by Lois Tverberg

To modern Christians, many Old Testament laws seem arbitrary. One in particular may strike us as pointless — the commandment to wear tassels. In Numbers it says,

To modern Christians, many Old Testament laws seem arbitrary. One in particular may strike us as pointless — the commandment to wear tassels. In Numbers it says,

The LORD said to Moses, “Speak to the Israelites and say to them: `Throughout the generations to come you are to make tassels on the corners of your garments, with a blue cord on each tassel. You will have these tassels to look at and so you will remember all the commands of the LORD, that you may obey them and not prostitute yourselves by going after the lusts of your own hearts and eyes. Then you will remember to obey all my commands and will be holy to your God. I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of Egypt to be your God. I am the LORD your God.'” (Num. 15:37-41)

Many orthodox Jewish men today observe this commandment by wearing tassels (tzitzit, ZEET-zeet; plural tzitziot – zee-zee-OTE, ) affixed to a garment under their shirts, with the tassels deliberately showing so that they are obvious both to himself and those around him.

Others don’t wear them all the time, but in worship they wear a prayer shawl, a tallit, to which tzitzit are attached. Among those that do wear them, it is required that they hang outside and are not tucked in, because the scripture says that you have them “to look at.”

Not only is this odd commandment taken seriously by Jews, the text of the command is repeated at least twice daily as part of their most important prayer, the Shema. Although it may appear to us to be an act of legalism, when we dig deeper we find it has tremendous significance and a lesson for our lives today.

The Picture in the Tassels

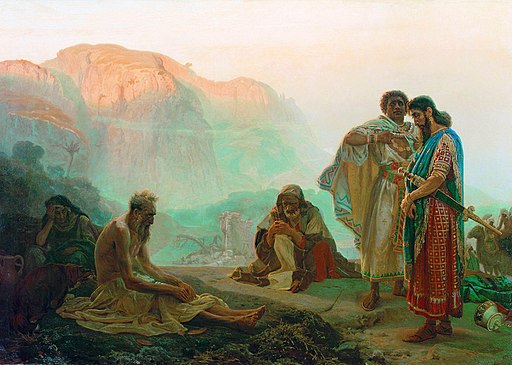

In order to make sense of this regulation, we need to see the cultural picture behind putting tzitzit on the corners of the garment. In ancient times, garments were woven and decorated to show the person’s identity and status in society. The hem and tassels of the outer robe were particularly important, with the hem being symbolic of the owner’s identity and authority.

In order to make sense of this regulation, we need to see the cultural picture behind putting tzitzit on the corners of the garment. In ancient times, garments were woven and decorated to show the person’s identity and status in society. The hem and tassels of the outer robe were particularly important, with the hem being symbolic of the owner’s identity and authority.

In the story of Saul, the cutting of the hem is a prophetic picture of God’s removing him from his reign (1 Sam 15:27, 1 Sam 24:4). In legal contracts written in clay, instead of a signature, the corner of the hem would be pressed into the clay to leave an impression.

On the hem were attached the tzitzit, which were a visual reminder of one of the most important promises that God made at Mt. Sinai:

Now then, if you will indeed obey My voice and keep My covenant, then you shall be My own possession among all the peoples, for all the earth is Mine; and you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. (Ex. 19:6)

The tzitzit communicated that idea using several cultural pictures:

- Tassels in general were a sign of nobility — in ancient times kings and princes decorated their hems with tassels. Merely by wearing tassels, the Israelites were wearing a “royal robe,” marked as God’s chosen people. In ancient times this would have been quite a statement to the nations around them who saw the regal nature of their clothing.

- The presence of a blue thread in the tassel was a reminder of the blue robes of the priests, being dyed with the same expensive dye (tekhelet) only made from one rare type of snail. It was as if each Israelite wore a little piece of the high priest’s blue robe at all times to remind them that like the priests, they were set apart for serving God. The blue dye eventually became so expensive that it was no longer required.

- The tassels were wound and knotted in a specific pattern to remind the wearer of the commandments of God. This may not have been done in the time of Jesus, but it was certainly understood in his time that the tassels were to remind a person to be continually obedient to God.

By wearing tzitzit, every Jew was reminded of his unique relationship with God and obligation to serve him. According to the Jewish scholar Jacob Milgrom,

“The tzitzit is the epitome of the democratic thrust within Judaism, which equalizes not by leveling but by elevating: all of Israel is enjoined to become a nation of priests. In antiquity, the tzitzit (and the hem) was the insignia of authority, high breeding and nobility. By adding the blue woolen cord to the tzitzit, the Torah combined nobility with priesthood: Israel is not to rule man but to serve God. Furthermore, tzitzit is not restricted to Israel’s leaders, be they kings, rabbis or scholars. It is the uniform of all Israel.”1

The Importance of the Uniform

God was giving his people a uniform to wear to show their special status as a nation of priests. God was also forcing them to be obvious about their commitment to him, because everyone around them could see their tassels too.

God was giving his people a uniform to wear to show their special status as a nation of priests. God was also forcing them to be obvious about their commitment to him, because everyone around them could see their tassels too.

God chose to make the people of Israel his representatives on earth — a kingdom of priests to the rest of the world. He wanted them to be continually reminded that he had put them on display as a light to the nations, witnesses to him to serve others.

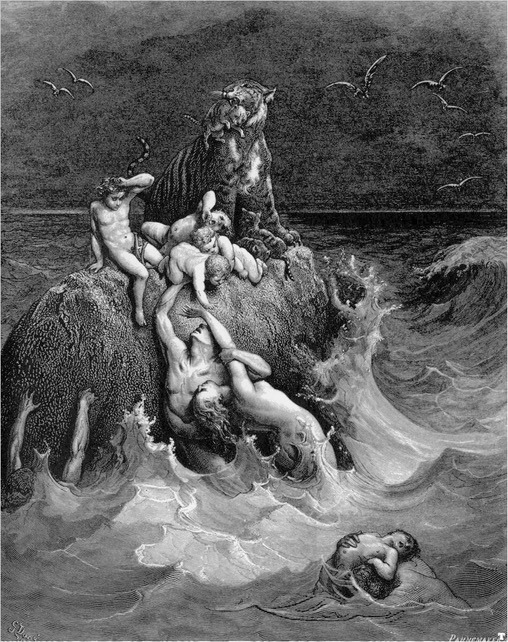

In a world where other nations prostituted themselves to idols and sacrificed their children to demons, they were to show how the true God wanted them to live. They could not blend in to the world around them, and whatever they did, good or evil, was a witness to the God they served. If they were true to their calling by being obedient to God, they would be a holy nation that the whole world would recognize.

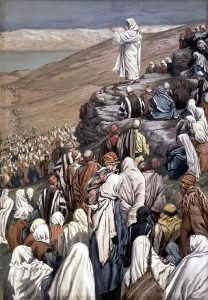

Jesus, like other Jews of the day, wore the uniform of the tzitzit. The gospels report that more than once people grasped them to be healed (Mt. 14:6, Lk 8:44). This may have come from the idea that the messiah would come with “healing in his wings” (Mal. 4:2), with “wings,” kanafim, also meaning “corners,” where the tzitzit were placed.

When Jesus criticized the religious leaders for making their tassels large (Mt 23:5), he wasn’t protesting against their wearing them. Because social status was shown through the hem and tassels, by enlarging them they were claiming honor and prestige from their piety. While they were supposed to be clear in their commitment by wearing their tassels, they weren’t supposed to use them to their own social gain.

The Challenge to Us

What importance does this have to us as Gentiles, who weren’t given this command? While the Israelites were specifically told to wear this uniform and we were not, we do share the same call as they received on Mt. Sinai. Peter says,

But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for God’s own possession, so that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who has called you out of darkness into his marvelous light. (1 Peter 2:9)

Peter is adapting God’s promise from his first covenant with the Jews and applying to it to all believers who have come into God’s new covenant, that we too are part of his holy nation and royal priesthood. By accepting this covenant, we also become God’s representatives, witnesses to the world by our actions.

Like the priests of Israel, we need to be mindful of being obedient so that we reflect God’s holiness, while serving others and bringing them closer to God. What if Christians were required to wear tzitzit? Western Christians have an extremely privatized faith, living lives like everyone around us, being glad that we don’t need to “do anything to get to heaven.”

So we are just like our neighbors, not being a judge, but also not being a light or a witness. We are hidden lamps, covered under our own bushel baskets. We focus on the minimum needed for salvation, but don’t realize that God’s goal is far beyond that.

The lesson of the tzitzit is that God’s goal for us as a kingdom of priests is to become more obvious about living our faith, enough so that others see our “tassels.” This can easily bring on accusations of being judgmental and hypocritical, so we need to rise to the challenge to go even more out of our way to be humble and kind as we live in front of others. We need to wear a little piece of the robe of our high priest, Jesus Christ. God’s goal for us is not just to “get us into heaven,” but to transform us into his representatives who reflect the love of God, and cause others to love him too.

~~~~

1 Jacob Milgrom, “The Tassel and the Tallit,” The Fourth Annual Rabbi Louis Fineberg Memorial Lecture (University of Cincinnati, 1981). (Quoted in the online article The Meaning of Tekhelet by Baruch Sterman.)

Much information on the significance of tassels for this article comes from the Jewish Publication Society Commentary on Numbers, by Jacob Milgrom, 1990. (ISBN 0-8276-0329-0), Excursus 38, p. 410 – 414. This set of Torah commentaries is an excellent resource for anyone wanting to dig deeper.

Photos: Blake Campbell on Unsplash, החבלן [CC0], Blambi at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0]