by Lois Tverberg

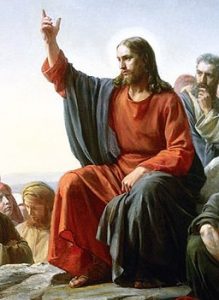

The Jews of Jesus’ day were longing for a messiah, but for many, Jesus didn’t meet their expectations. What were they looking for, from how they read their Scriptures? Understanding the issues at hand can shed much light on Jesus’ teachings, which often were addressing these expectations. By situating his message in its original context, we’ll see how radical it was, and more importantly, its implications for us as members of his kingdom.

The Expectations of the Ancient World

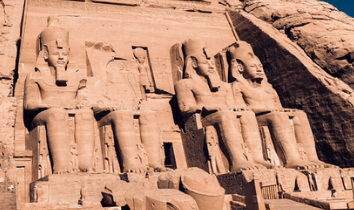

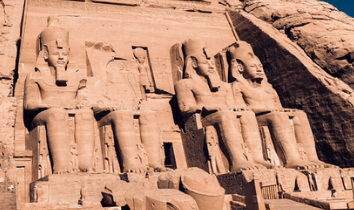

The ancient world thought very differently than modern Westerners do, and God chose to reveal himself and the Messiah in ways that they would understand. In the polytheistic ancient Near East, it was understood that each nation worshipped its own “god” or “gods,” and the prominence of each nation showed the power of its gods.  God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers.

God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers.

God’s ultimate goal, according to the prophets, was to expand his reign over all the world until one day no other gods were worshiped anywhere: “The LORD will be king over all the earth; in that day the LORD will be the only one, and His name the only one” (Zech 14:9).2 One Jewish prayer, the Alenu, which likely precedes the first century AD, expresses that hope this way:

“Therefore do we wait for Thee, O Lord our God, soon to behold Thy mighty glory, when Thou wilt remove the abominations from the earth, and idols shalt be exterminated; when the world shall be regenerated by the kingdom of the Almighty, and all the children of flesh invoke Thy name; when all the wicked of the earth shall be turned unto Thee.

Then shall all the inhabitants of the world perceive and confess that unto Thee every knee must bend, and every tongue be sworn. Before Thee, O Lord our God, shall they kneel and fall down, and unto Thy glorious name give honor.

So will they accept the yoke of Thy kingdom, and Thou shall be King over them speedily forever and aye. For Thine is the kingdom, and to all eternity Thou wilt reign in glory, as it is written in Thy Torah: ‘The Lord shall reign forever and aye.’ And it is also said: ‘And the Lord shall be King over all the earth; on that day the Lord shall be One and His name be One.'” 3

Notice how the focus on the coming of God’s kingdom in the Alenu echoes the Lord’s Prayer — that God would establish his kingdom on earth and that his glory be seen throughout the world.

Messiah as King of God’s Kingdom

Along with the idea that God would extend his kingdom over all the earth was the idea that God would send a great king to establish and reign over it, and therefore, the whole world. This great king of Israel, or “anointed one” (mashiach) is the Messiah, which is christos in Greek, or “Christ.” Many messianic passages describe him in just this way:

The scepter will not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until he comes to whom it belongs and the obedience of the nations is his. Genesis 49:10

The kings of the earth take their stand and the rulers gather together against the LORD and against his Anointed One (mashiach) … I will make the nations your inheritance, the ends of the earth your possession. Psalm 2: 2, 8

These prophecies describe an anointed King who rules over the whole world. Grasping this imagery of the Messiah should help us see the many messianic claims Jesus made during his ministry. In Luke 4, Jesus read the from Isaiah 61 in his hometown synagogue, “The Lord has anointed (“mashiach”ed) me…” and said that it had been fulfilled in their hearing. By doing so he was boldly claiming to be the Messiah. Also, whenever he spoke about the “kingdom of God” and referred to it as “my kingdom,” he was claiming the same thing.  When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4

When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4

The Messiah the People Expected: Warrior & Judge

How would God’s king establish his kingdom? One logical conclusion would be that the Messiah would wage war against the idol-worshiping Gentiles and destroy sinners among the Jews. You might be surprised at how many prophecies in their Scriptures sounded like they confirmed their ideas.

The Messiah was to be a “Son of David” (a descendant of King David), so people expected that just as David had expanded God’s kingdom by going to war, the messianic “Son of David” would too.

The Messiah was expected to be like Moses, who defeated the Egyptians and established Israel as a nation at Mt. Sinai.5 The idea that the Messianic king would lead a rebellion was a prominent expectation, which was why when Jesus admitted to being the Christ, he was accused of stirring up a rebellion against Rome (Luke 23:2-5). After he multiplied the loaves and fish, his audience became convinced that he was giving them “manna” as another prophet-leader like Moses. They responded by wanting to make him king (John 6:14-15) for just this reason.

Many prophecies also anticipate the “Day of the Lord” — a climactic battle between God and his enemies after which the nation of Israel would come into its full glory (Zeph. 1:14-15, Zech. 14:1-3). It should be noted that the “Day of the Lord” was also to be a day of great judgment on all the sinners of Israel:

“The Lord, whom you seek, will suddenly come to His temple; and the messenger of the covenant, in whom you delight, behold, He is coming,” says the LORD of hosts.

“Then I will draw near to you for judgment; and I will be a swift witness against the sorcerers and against the adulterers and against those who swear falsely, and against those who oppress the wage earner in his wages, the widow and the orphan, and those who turn aside the alien and do not fear Me,” says the LORD of hosts. (Mal 3:1, 5)

From these and other passages, people expected that the Messianic King would come to bring war and also to judge the people. This made sense because along with leading the army, one of the main roles of a king was to act as supreme judge in the land. (Ps. 72:1-4)

In the New Testament, we see John the Baptist echoing these sentiments as he warns his listeners that Christ was coming in wrath, to chop down every tree that didn’t bear fruit and burn up evildoers like chaff in unquenchable fire (Lk. 3:17).

The Essenes also combined the roles of the Messiah as warrior and judge into one, imagining that he would lead a great war between the “Sons of Light” (their pure community) and the “Sons of Darkness” – sinful Jews and enemy nations that worship other gods.

Another Kind of Messiah – Shepherd, Servant, Jubilee King

Even though the people found evidence for a warrior Messiah in their scriptures, other passages paint a very different picture. More than one passage describes a king who comes in peace to reign over the earth, rather than in war:

Behold, your king is coming to you; He is just and endowed with salvation, humble, and mounted on a donkey, even on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

I will take away the chariots from Ephraim and the war-horses from Jerusalem, and the battle bow will be broken. He will proclaim peace to the nations. His dominion will be from sea to sea, from the River to the ends of the earth. Zech. 9:9-10 (See also Isaiah 9:6-7)

This passage is familiar to us from the scene in Jesus’ life when he entered Jerusalem on a donkey. The fulfillment of this prophecy showed that he was not coming to wage war like so many believed.

Jesus also deliberately applied other passages to himself that explained his mission. He spoke of himself as the “shepherd,” a reference to many messianic passages about a shepherd-king who would re-gather the wandering tribe of Israel and give them a new heart of love and obedience to God (Deut. 30:3-6, Jer. 23:3, Ezek. 34:11). He also spoke about being the “anointed” who was announcing a year of Jubilee — freedom from debt, using debt as a metaphor for sin6 (Is. 61:1-3).

Finally and most importantly, he fulfilled Isaiah 53, which describes God’s “servant” who takes all of the sins of the people on himself, who suffers and dies for their sins to purchase their forgiveness. Jesus came to expand God’s kingdom throughout the world by announcing forgiveness to all who would repent, rather than judgment on sinners.

The Critical Difference Between these Ideas

People often assume that Jesus was rejected by his listeners because they wanted a “political” messiah, as opposed to a “spiritual” messiah. But the reason many did not accept Jesus was because they were looking for a Messiah to come with judgment on the enemies of God, and he came with an offer of forgiveness and peace instead. It wasn’t that they hadn’t read the scriptures, but rather that Jesus didn’t fit their reading.

They expected the kingdom of God to be established by killing everyone who wasn’t righteous. But instead, God would gain a kingdom of pure-hearted followers, not by destroying all the impure, but by purifying sinners and atoning for their sins himself. The Messiah would indeed come again someday in judgment, but for now he was extending an invitation of forgiveness to everyone who would take it.

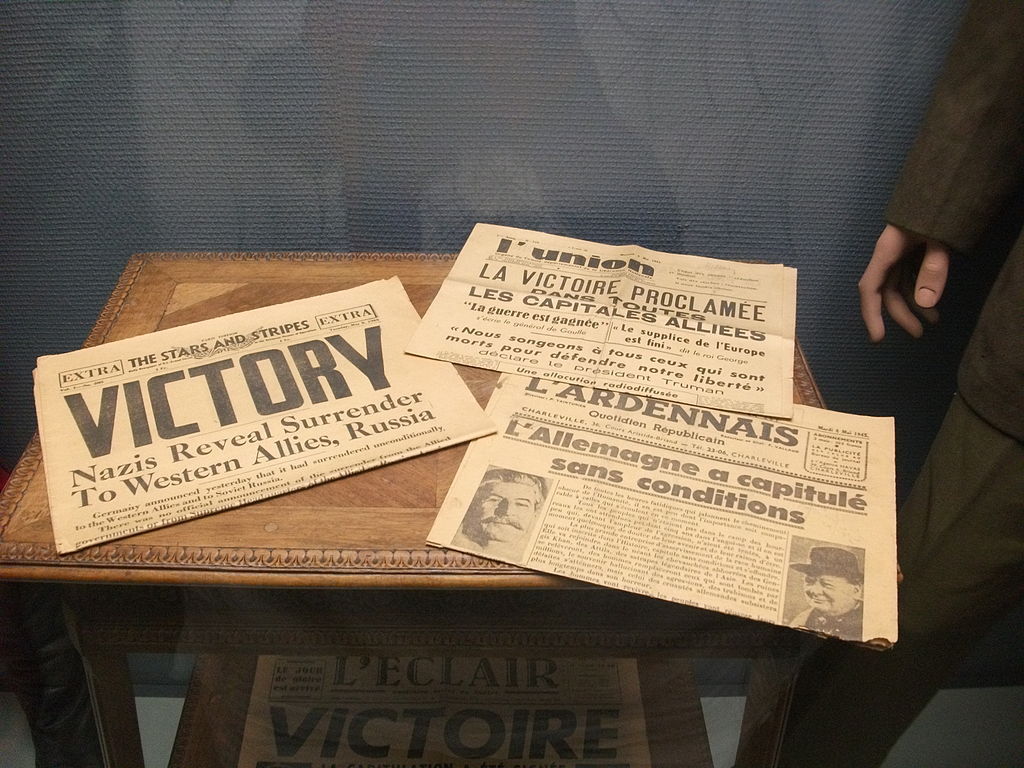

It is easy for us to condemn the people of Jesus’ time, but seeing more of the situation can give us empathy for them. The suffering of the Jews in Jesus’ day under the Roman Empire was as extreme as it was for those in Nazi Germany, according to historians. Torture and public crucifixion were commonplace, thousands were murdered, and taxes were overwhelming.

It is easy for us to condemn the people of Jesus’ time, but seeing more of the situation can give us empathy for them. The suffering of the Jews in Jesus’ day under the Roman Empire was as extreme as it was for those in Nazi Germany, according to historians. Torture and public crucifixion were commonplace, thousands were murdered, and taxes were overwhelming.

The Jews who were most faithful were persecuted most harshly, and only those who had “sold out” by serving the Romans prospered — the tax collectors and the corrupt Temple priests that colluded with them to exploit the faithful Jews.7

In their anguish, the Jews yearned for God to establish his kingdom of justice by purifying their nation from corruption and freeing it from their Roman persecutors. Even Jesus’ disciples were convinced that this was Jesus’ mission. After his resurrection they asked him “Lord, is it at this time You are restoring the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6). Jesus’ message was extremely difficult for his audience to hear — that only by letting go of vengeance could they enter God’s true kingdom.

The Challenge of the Kingdom

Ironically, the only people that would find a forgiving Messiah appealing were the “sinners” themselves. When prostitutes and tax collectors heard about a Messiah who didn’t bring judgment but rather forgiveness, it must have been the greatest news in the world to them.

The rest of his listeners must have felt just the opposite. As the innocent victims of Roman oppression, they saw themselves as the “righteous ones” who longed for vindication. They yearned for a Messiah who judged and defeated their enemies, rather than one who would forgive their sins but then demand that they forgive those who had wronged them.

The most profound thing about the “merciful kingdom” that Christ proclaimed was what it said about God. The ancient world believed that the gods of the nations battled against each other to expand their kingdom, but the true God came to suffer and die for the sins of his people instead. This God was a god of mercy and long-suffering love, who wanted sinners to be forgiven rather than being destroyed in judgment.

To truly grasp the kingdom message of our Messiah, we must be fully aware of our sinfulness and willing to ask for forgiveness, and to forgive those who have wronged us as well.

~~~~

1 When God sent the plagues to bring his people out of Egypt, for instance, each was targeted at an Egyptian god to show that God was supreme (Ex. 12:12). Many other Old Testament stories display God defeating false gods, like the fall of the Dagon idol before the ark (1 Sam 5:2) and the contest between Elijah and the Baal prophets (1 Ki 18:21).

2 Revelation also includes this imagery of the final climax to history when it says, “The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of His Christ (Anointed One); and He will reign forever and ever.” (Rev. 11:15)

3 The Alenu prayer is recited three times each day at the end of the synagogue service. Ironically, even though Jesus may have prayed this ancient prayer, it is now recited silently because Christians persecuted Jews who prayed it, thinking it was said against them. For more on its history, read jewishencyclopedia.com‘s entry on “Alenu.”

4 Other stories in Jesus’ life are included to show that he was the Messianic king. The visit of the Magi fulfilled the prophecies that kings of other nations would bring tribute to him (Is. 60, Ps. 72). The Holy Spirit descending on him at his baptism was reminiscent of how God’s spirit fell on anointed kings like Saul (1 Sam 10:10) and David (1 Sam 16:13). Also, see the En-Gedi article, “What Does the Name Jesus “Christ” Mean?“

5 Especially during this time of great oppression under the Romans, the people looked for another Moses to set them free from their oppressors.

6 See the En-Gedi article, “The Gospel as a Year of Jubilee.”

7 For more on the corruption of the Temple priesthood, see “New Light on Jesus’ Last Week.”

For more on Jesus’ understanding of the Kingdom of God, see the En-Gedi Article “The Kingdom of Heaven is Good News.”

Another excellent article about how Jews and Christians have understood messianic prophecy is by Glenn Miller.

Photos: Ali Hegazy on Unsplash, Mabdalla [Public domain], Mauricio Artieda on Unsplash

An overarching theme in both the Old and New Testaments is the idea of God becoming king over all the world. In Zechariah we read:

An overarching theme in both the Old and New Testaments is the idea of God becoming king over all the world. In Zechariah we read: We can imagine there would be much speculation about how God would establish his reign over the whole world. At the time of Jesus’ coming, this was especially important to Israel, who was under oppression by the pagan Romans. Obviously, when the Messianic King came, he would establish God’s reign by conquering the Romans. They read many prophecies about the Messiah that were images of a mighty king who defeated his foes and then took the throne. For instance:

We can imagine there would be much speculation about how God would establish his reign over the whole world. At the time of Jesus’ coming, this was especially important to Israel, who was under oppression by the pagan Romans. Obviously, when the Messianic King came, he would establish God’s reign by conquering the Romans. They read many prophecies about the Messiah that were images of a mighty king who defeated his foes and then took the throne. For instance:

God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers.

God therefore gained glory when Israel won battles against nations that worshiped false gods.1 A major theme of the Old Testament was how God was using this logic to convince Israel and all other nations that he was the supreme God. They believed that God’s intention was to enlarge his nation and to purify their hearts so that he would have a great kingdom of whole-hearted worshippers. When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4

When he told his disciples to proclaim that God’s “kingdom was at hand,” it meant that he, God’s true King had arrived on earth. Jesus’ mission was to establish and reign over God’s kingdom, and he often spoke in these terms.4