his people should “worship,” avad, no other gods, which can also be translated to mean they should “serve” no other gods. They were set free from them to serve and worship the true God alone. Serving and worshipping may not seem related to us, but really, service is the truest expression of worship of a god.4

God’s Compassion on Mount Sinai

After Israel was freed from bondage, they arrived at Mount Sinai, where God gave him his laws that showed how he wanted them to avad, worship and serve him as his people. We hardly think to compare the laws of the Torah to other law codes of the time, but it is interesting to see how God’s rules show that their new “master” was vastly different from their old masters — he governed with great compassion, and cared about the needs of his people.

After Israel was freed from bondage, they arrived at Mount Sinai, where God gave him his laws that showed how he wanted them to avad, worship and serve him as his people. We hardly think to compare the laws of the Torah to other law codes of the time, but it is interesting to see how God’s rules show that their new “master” was vastly different from their old masters — he governed with great compassion, and cared about the needs of his people.

We modern-day readers hardly appreciate the profound ethical change that the laws of the Torah made relative to other codes of its time, and how fundamental its precepts are to our own laws.5

Other codes had no ethic of equal treatment in regard to rich and poor, so a crime against a person of a high class carried a much greater punishment than one against a low class person. Cheating in a business transaction with a high class person carried the death penalty. In contrast, murder of a lower class person was punishable by a fine based on his social status. In Israel, all were alike under the law, and poor and rich treated equally.

In cases of crime, the Torah was far more humane. In other countries, punishments for even minor crimes were often brutal and mutilating, and often including floggings, amputation and torture. In the Torah, fines were common but physical punishments were rare, and only for severe offenses against the nation or God.

The law that sounds most shocking, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” is actually misunderstood. The expression was actually an idiom that wasn’t taken literally, but actually meant equitable punishment that fits the crime. (An eye for an eye — not a scolding for an eye, or a life for an eye.) It was an ancient expression from laws originally meant to limit punishment for an injury to no more than the injury itself, because without it, the victim’s clan would want greater vengeance, escalating into feuds. Scholars believe that it was not followed literally in Israel, but monetary fines were given for injuries instead.

In other codes, very little protection was given to those who were vulnerable to exploitation. The main goal of other law codes was to protect the assets of the wealthy from the lower class by threatening them with punishment for theft or destruction of property. Israel’s laws were instead very concerned for the protection of the poor, the alien, the widows and orphans.

People were to tithe their money to give to the poor, and let them glean from their crops (Deut. 18:29, Lev. 23:22). They were not to mistreat an alien, but to “love them as themselves” (Lev. 19:34). Much of the code of Israel is specifically written to protect the weakest members of the society, unlike any other nation of the time.6

With these differences in mind, the laws of the Torah show great fairness toward all levels of society, compassion for the vulnerable, and amazing concern for the sanctity of human life. Our own culture has been so transformed by these basic principles that we can hardly imagine the world without them.

The more we see the contrast between God’s ways and the rest of the ancient world, the more we see that the love of Christ in the gospels was fully present in the God who revealed himself on Sinai. In essence, we see the Father and Son as one and the same. The God who Israel was to avad, worship, cared deeply for humanity, and his servants were to mirror his concern as well.