by Lois Tverberg

It is always fascinating and enriching to bring the Hebraic cultural context into understanding the most important, basic words that Christians use. One of the most important is the word “Christ.” What does it mean to call Jesus, “Jesus Christ”? Or, what implications does it have for us to say that Jesus is the “Christ”?

First of all, the word “Christ” comes from christos, a Greek word meaning “anointed.” It is the equivalent of the word moshiach, or “Messiah,” in Hebrew. So, to be the Christ, or Messiah, is to be “the anointed one of God.”

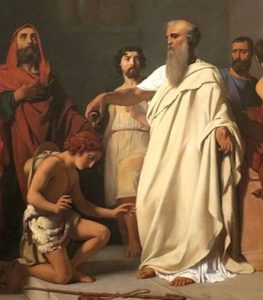

To be anointed is literally to have sacred anointing oil poured on one’s head because God has chosen the person for a special task. Priests and kings were anointed, and occasionally prophets. Kings were anointed during their coronation rather than receiving a crown.

To be anointed is literally to have sacred anointing oil poured on one’s head because God has chosen the person for a special task. Priests and kings were anointed, and occasionally prophets. Kings were anointed during their coronation rather than receiving a crown.

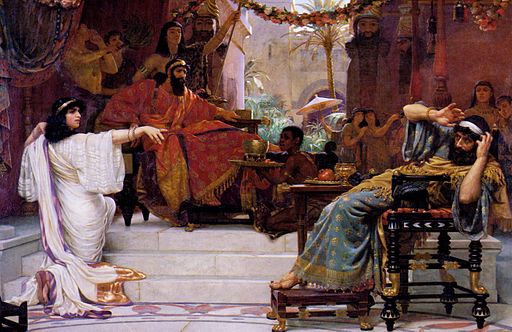

Even though prophets and priests were anointed, the phrase “anointed one” or “the Lord’s anointed” was most often used to refer to a king. For instance, David used it many times to refer to King Saul, even when Saul was trying to murder David and David was on the verge of killing Saul to defend himself:

Far be it from me because of the LORD that I should do this thing to my lord, the LORD’S anointed (moshiach), to stretch out my hand against him, since he is the LORD’S anointed (moshiach). (1 Sam. 24:6)

So, the main picture of the word “Messiah” or “Christ” as the “anointed one” was of a king chosen by God. While Jesus also has a priestly and a prophetic role, the main picture that word “Messiah” is used for is a king.

Through the Old Testament, we see little hints that God would send a great king to Israel who would someday rule the world. In Genesis, Jacob gives blessings to all of his sons, and of Judah he says,

The scepter will not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until he comes to whom it belongs and the obedience of the nations is his. (Gen. 49:10)

This is the first hint that they were expecting a great king to arise out of Israel who would be king over the whole earth. The clearest prophecy about this messianic king who was coming is from King David’s time. David told God that he wanted to build God a “house,” meaning a temple.

God said to him that instead his son Solomon would do that, and then promised that he will build a “house” for him, meaning that God will establish his family line after him. God further promises David that from his family will come a king whose kingdom will have no end:

“When your days are over and you go to be with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, one of your own sons, and I will establish his kingdom. He is the one who will build a house for me, and I will establish his throne forever. I will be his father, and he will be my son. I will never take my love away from him, as I took it away from your predecessor. I will set him over my house and my kingdom forever; his throne will be established forever.” (1 Chron. 17:11-14)

This prophecy has been understood as having a double fulfillment — it is first fulfilled in Solomon, who built the temple, but did what God forbade — amassed a great fortune and married foreign wives. His kingdom broke apart a few years after his death.

It also spoke about a “Son of David” who would come, who would have a kingdom without end. This prophecy is the seedbed of all of the messianic prophecies that talk about the “son of David” and the coming messianic king.

Jesus as the Christ

Even though we tend to not pick up on the cultural pictures, the gospels tell us many times that Jesus is this great King who has come. In Matthew 2, the wise men come to bring presents to this king whose star they have seen in the east. This was a fulfillment of Numbers 24:17, Isaiah 60, and Psalm 72.

Even though we tend to not pick up on the cultural pictures, the gospels tell us many times that Jesus is this great King who has come. In Matthew 2, the wise men come to bring presents to this king whose star they have seen in the east. This was a fulfillment of Numbers 24:17, Isaiah 60, and Psalm 72.

The latter two passages both describe the coming of a great king and describe how representatives from nations everywhere would come to give him tribute:

He will endure as long as the sun, as long as the moon, through all generations. … He will rule from sea to sea and from the River to the ends of the earth. The desert tribes will bow before him and his enemies will lick the dust. The kings of Tarshish and of distant shores will bring tribute to him; the kings of Sheba and Seba will present him gifts. All kings will bow down to him and all nations will serve him. (Ps. 72:5, 8-11)

Soon after Jesus begins his ministry he proclaims himself as the anointed one (the Christ) in Luke 4 when he says that passage from Isaiah 61 has been fulfilled:

The Spirit of the Sovereign LORD is on me,

because the LORD has anointed me

to preach good news to the poor.

He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted,

to proclaim freedom for the captives

and release from darkness for the prisoners,

to proclaim the year of the LORD’s favor. (Is 61:1-2)

This is a picture of the coming messianic King, right after he is anointed by God, declaring good news of the jubilee year, a tradition observed when a new king came into power in some middle eastern countries.1 Jesus applied it to himself, arousing a very strong reaction from his audience to his bold claims.

We see yet another picture of Jesus as King when he rode on the donkey into Jerusalem. This was very much a kingly image, often part of the annunciation of a new king, as it was for Solomon in 1 Kings 1:38-39. It is the fulfillment of Zechariah 9:9, the triumphal entry of the messianic king.

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion!

Shout, O daughter of Jerusalem!

Behold, your king is coming to you;

He is just and endowed with salvation,

Humble, and mounted on a donkey,

Even on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

During Jesus’ trial, the main question he is asked is “Are you the King of the Jews?” and he answers affirmatively:

And they began to accuse him, saying, “We found this man misleading our nation and forbidding to pay taxes to Caesar, and saying that he himself is Christ, a King.” So Pilate asked him, saying, “Are You the King of the Jews?” And he answered him and said, “It is as you say.” (Luke 23:2-3)

What are the implications of Jesus as King?

When we think about Jesus’ time on earth, the last thing we think of is of a king who is reigning, but Jesus explains that his kingdom is not of this world (John 18:37). Rather, Jesus is talking about the kingdom of God, the major focus of his preaching.

When we think about Jesus’ time on earth, the last thing we think of is of a king who is reigning, but Jesus explains that his kingdom is not of this world (John 18:37). Rather, Jesus is talking about the kingdom of God, the major focus of his preaching.

The kingdom of God is made up of those who submit their lives to God to reign over them. As the King that God has sent, and of course because he is God, the kingdom of God is Jesus’ kingdom. He speaks about how it is expanding like yeast or mustard seed, as the gospel that he has arrived goes forth and many more accept him as their King. When he returns in glory, all the earth at that time will see that he is King.

Did the people around him see him as a king? The fact that Jesus’ disciples and others who believed in him referred to him as “Lord” suggests that they were giving him great honor, with the understanding that he is the Messianic King.

Throughout the gospels Jesus is addressed with respect by strangers as “rabbi” or “teacher.” Only a few times is he actually addressed using his common name, Jesus, and only by demons (Mark 1:24) as well as a few who didn’t know him. To call Jesus “Lord” is using a term for addressing royalty, like saying “Your Majesty” or “Your Highness.” It is also a common term for addressing God himself, and has a hint of worshipping Jesus as God.

To use the word “Lord” displays an attitude of obedient submission to a greater power. Jesus seems even to expect that those who call him Lord obey him — he said to his listeners, “Why do you call Me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ and do not do what I say?” (Luke 6:46).

To call him “Lord” or to call him Jesus “Christ” is to say that he is the King that God has sent, who has a right to reign over us. It is interesting that even though the demons know that he is the Son of God, they refuse to use the word Lord to address him (Luke 4:34, 40)!

This has implications about the basic understanding of what a Christian is. We tend to define ourselves by our creeds and statements of belief, but the very word Christ calls us to more than that. If Christ means King, a Christian is one who considers Jesus his Lord and King, and submits to his reign. Those who are saved have two things: both a belief in the atoning work of Jesus, and a commitment to honor him as their personal Lord and King. As Paul says,

If you confess with your mouth Jesus as Lord, and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. (Rom. 10:9)

~~~~

1 See the En-Gedi article, “The Gospel as the Year of Jubilee.”

Photos: François-Léon Benouville [CC BY-SA 4.0], John Stephen Dwyer [CC BY-SA 3.0], Ikiwaner [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most important day of the year for Jews. It begins before sunset the night fore, and includes a 25 hour fast from both food and water, and ceasing of all work. It is a day set aside to “afflict the soul,” to ask for atonement for the sins of the past year. Even Jews who otherwise are not observant will observe this day.

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most important day of the year for Jews. It begins before sunset the night fore, and includes a 25 hour fast from both food and water, and ceasing of all work. It is a day set aside to “afflict the soul,” to ask for atonement for the sins of the past year. Even Jews who otherwise are not observant will observe this day.